Whenever I sail into Bucks Harbor in Brooksville, ME, I tell my students about Robert McCloskey‘s One Morning in Maine, which was set there. McCloskey has had an inordinate influence on me. As a kid, my husband looked and acted like the eponymous hero of Homer Price, my first and favorite chapter-book. It took me decades to realize I’d married my childhood crush.

I’ve pored over every detail of McCloskey’s books, because every object is a fascinating window into an America that was fading when I was a child and is largely gone today.

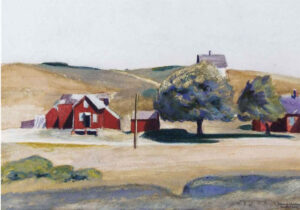

I recently spent some time considering Edward Hopper‘s Truro, Massachusetts paintings. He and his wife Jo had a summer house there, and he spent at least four months a year in Truro from 1930 to his death in 1967. While I respect his urban scenes as revolutionary, challenging and dramatic, it’s the Truro paintings I gravitate to. They are prosaic country scenes-barn, church, farmhouse, post office-but with brilliant composition and elegiac light. They are so universal in design that they could have been painted in almost any part of the United States, but the overarching theme is early 20th century America.

I have a similar response to Hopper’s Rooms for Tourists, above. It’s a quintessential Maine boarding house, except that it was really in Provincetown, Massachusetts. Not that it really matters; boarding houses were once common in New England and New York. In fact, I romanticize them. I think I might run one someday, until I remember that I don’t much like changing beds and I hate to cook.

I posited to my aforementioned husband that my love of the countryside and Maine in particular was probably shaped by paintings like these. “I think most of us were shaped by television,” he replied, and he’s probably right, except that I grew up without it. Anyways, I never see people seeking out Gilligan’s Island or The Brady Bunch, but I sure know a lot of folks who are jazzed by old gas stations, tourist cabins, farms and lighthouses.

Mythmaking is as old as art itself, but in America it can be laid at the feet of the Hudson River School painters, who used the Romantic idea of sublimity to say that the American landscape, with its patches of agriculture juxtaposed with nature was the very reflection of God himself. It’s at least one of the roots of the idea of American Exceptionalism.

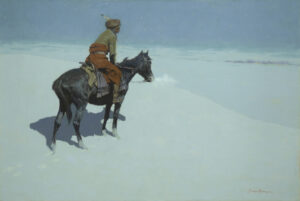

They were, of course, painting a landscape that was fast disappearing. Artists have always been drawn to that which is either gone or going. That make sense when you think of how difficult we find the world in which we live. Perhaps in fifty years, people will find fields of solar panels or modern windmills beautiful, but right now they make us uncomfortable. That nostalgic kick is part of the enduring charm of the two older Wyeths, Frederic Remington and Norman Rockwell, among many others, but their work was actually nostalgic right from the start.

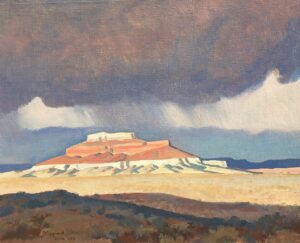

I think of the places I like the most, like the Great White North, and how I saw it first through the eyes of the Group of Seven and Rockwell Kent. I love farm country, especially the Midwest as seen by Grant Wood, and the West as seen by Edgar Payne or Maynard Dixon. Artists are above all mythmakers, and I am just beginning to understand how deeply they’ve influenced my goals, dreams and sense of place.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.