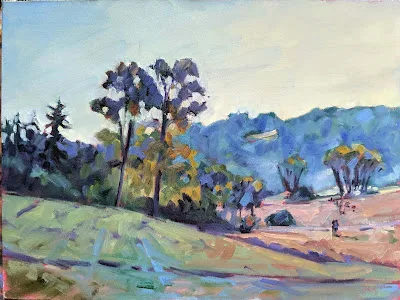

Yesterday, I ambled around the grounds of the French Legation State Historic Site in Austin musing about my plans for Sunday. The air here is clear and warm, the bluebonnets are blooming, and the trees are leafing out-perfect conditions for a day with horses.

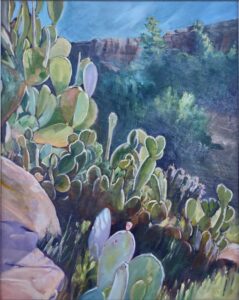

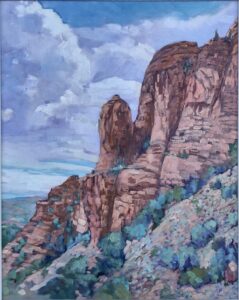

Then I remembered that my pal Sarah and the stable are back home in Maine. They’re about to receive another blast of arctic air, dropping temperatures back into the 20s and bringing more of the foul ‘mixed precipitation’ that so bedeviled last week’s workshop in Sedona. That’s my current disconnect.

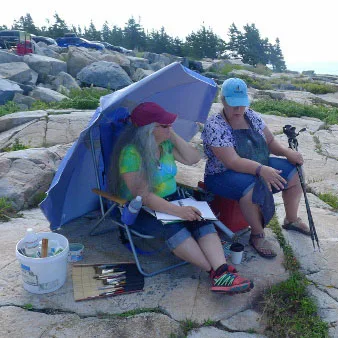

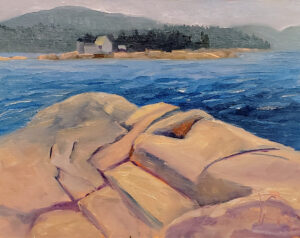

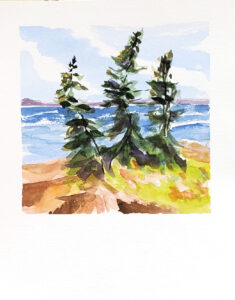

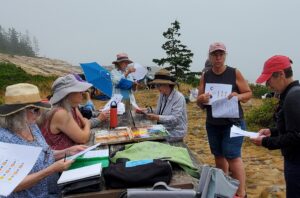

Last week’s weather was awful for plein air painting. However, I had a dedicated band that stuck it out. Nita had a pickleball fracture in her right arm. She’s a southpaw but she could only use watercolor, as managing pastels was impossible without two hands. In the cold, her injury started to throb. She painted, quietly excused herself to warm up her errant limb or go to physical therapy, and then returned. Every day.

Joan had never painted before. On my recommendation she bought a gouache kit and drove down from Seattle. No matter how grim the weather, she gamely stayed with me, exercise after exercise. At the time, I thought, “this is an awful introduction to painting; she’s never going to want to do this again.” Still, she learned the fundamentals. She says she’s going to keep with it.

What’s got you rattled?

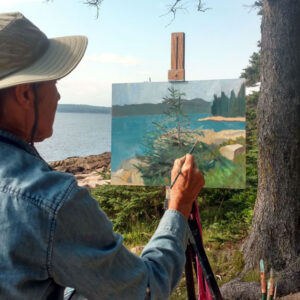

I can think of a million reasons to not paint today. In fact, I can find a million reasons to not paint every day. I’ve written before about how Ken DeWaard, Eric Jacobsen, Björn Runquist and I can dither. There are legitimate reasons why your creative impulses are blunted, including bad weather, work, children, or storms of grief or anxiety.

We all suffer from competing demands that distract us from what we need to do. For me, for years, it was my house. I couldn’t paint if it was a mess, because disorder always feels like a tide about to engulf me

Most of us have creative impulses-to write, to paint, to build furniture, to design beautiful interior spaces or gardens. The vast majority of us never do anything with those impulses, claiming a lack of time or energy. That’s despite being able to binge-watch television shows, slavishly follow the Buffalo Bills, or (in my case) read bad novels.

Are you hiding from the challenge?

Not creating is a safe position from which to operate. Your talent is inviolable, protected, a seed not open to criticism. You remain assured that you’re really a genius, which could suddenly be apparent as soon as you have the time or focus to start creating.

That gives you the latitude to criticize other creators, as you are protected from criticism yourself.

Many of us-most of us, in fact-will go to our graves never having moved past the ‘potential’ position. Those who do experience a transition to deep humility as we start to work through all the ways our craft can go wrong. We’re no longer so quick to have opinions about other work, because we recognize the struggle in which it was created.

But first you must start.

Whatever creative task you are called to do, there is always a day you must start doing it, instead of merely thinking about it. This might be that day, my friend.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

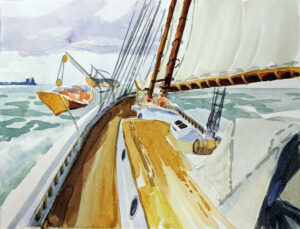

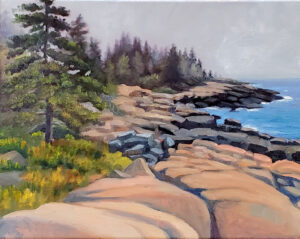

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.