On Monday and Tuesday, I wrapped up a session of painting classes. I sighed and said, “First I taught you to paint and draw realistically, and now I’m going to teach you to paint and draw non-realistically.”

To the non-artist, this makes no sense. Why go through the laborious business of learning to draw and paint accurately, to then cut out so much of what you just learned? The first step is the journeyman’s and the second step is the master’s.

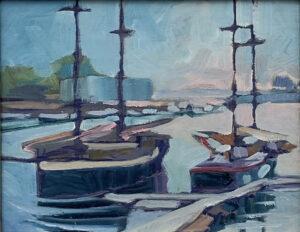

There is no such thing as absolute realism in painting. Every style, even the most detailed, is a simplification and abstraction of reality. Even hyperrealism is a kind of abstracted and stylized view of the world. Where you eventually land on the continuum between hyperrealism and pure abstraction is ultimately up to you.

But to have complete control over visual representation in art, you must first understand and masterfully replicate reality. Realism is the starting point from which we launch ourselves into an infinite number of artistic styles.

Sometimes people misunderstand abstraction

Ironically, right after class was finished, I had a brief discussion with Bruce McMillan about a painting he did of two pears tossed in the snow. “Many viewers dismiss abstract artists as lacking the skills of ‘accomplished’ artists,” he mused. “They think we can’t paint reality. I sometimes pause to paint something realistic to remind myself and viewers that painters simply paint.”

In truth, it takes great skill to pare something down to its essentials. I was reminded of this while looking at some devastatingly simple monotypes by Marc Hanson.

But first, realism

The midcentury abstract-expressionist masters were well-trained draftsmen. Their style intentionally moved away from traditional figurative work. They focused on expressing emotion and the act of painting itself with large, gestural brushstrokes and spontaneous technique.

Learning to draw realistically, even if you plan to be an abstract artist, is valuable because it provides a foundation in form, perspective, anatomy, and the nuances of light and shadow. This grounding allows you to manipulate and distort these elements when creating abstract compositions. Knowing the rules lets you break them.

Realism gives you a visual vocabulary, along with compositional awareness. But once you’re there, then what?

What’s your style?

“I want to develop my style” is one of the most common things people say to me, and ironically one of the least important. We all have a nascent style from the first time we pick up a pencil. Our mature style is what’s left when all our errors are stripped away, but in some ways that’s a controlled manipulation. We distort and simplify things in our worldview. To do so intentionally takes practice.

The worst thing you can do is chase someone else’s style. There are things you can learn from other artists, things you can control, errors you can overcome, but ultimately, your voice is yours alone.

Here’s where we jump off the diving board:

As I told someone today, I never thought being an artist was about inventory control. I think these numbers are right.

Zoom Class: Beyond realism to expressive painting—four seats left

Tuesdays, 6 PM – 9 PM EST

February 18, 25

March 4, 18, 25

April 1

This class focuses on design and composition for expressive painting. Students will be encouraged to develop their own personal creative vision while working on refining their artistic skills through traditional studies.

This class is targeted toward more advanced painters who’ve already mastered the basics of paint application. It’s open to students in watercolor, gouache, oils, and pastel. Learn More

Zoom class: design and drawing—three seats left

Mondays, 6 PM – 9 PM EST

February 17, 24,

March 3,

March 17, 24, 31

This class improves on the skills learned in Fundamentals of Drawing. We’ll use a pencil but all of these concepts are transferrable to painting; experienced painters are encouraged to try them in paint as well.

