“It’s supposed to snow in Sedona at 8 PM,” my husband told me as I was driving west on 89A yesterday evening.

“That’s funny, because it’s squalling right now,” I answered. Before I made it back to my digs in Cornville, I had two weather alerts on my phone. Since I’m driving a very tiny Mitsubishi Mirage, I was concerned about being blown off the road or, worse, floating away.

I’m a worrywart. Of course, nothing happened.

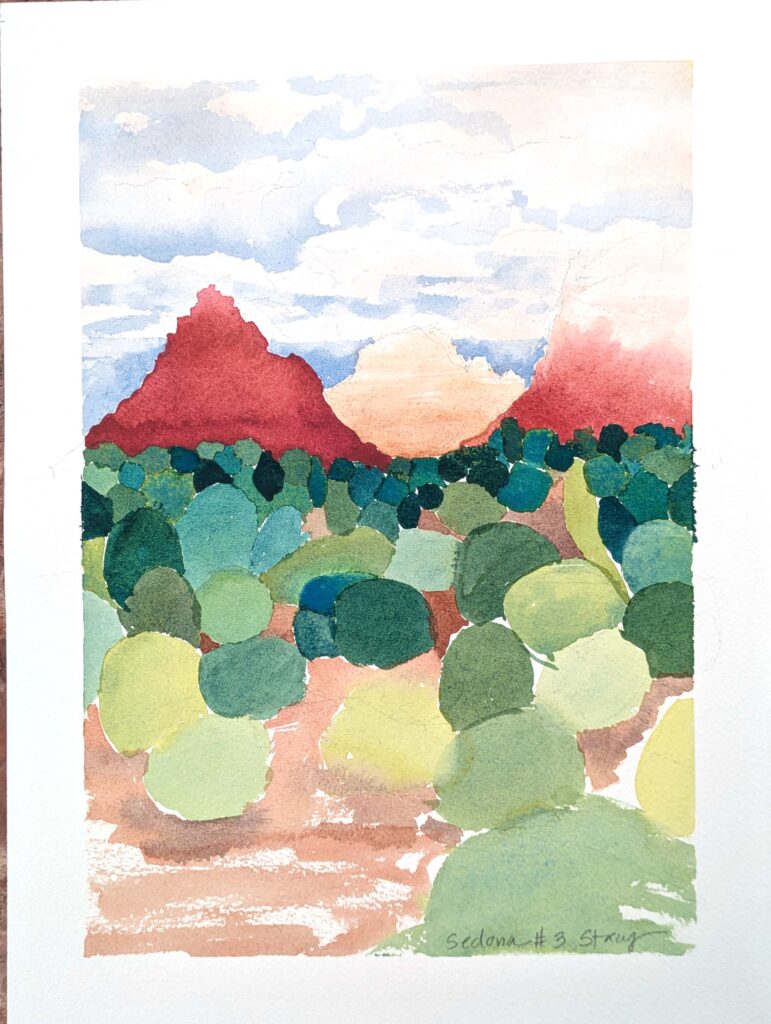

There’s something wrong about snow in palm trees or cactuses, but Sedona and environs have been in a moisture deficit all winter. I feel badly for my students, who wanted to paint outdoors all week, but we had three good days in lovely weather. I’m also happy that we were able to break Sedona’s drought for them.

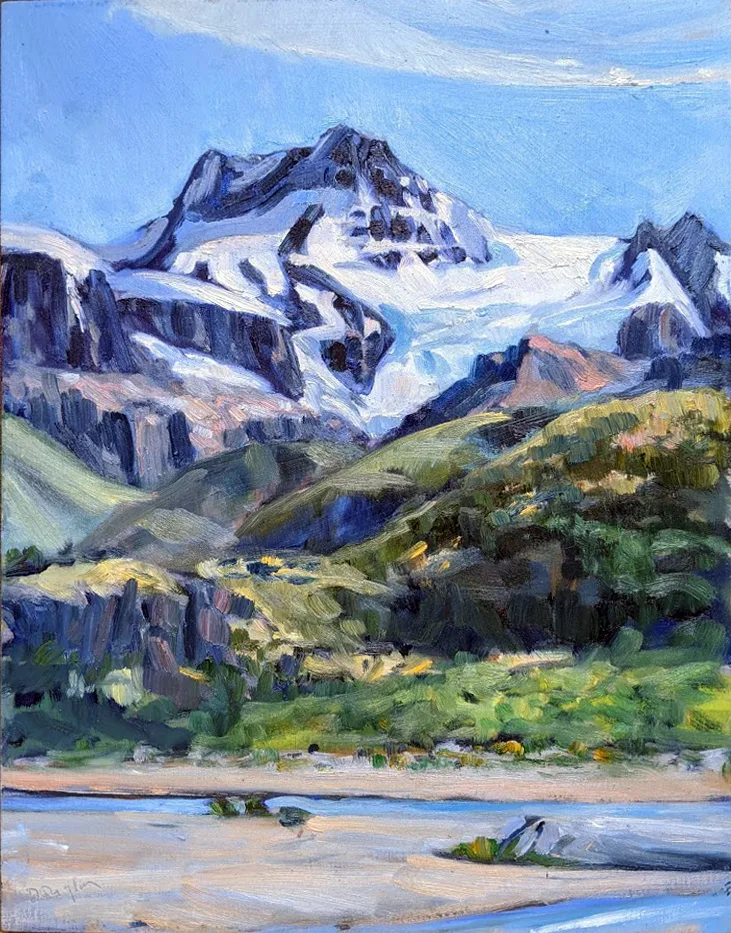

Plein air painting means expecting the unexpected, and that’s as true of workshops as it is of events. And, of course, we’re all learning, including me.

