It has always baffled me that an art historian is required to learn German, French, or Italian but not to study religious history. Religious paintings comprise the bulk of art through the ages, from the shamanistic cave art of paleolithic man right up to the 18th century. That’s not just true for Christendom, but for every culture worldwide. Art is a primary way people have explored the meaning of their existence, and that is the fundamental question of religion.

I can only speak for my own culture, but my own grounding in Christianity makes reading western paintings easy. I do not need stories and symbols explained to me; even deeply buried allegorical references make sense without a lot of clarification.

(That’s also true, by the way, for paintings based on Greco-Roman myth, because we learned those stories in school. Today I wonder why they spent so much time on them, but apparently there was a lot more time in the school day back before STEM. Peter Paul Rubens had it right when he painted those fat gods and goddesses as cartoon characters.)

I’ve often wondered how students of art history read the symbols in religious art when they don’t have a grounding in the thinking underlying them. Art historians are famous for their capacity to pontificate. In the post-church era, how can their students discern what in all that blather is reasonable and what is nonsense?

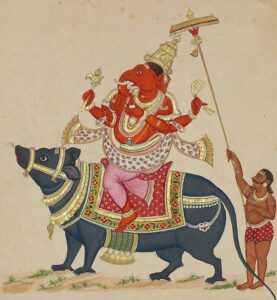

Go back in time with me to my first visit to the Rubin Museum of Himalayan and central Asian art. Tibetan art is overwhelmingly religious and conservative and, I suspect, cautionary. The Tārās are, like the Greco-Roman gods, partly personifications, or representations of abstract ideas in the form of personages. Looking at the work totally divorced from its religious underpinnings, all I saw were five floors of ferocious figurines.

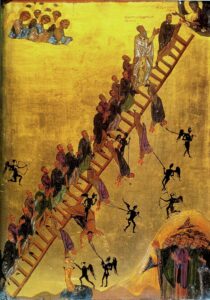

I suppose my response was like a non-Christian’s reading of a crucifixion painting. They can be frightening, especially in a culture as divorced from death as we are. However, crucifixion was an historical reality running from pre-Roman times to the modern world (it’s still a rare but legal form of punishment in parts of the world). To the Christian, the crucifixion of Jesus represents the absolute low point of the story, but it also points to the ultimate redemption of humanity.

My art-historian goddaughter was raised in a traditional Chinese household, so Tibetan house shrines don’t seem that strange to her. She was able to explain the rough outlines of the Tārā permutations to me. I still wouldn’t want any of it in my house, but, then again, I wouldn’t want The Martyrdom of Saint Erasmus by Dieric Bouts in my house, either.

I’m not an art historian, just a simple painter who loves paintings. And I think it’s important that I understand those works from the viewpoint of the artist. So when I read Breaking a taboo: religion is being invited into three major museums, my first reaction was, “it’s about time.” Art should never have been divorced from its cultural underpinnings in the first place. Its absence reflects a longstanding, anti-religious bias on the part of academia.

We’ve had a century or more of sneering at religion and the faithful. Are there any art historians left who are qualified to interpret art in the language and culture in which it was made? Where’s Sister Wendy when we need her?

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.