On Monday, I posted Let’s Paint Some Duds! After about the hundredth person told me they have no trouble whatsoever painting duds, I realized my hook was lousy. It tapped into fear of failure instead of challenging people to be more questing and adventuresome.

I’ve had many emerging artists tell me that half or more of their paintings are duds. That’s shocking; it’s way too high a failure rate, especially when it comes in the learning phase. For that matter, there are other painters who fail just as often but don’t even realize it. (And far be it from me to wreck their happy illusions.)

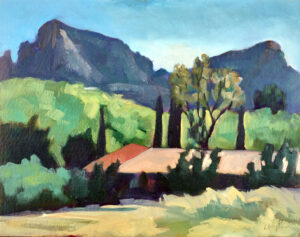

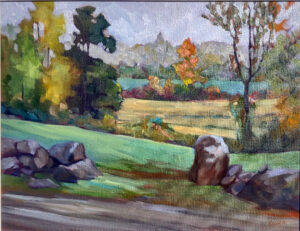

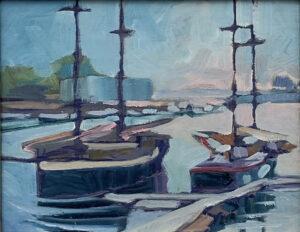

Duds are a particular problem in plein air painting, so much so that my pal Brad Marshall coined a term for the process of making them: flailing around.

Why so many?

I also get frequent emails and texts that read, “I’m stuck! What’s going wrong here?” That’s why I periodically teach an online critique class; you’ll advance more quickly when you can answer that question for yourself.

But the answer almost always comes down to bad composition. Either the darks are not organized, or the focal points are not clear, or there’s not a clear and compelling armature. Figuring that out in advance, with a value drawing or notan, saves tons of time and effort.

Composition organizes the design elements of a painting. It provides structure and balance, guides the viewer’s eye, and determines where a painting falls on the all-important scale of harmony-to-tension. Composition controls the visual appeal of a painting, but it also controls its emotional power.

A weak composition is still a composition.

The same student who kvetches about flailing and failing often resists the idea of studying formal composition. “I want to be spontaneous and natural,” he will say. Well, composition, like puberty, is going to happen whether you take a hand in guiding it or not.

Weak compositions impede the very message that the supposedly-spontaneous artist wants to convey. Conversely, strong compositions guide viewers through the content. By strategically placing focal points, controlling movement, and using visual cues, you influence not just what your viewers see, but what they think and feel. And isn’t that the point of communication?

Then there’s the question of balance and emphasis. Just as the cannonades in Tchaikovsky‘s 1812 Overture are carefully placed to emphasize the point of Russia’s victory over the French, your focal points must fall in sweet spots. They must be reinforced with contrast and line. When it works flawlessly, we see a painting that is beautiful individual, and stylish-without overburdening our minds too much about how it happened.

How do I learn to be a better composer?

I’ve written extensively on this blog on the subject of composition, which of course you can access for free. Above all, there’s my cardinal rule of painting: don’t be boring. I can’t restate that often enough.

If you really want to give up flailing and failing, I invite you to also take my online course, The Correct Composition, which I just released on Friday. Give yourself a lot of time to do the exercises and take the quizzes; you’ll get far more out of it than you will by just skimming the videos.

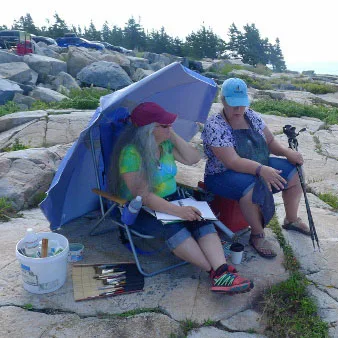

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.