John Morra recently wrote an excellent essay examining the nature of plein air painting. I’m assigning it to all my students; it’s that good.

Most of us have been in a competitive plein air event and seen something passed off as outdoor painting that was clearly not painted from life. How do we know this? Because we were there. The atmospherics were wrong, that person was never in that spot, or—mirabile dictu—the oil paint has already set up.

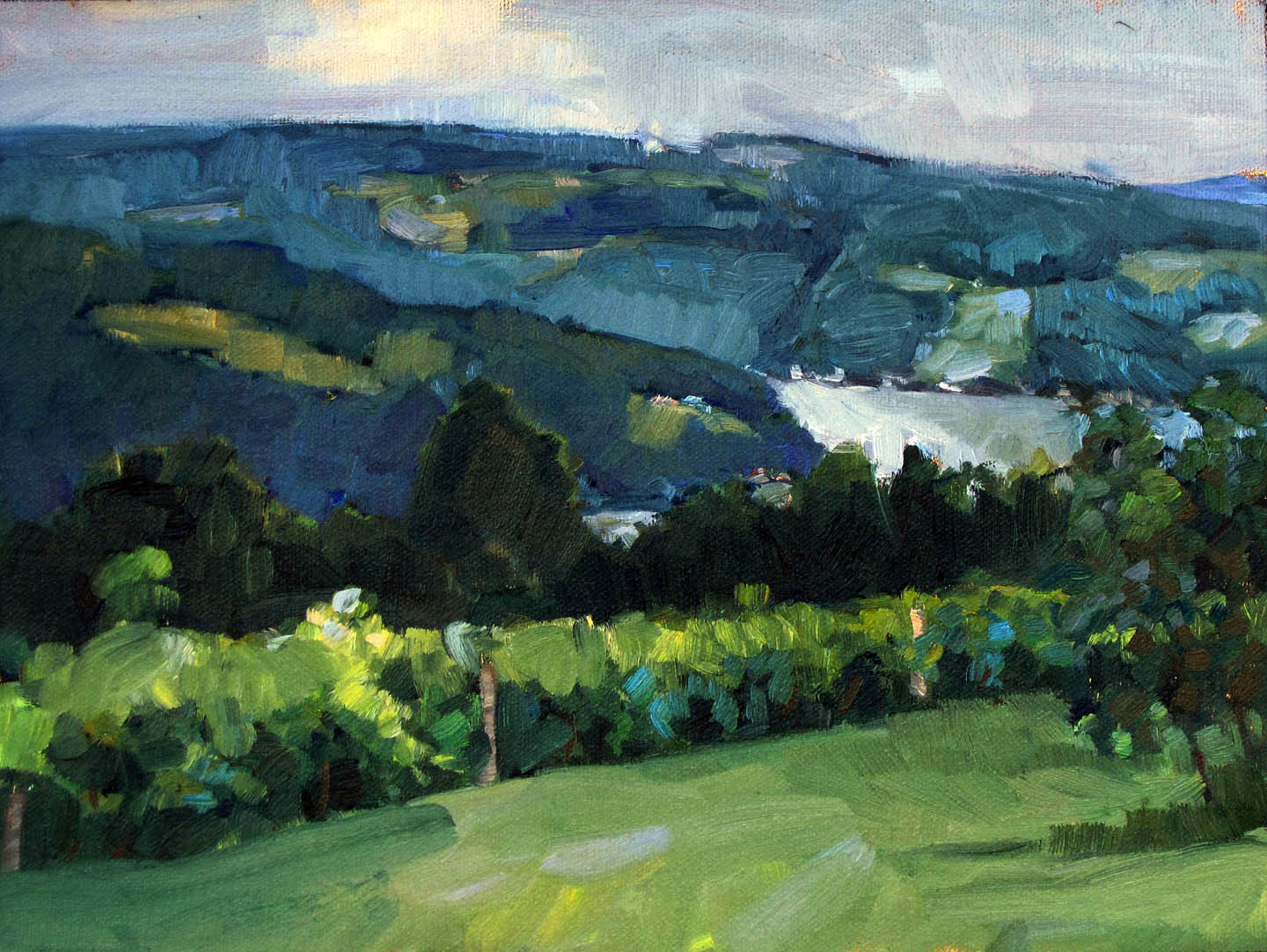

But mostly, we know because there’s a sort of static perfection to a studio painting that is never there in plein air. A painting done on site is never as balanced or stately as a studio landscape. The plein air painting expresses a longing for the natural world that just isn’t there in the studio.