This class is targeted to the learner who has mastered measurement, shading, and perspective and wants to further develop skills in design and rendering. Learn More

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

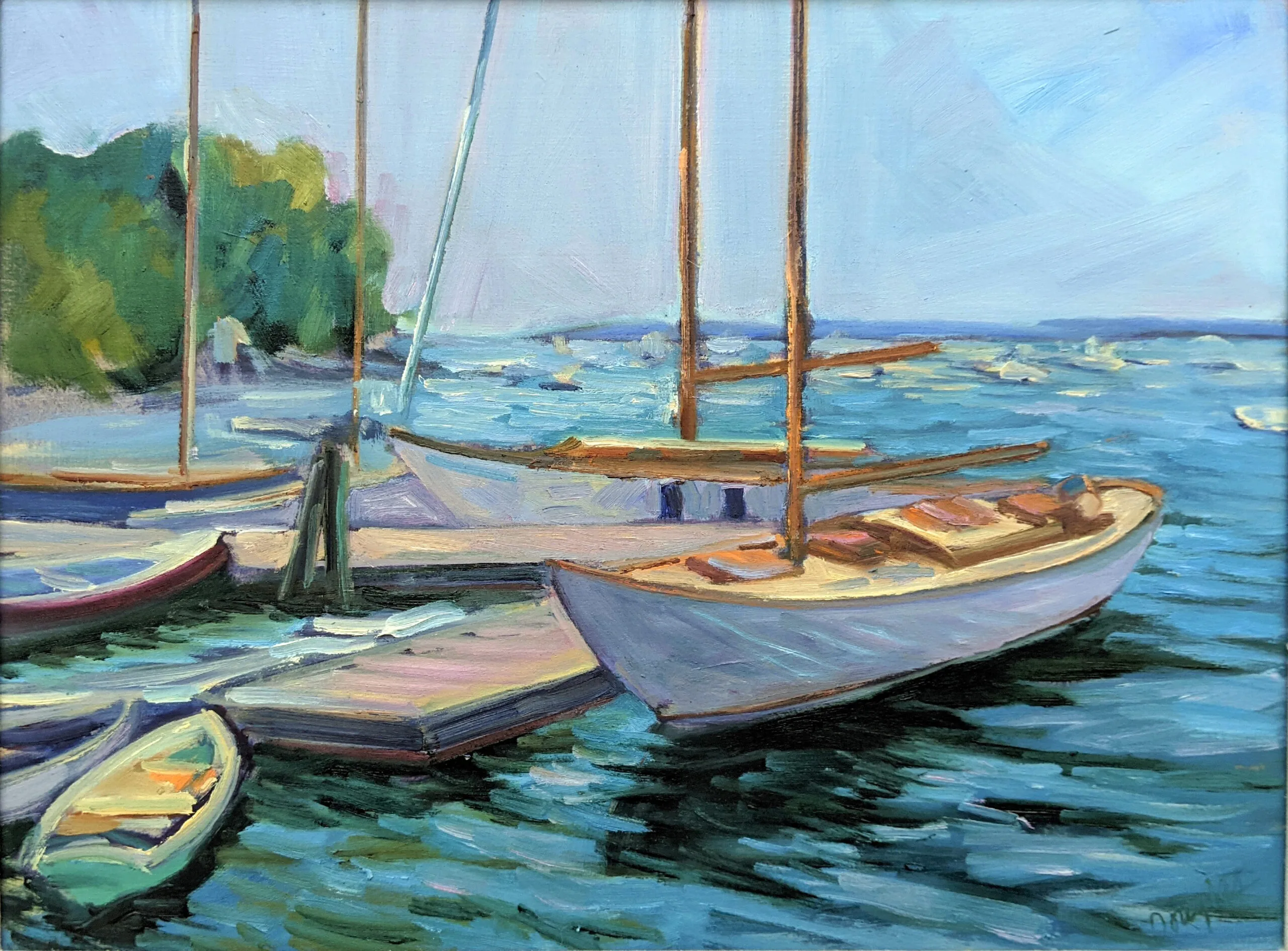

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

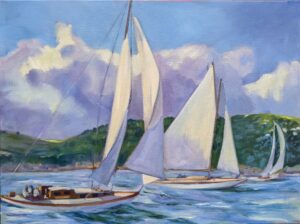

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.