First, the business

My friend Dennis used to tell me, “I’m an accountant with the soul of an artist.” That’s all very well, I’d counter, but every successful artist also needs the mind of an accountant. (Luckily, I never believed in that now-discredited left-brain, right-brain malarkey.)

On March 8-9, I’ll be presenting at the first Sedona Entrepreneurial Artist Development Program. This is open to Arizona residents aged 18 and over. The two-day intensive covers a range of topics from financial management and marketing to crafting an artist statement, developing work samples and selling artwork online. My part will be accounting for artists, and I plan to make it exciting.

Even if you hire someone to do your taxes, you still need to understand what expenses to record and what don’t matter. You need to be able to track your inventory, and, if you teach or run a gallery, how to protect yourself against liability.

Painting in Sedona

Immediately following the Entrepreneurial program, I’m offering Canyon Color for the Painter from March 10-14. There are still a few seats left.

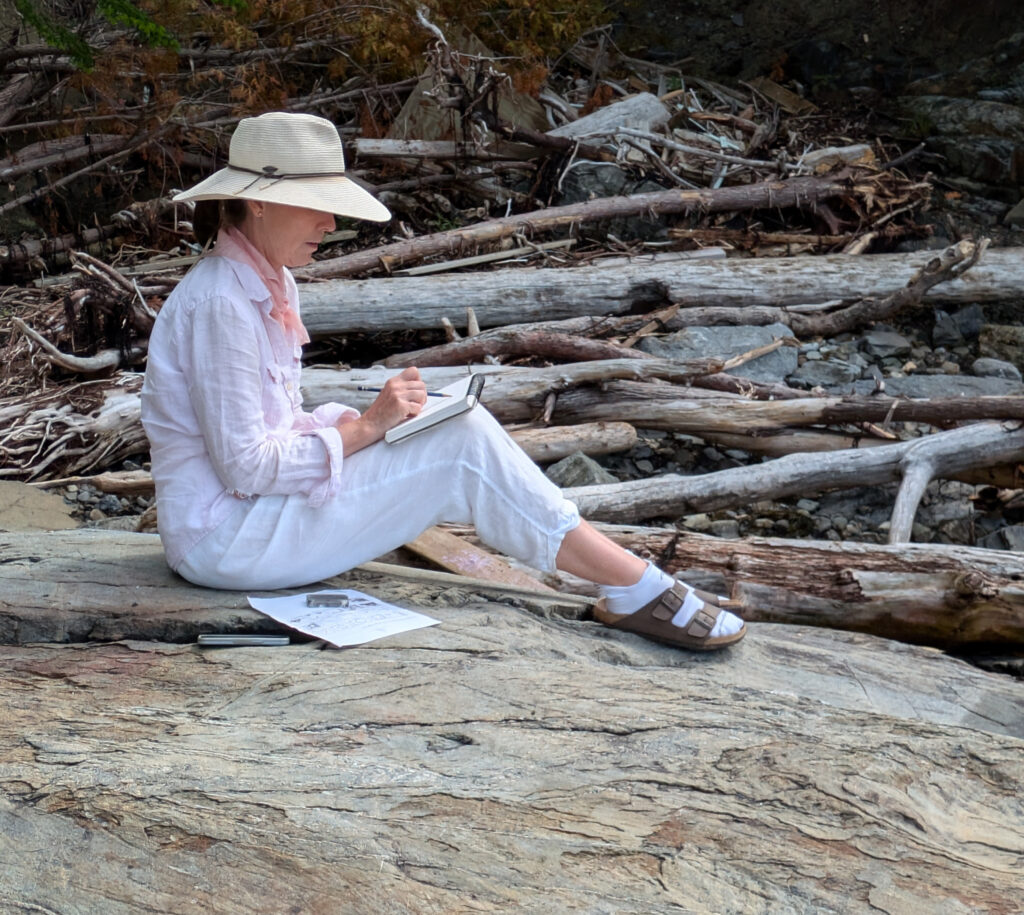

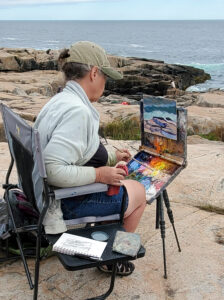

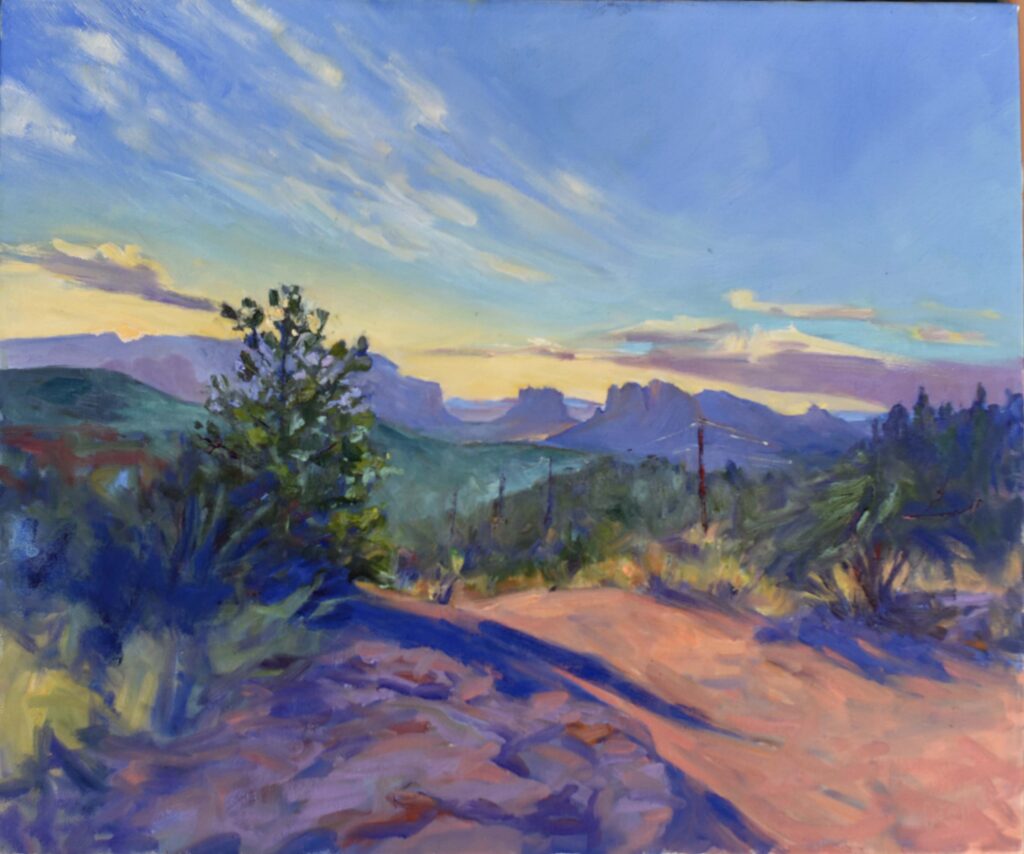

I’ve taught and painted in Sedona for several years and know great places for morning light, evening light, and all the light in between. We’ll meet on location at 9 AM, work steadily until 4, and then you’ll have the evening to hike, take one of the famous Pink Jeep tours, or try one of Sedona’s many fine restaurants. If the weather is poor—and it almost never is—we can meet in a classroom at the Sedona Arts Center (SAC).

The top five things I love about painting in Sedona

- The weather—there is a scene in PG Wodehouse’s Quick Service where the old prizefighter Steptoe is trying to convince his wife to give up on Merry Olde England. “What you want wasting your time in this darned place beats me. Nobody but stiffs for miles around. And look what happens today. You give this lawn party, and what do you get? Cloudbursts and thunderstorms. Where’s the sense in sticking around in a climate like this?”

