It’s possible that I have too many travel watercolor kits. They include two Winsor & Newton field boxes (cute and cuter) as well as a beautiful antique box that was a gift from my friend Toby. The trouble with prefabricated kits is that they have unnecessary pigments and usually leave out the good stuff. Nobody needs convenience mixes like Sap Green or Payne’s Grey—having them on your palette just results in duller colors.

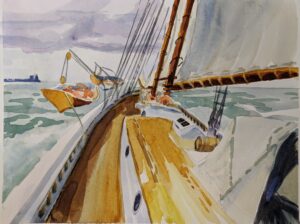

That’s why I make a custom one for students of my watercolor workshop aboard the schooner American Eagle. Of course I have one of those boxes, too.

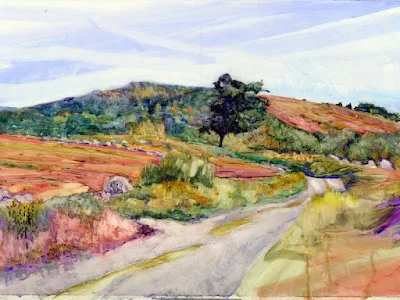

Then there’s my kit for bigger watercolor paintings, which is what I recommend to my plein air students. I have used this 18-well palette successfully for field paintings of up to 36” wide, although I do have to clean it off frequently. Again, it holds more paint than is strictly necessary, since nobody needs 18 different pigments. What’s most useful is a bigger mixing well, and sometimes a disposable plate is just the answer.

Choosing the right travel watercolor kit is always a complicated dance between what is optimal and what I can pack or carry.

I’m hiking in Yorkshire this week, after which I will go up to Scotland. For painting, I’ve limited myself to what I can carry in what the British call a bumbag (because ‘fanny pack’ would be an obscenity over here). I wanted a kit for myself and for my pal Martha, who’s hiking with me.

