“It’s going to rain in ten minutes,” I told my workshop students.

“How can you tell?”

“I feel it in my corns.”

I don’t even know what corns are, but it seemed like a nice old-timey term for a skill that’s largely lost today. In truth, I was feeling and smelling the shift in air temperature and humidity that precedes a rainstorm. Sure enough, within ten minutes, it was coming down in sheets.

It’s been a continuation of the damp weather that has wrapped the northeast in flannel all summer. My students have been remarkably good-natured despite the mizzle and occasional downpour. That’s especially true of Cassie Sano, who’s had to dry out her tent more than once.

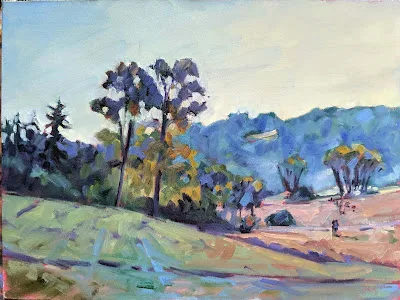

“We could paint here all week!” several people said of Hancock Shaker Village. I’d heard the same thing at Undermountain Farm. We were rained out of Wahconah Falls, but I believe it would have earned similar plaudits. Instead, we were rescued by the good people of Berkshire First Church of the Nazarene, who let us use their social hall for the day. Work continued uninterrupted.

“When the leaves turn over, and the silver undersides are showing, that’s a front change, usually not good,” I told a student from California. It’s a little like what happens when you part your hair on the wrong side; the leaves are ruffled out of their usual position. I was almost right; the weather did change. However, it wasn’t another drenching, but a clearing sky.

In the US and Canada, our weather almost always comes from the southwest. You can often tell what’s coming just by looking in that direction.

Then there’s ‘red sky at morning, sailors take warning.’ It means that a high-pressure weather system has moved east. Good weather has passed, making way for a stormy low-pressure system. The first half of that couplet, ‘red sky at night, sailors delight,’ means exactly the opposite. There’s stable air coming in from the west.

We used to have an old-fashioned ‘storm glass’ style barometer in our living room. It told us the same thing as the rhyming couplet with slightly more accuracy: falling pressure means unsettled weather is coming.

These signs were how people predicted the weather before the National Weather Service deployed legions of meteorologists and supercomputers to do it for us. For a detailed read, I find the air’s feel and smell just as reliable as my phone. That’s particularly true in coastal Maine, where the crazy-quilt coastline tosses weather patterns around like pinballs.

I spend several hours a day outdoors, in all seasons. People who live and work in climate-controlled environments never get a chance to develop that almost-intuitive sense of weather that our ancestors took for granted. They also never get a chance to see the subtle interplay of light and color that makes nature so magical.

In addition to rain, we’ve seen a lot of animals this week. At Undermountain Farm, there were horses, sheep and goats. At Hancock Shaker Village, there were cattle and a great fat pig smiling as she wallowed in mud. I patted a donkey and asked him if he knew why he had a cross on his withers; he trotted away. On Thursday, we watched a family of mallard ducks dabbling in a shallow pond at Canoe Meadows Wildlife Sanctuary, with their fat tails and feet sticking straight up in the air. We couldn’t help but laugh.

And all too soon, it’s over. Today’s our last day, and then we’re gone for another year. But we’ll be back; the Berkshires are magical.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.