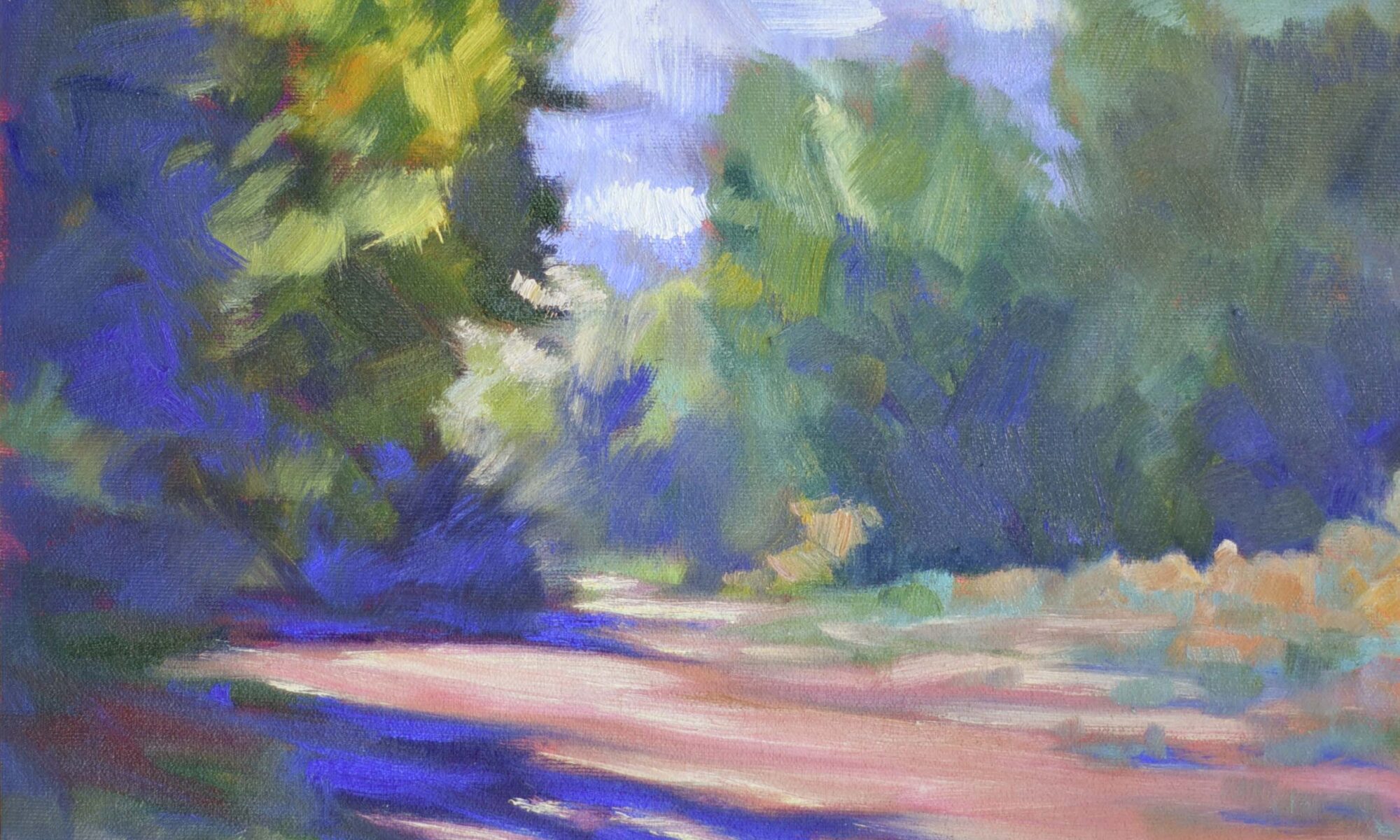

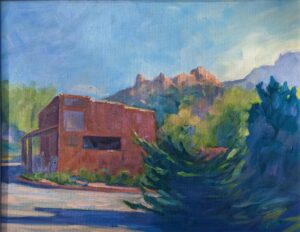

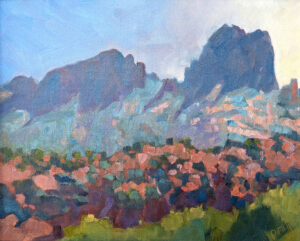

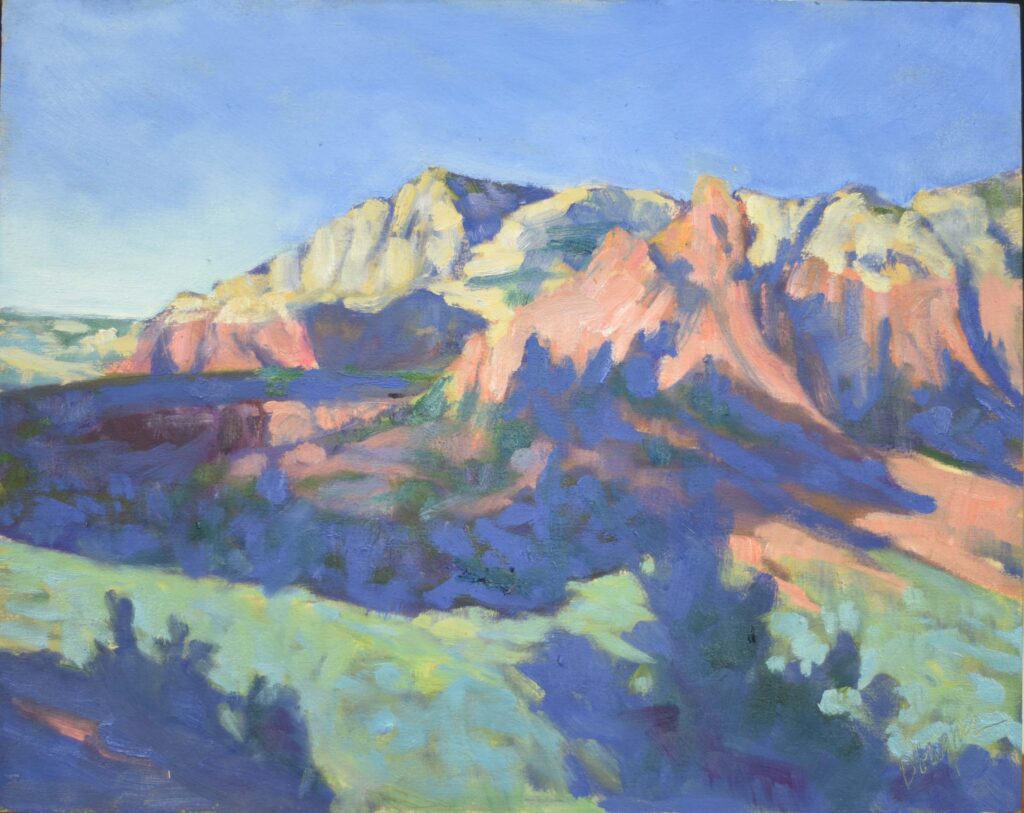

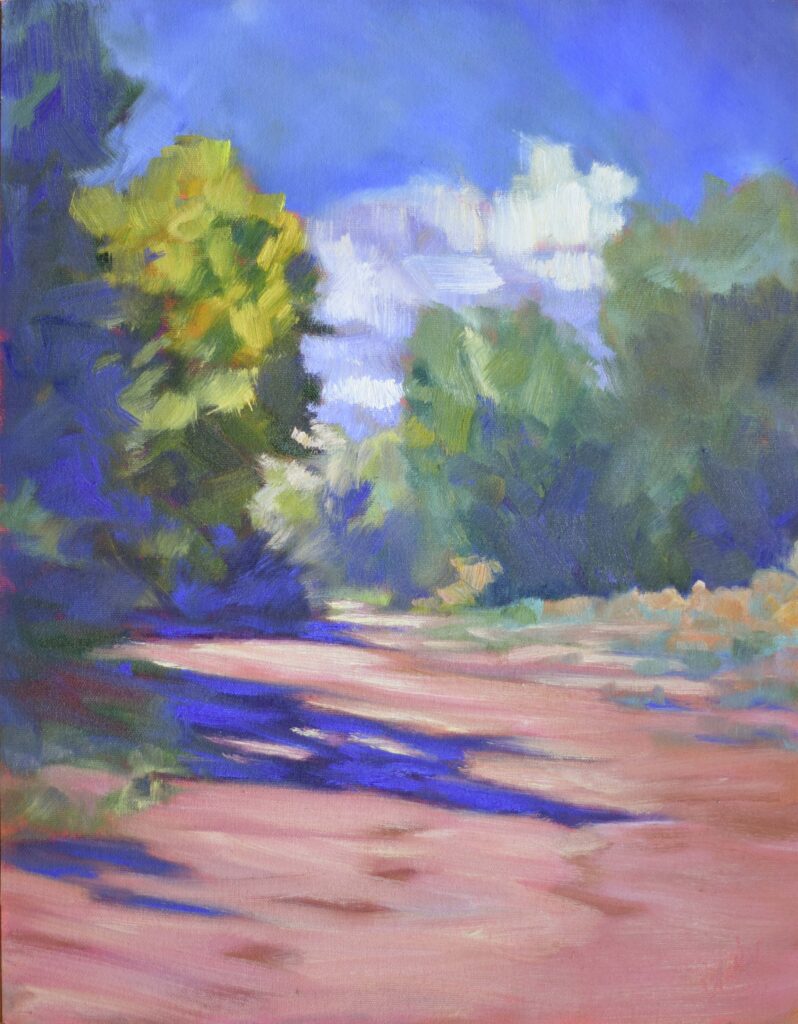

He was urging her back to California, but in Sedona it’s also almost always fine. After this winter, we deserve fine. - The scenery—Sedona combines some very brilliant colors: the reds of Bell and Cathedral Rock, the lush greens of Oak Creek Canyon, the sere yellows of the chaparral, and the deep blue of the sky. Because it’s seldom overcast, shadows jump and the light shimmers. It’s just magical.

- The people—I’ve known Julie Richard, the executive director of SAC, for a decade. It’s the same with Ed Buonvecchio, my workshop monitor. The rest of the support staff, including Bernadette Carroll and JD Jensen (with whom you’ll have the most contact), are kind and terrifically helpful.

- The hiking—There are 400 miles of hiking trails in the Red Rock Ranger District on the Coconino National Forest. Then there are state and city parks. Sedona is a hiker’s paradise, and I swear Julie Richard can tell you about every single trail.

- The funny things that always seem to happen to me there—Painting in Sedona has led to extremely funny interactions between the punters and me. I don’t think that’s from ley lines and vortexes, but because in the grand scheme of things, plein air painters are just one more dot on the overwhelming landscape. Come prepared to smile.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.