“You have a crush on every boat,” my husband once said. Of all the boats I’ve ever loved, schooner American Eagle is at the top of the list. She’s not the only windjammer I admire, or even the only windjammer I’ve painted. But I get to teach on her every year, she’s always in perfect nick and I never have to do any of the maintenance. That’s down to Captain John Foss, who restored her impeccably, and Captain Tyler King, who’s keeping up the good work.

I grew up in western New York, where my family kept a 30′ wooden sloop, first at Buffalo on Lake Erie and then at Wilson on Lake Ontario. As a kid, I figured that since the Great Lakes are smaller than the ocean, they must be safer. It’s only been since I’ve moved to the Maine coast that I’ve realized how extreme the weather in my hometown of Buffalo is. The Great Lakes are prone to unpredictable squall lines, seiches, and storm surges. Electrical storms are very common, even in winter, when they create the phenomenon known as thundersnow. Periodically, the water in Lake Ontario turns over, making a noticeable, sudden change in the temperature that results in fog. The Great Lakes have heavy freighter traffic and fog can drop in an instant. It’s less nerve-wracking now, but in my youth “onboard electronics” were limited to running lights.

On the other hand, the Great Lakes are consistently deep. If you can get out of the harbor channel without grounding yourself on last winter’s silt, you’re unlikely to hit anything submerged. That’s different from the Maine coast, where rocks stick inconveniently out of the water, or worse, not quite out of the water. When I first sailed on schooner American Eagle, I told Captain John that the thing that gave me pause about potting around in the ocean by myself is not knowing what was on the bottom. “Lobster traps, pretty much,” he laughed. And sailors today all use depth finders, which take the sport out of holing one’s hull.

However, the weather on the Maine Coast is simply not as foul as it is on Lake Ontario. (A friend who lives in Scotland tells me that Rochester is more dreich in late fall and winter than is Edinburgh.) It rains less here, and there are fewer storms.

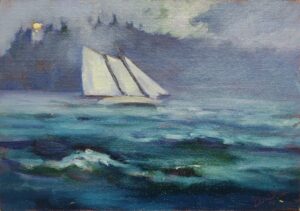

I see boats as powerful symbols of the human condition. We’re always either sailing into trouble or getting ourselves out of it. Breaking Storm, above, is about the latter, and I’ve got a painting of the windjammer Angelique on my easel that’s about the former. (Sorry about that, Captains Dennis and Candace!)

Breaking Storm is my favorite of all my schooner American Eagle paintings, but I realize it may be too large and expensive for some people. That’s why I painted American Eagle rounding Owls Head, just 6X8. It’s softer and more suggestive than the larger painting, and there’s no sense that the storm has abated.

Of course, if you sail with us in September, you can paint your own version of sailing on the Maine coast. But if you can’t go adventuring with us, a painting is every bit as wonderful.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.