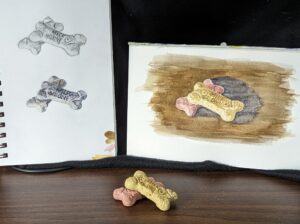

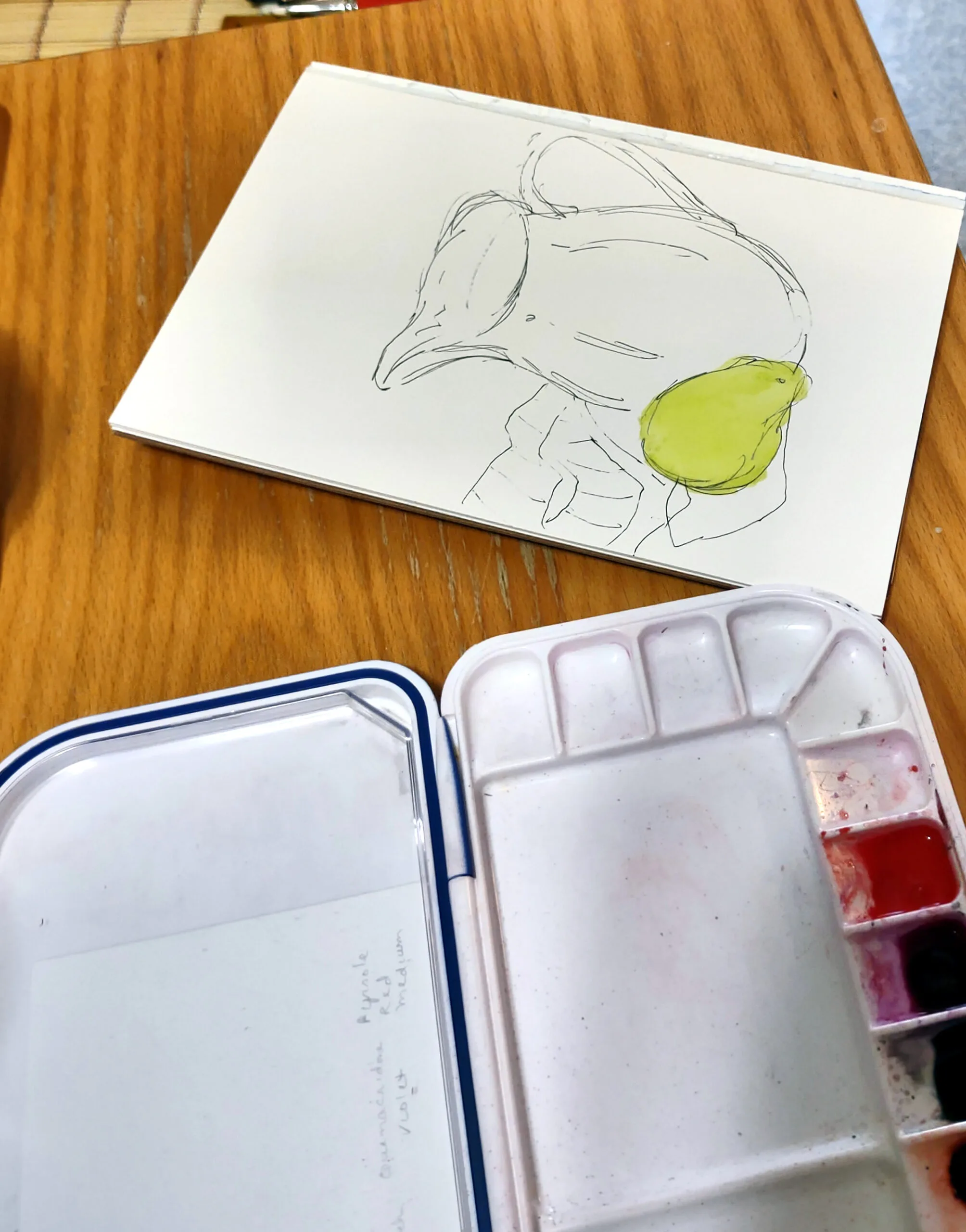

I started with an Altoids box, because where I live it’s cheaper to buy Altoids than an empty tin. I stuck down four half pans with double-sided tape. Why four, when limited palette in watercolor only needs three paints? I didn’t want to leave a gap next to my mixing well.

I used three primary colors made by QoR. I’m a big fan of these paints, which are made by Golden Artist Colors in upstate New York. They’re bright, clear, and reasonably priced, and they’re tuned to the American palette. To get the broadest range of color, I used:

I filled the last pot with white gouache just for fun.

QoR makes nice field kits, including this one, which has the virtue of not including extraneous pigments. But in addition to wanting to carry as little as possible, I want Martha to have as little choice as possible. Too much choice can drive a new painter nuts.

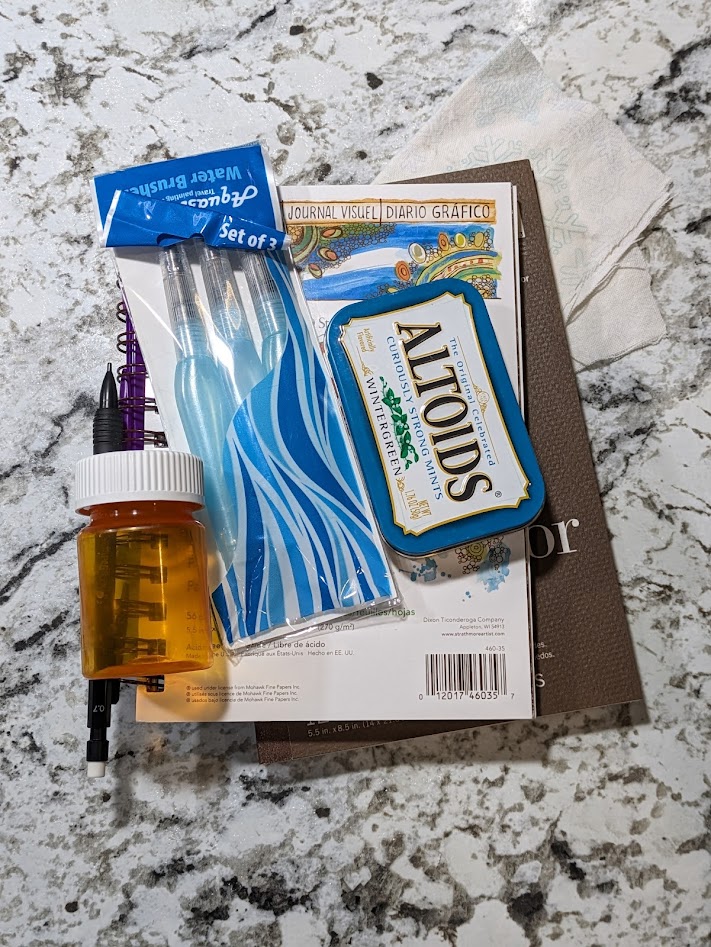

There are some lovely folding brushes out there, including this nifty travel kit. That was a bit pricey for a gift, so I got each of us a set of Pentel water brushes. I added a Strathmore multimedia visual journal and a bound Strathmore watercolor pad, two mechanical pencils, a pill bottle (for water) and a small flannel rag. Now we each have a kit we can carry and use as the spirit moves us.

Have you ever made a travel watercolor kit for backpacking? If so, how did you do it?

I’m in Britain on another lovely, long, blister-inducing hike. I’ve turned my phone off and while I’m gone, Laura will be running the office. Just email me as usual if you have questions or problems registering for a class or workshop. (Who am I kidding? She fixes all that stuff anyway.)

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.