Snowing in Sedona

I have never taught a painting workshop where I haven’t learned something from my students. This week, it was about using apps like Grid Maker, GridMyPic, etc. that allow you to paste grids directly over photographs in my phone. That means I never have to ruin another value sketch by gridding across it in my sketchbook. Who knew?

I teach several painting workshops a year, and I hope that I send my students away with a variety of technical skills, including painting techniques, drawing and compositional fundamentals, and a healthy dollop of color theory. Then there are the practical skills, including material mastery, like brushes, surfaces and mediums. There are strategies for faster setup, better decision-making, and getting the best results in the fastest time. And everyone faces the same painting challenges, like dealing with slow drying in bad weather or accelerated drying in hot weather—both of which we’ve faced this week.

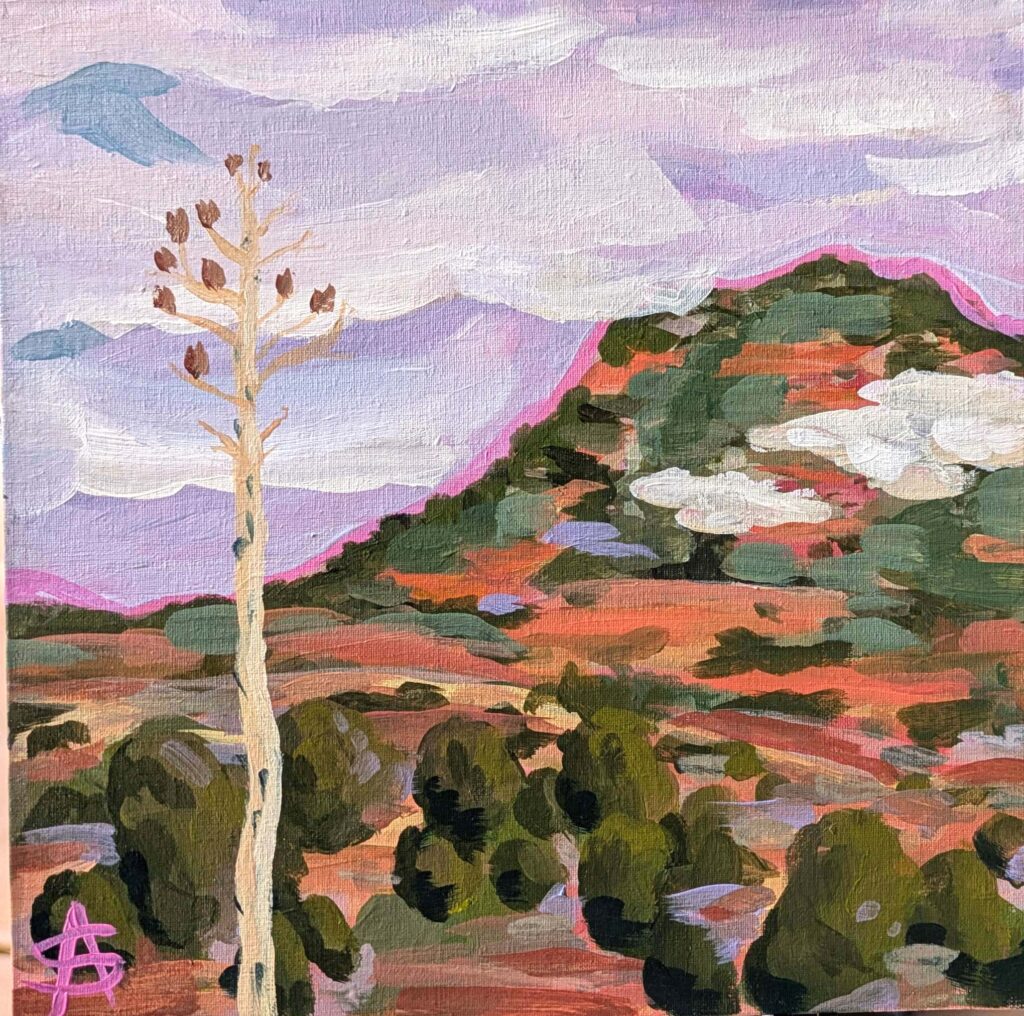

But what a painting workshop really offers is a change in mindset. If I’ve done my job right, I’ve sparked new ideas and helped build connections between people who’ve never met before. I’m very tired, but it’s a good tired, because I’ve had a great group of students this week.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.