Morra makes the point that we tend to over-edit in plein air painting. We’ve had two hundred years of being told that objective observation is not painterly. Until I read this, I hadn’t considered how much I’ve been programmed to think non-objectively. I came of age during the heyday of abstract-expressionism. I’m still half-apologizing for liking realism. That colors every brushstroke I make.

Still, I constantly emphasize editing in my classes and workshops. Composition is one of the hardest skills in painting. The rules of reading a composition are the same whether the piece is done in studio or in the field. We edit because we’re working around environmental distractions.

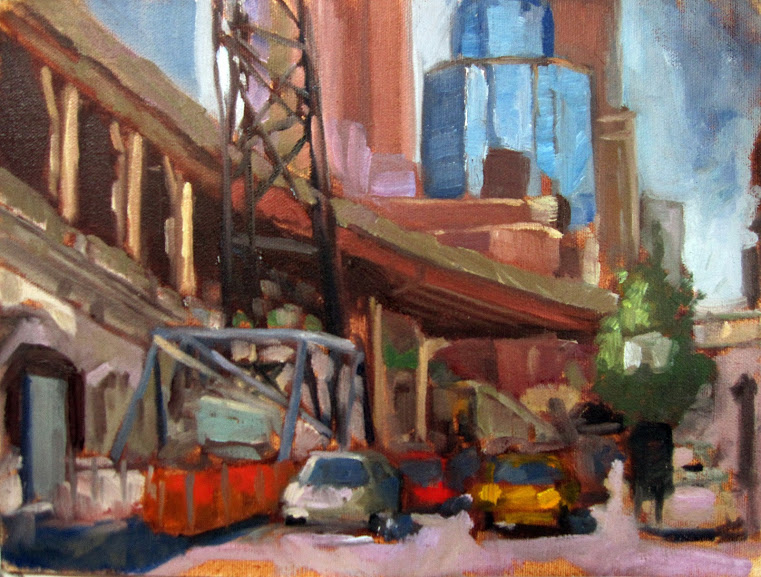

But that kind of editing can easily go overboard. Consider the lowly car. Many of us delete them—frankly, because they’re hard to paint. But today’s Toyota Corolla is really no different from Childe Hassam’s hansom cabs were in 1890. His paintings would be far weaker without them.

In fact, a lot of modern plein air is excessively planed down to a conceptual idea. We can call that style or schtick, depending on how charitable we’re feeling. Either way, too much style gets in the way of the scene. The first time I see a painter employing crepuscular rays or the silhouettes of birches or a monochrome passage in a composition, I’m dazzled. The fifth time, I realize the artist is using them for a crutch. It’s no more impressive than Thomas Kinkade’s flaming cottages.

“A plein air painting should be painted quickly,” Morra stated. This is the only point on which I disagree. Fast, expressive brushwork is the trope of our age, but it’s by no means the only way to paint. Consider the great Rackstraw Downes, for example. He paints meticulous, beautifully-drafted scenes of industrial America, and he does it observationally, working outdoors. His work is no less plein air than a fast scribble is.

Another modern painter who works meticulously is Patrick McPhee. He paints in great detail without losing luminosity or freshness. He bases his style on the first American plein air painters, the Hudson River School painters. They didn’t slap it down either.

In fact, modern plein air painting is often so fast it sacrifices drawing. A badly drawn house or person is a rookie mistake. My own preference is for fast painting paired with meticulous drawing. Want a great contemporary example? Check out Marc Grand Bois.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.