Still life occupies the lowest rung among genres, but it’s also invested with deep meaning—whether or not the artist intends it.

|

|

Roses dans un vase de verre, 1883, Édouard Manet, private collection |

|

|

Still-Life Found in the Tomb of Menna, c. 14thcentury BC, courtesy The Yorck Project |

In western art, there has always been a spoken or unspoken hierarchy of genres, with still life occupying the lowest niche. In Greco-Roman villas, ‘vulgar’ subjects like fruits and vegetables adorned walls and floors. By the Middle Ages, still life was beginning to appear as side notes in more serious paintings. The Northern Renaissance painters treated still life as its own form, with fantastical flower paintings. These pieces seem like overblown bouquets to us, but they in fact depicted flora from different countries at peak bloom. They reflected the dawning European interest in science.

|

|

Flowers in a Wooden Vessel, 1606-1607, Jan Brueghel the Elder, courtesy Kunsthistorisches Museum |

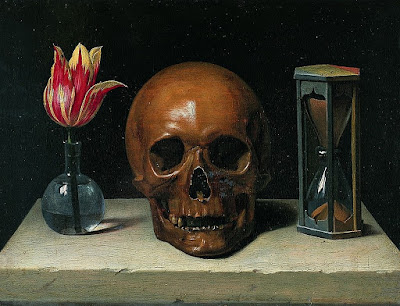

The Dutch Golden Age painters did much to improve the reputation of still life painting. Still life’s job was to reinforce social values. Vanitas painting expounds the futility of worldly pleasures. There is much overlap in symbols with memento mori, which reminds the viewer of the inevitability of death.

|

|

Vanitas with a skull, c. 1671, Philippe de Champaigne, courtesy Musée de Tessé |

Common symbols included skulls, time pieces and flowers, as in Philippe de Champaigne’s stark Vanitas, above. Rotten fruit and insects meant decay. Musical instruments told us that life is ephemeral. Fruit, flowers and butterflies spoke to the same truth. My favorite symbol is the lemon, which, like life, is beautiful to look at but bitter to the taste. (Oddly, coffee—which was brought in large scale to Europe by the Dutch East India Company—played no part in still life iconography, despite its addictive qualities.)

|

|

Take Your Choice, 1885, John F. Peto, courtesy National Gallery of Art |

Trompe-l’œil (‘deceive the eye’) has been with us as long as artists have painted, but a specific subset of it—objects on a wall or within a frame—were painted for narrative effect. Books, letters, guns, tools, dead game, playing cards and other art ‘tacked’ up on a wall were popular themes through the 19th century.

|

|

Les Anemones, c. 1900-1910 Odilon Redon, courtesy Minneapolis Institute of Art |

In the twentieth century, meaning took a radical turn. It stopped being about symbols and became about the artist’s own psyche. Odilon Redon, for example, wrote that he wanted to place “the logic of the visible at the service of the invisible.” Pablo Picasso famously said, “I paint objects as I think them, not as I see them.” Everything Picasso painted was autobiographical.

|

|

Still life, 1938, Lee Krasner, courtesy National Gallery of Australia |

From there it was a short jump to the position of the later 20th century, when meaning was banished from art entirely. It became about form and color, rather than anything the artist wanted to say.

Despite this, the artist’s own viewpoint inevitably creeps in. Édouard Manet was unfortunately afflicted with syphilis, which was in his time incurable. In his mid-forties, he developed what he thought were circulatory problems, but which was really the locomotor ataxia of end-stage syphilis. Confined to his bed, he could only paint the smallest still lives, but these are exquisite. The one at the top of this page is believed to be his last painting. Nominally a simple vase of roses, it is redolent with the grief and questioning of the end of life.