One of the questions I’m asked most frequently is, how can I sell my art? The answer is different for each person, but it always requires a shift in outlook. We artists create work that’s specifically from our mindset. However, selling art is no different from any other sales. It’s not about us, but about the customer.

Sales is about showing how our product effectively addresses our customer’s needs. It means building a relationship with the customer and addressing his or her concerns. That two-way communication may be transient or evolve over a long period of time.

Your customer may want to beautify a space, prove something to himself or others, engage with the artwork on an intellectual level, or even just match his wallpaper. All are perfectly valid reasons to buy a painting.

Do you have a strong, consistent body of work?

Your work should be constantly evolving; if not, you’re probably just parodying yourself. Still, you should have a strong, consistent line of development. Somewhere online you should have a portfolio showcasing your best work. This presence needn’t be elaborate or expensive; a free blog host might be sufficient if you’re just starting out. It shouldn’t be scattershot—nobody wants to see your poetry, hand-embroidery, pottery and recipes if you’re trying to sell paintings.

Your website should have a reasonably complete bio and you should have a brief artist’s statement available. You will be asked for it.

Selling in bricks and mortar galleries and stores

Are galleries dead? Certainly not, although they’ve drifted sideways in the past few years. I particularly like well-run cooperative galleries.

The day of cold-calling with a portfolio under your arm is (thank goodness) over. Start by thoroughly researching the gallery’s current exhibitions and artists, including visiting if possible. The gallery’s website may have explicit application instructions, which simplify matters. If not, prepare a cover letter, an artist statement, and a portfolio (with links to the work online and to your social media), and send them by email. If you don’t hear back, follow up by phone after a reasonable time has elapsed.

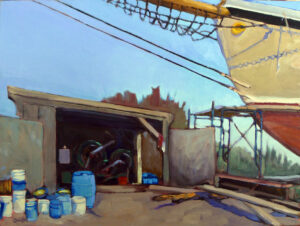

But coffee shops, restaurants, and offices may actually sell more work, and often charge no commission at all. Besides my own gallery, I have work in a dental office and a realtor’s office; the realtor has used my work to stage property. The more my work is seen, the higher my profile.

Selling online

If I were starting today, I’d use FASO; Eric Jacobsen, Poppy Balser, and many of my other friends are on it. It’s commerce-enabled and will scale up as you grow. I have known artists who’ve auctioned their work on eBay, but I think that needs a high profile to start with.

Social Media

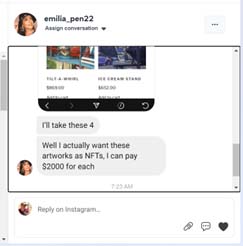

Regardless of how you plan to sell, you’ll need to make a truce with social media. I like LinkedIn and Instagram best right now, followed by Facebook, but I do post on all available social media several times a week.

This is a constantly-shifting landscape, so keep your options open. My student and friend Cheryl Shanahan is fantastic at witty reels, and I want to be more like her. Since we’re apparently keeping TikTok, it’s time to loosen up that part of my brain.

Art fairs

I’ve done art fairs from St. Louis, MO to New York City. They’re a lot of work setting up and tearing down, so I’ve aged out of them. Their great advantage is that once you’ve paid the booth fee (which can be steep) the profits are all yours.

If you do them, diversify your merchandise. For painters, that means offering prints of your work along with originals. Many people attending these events don’t really want to spend $2000 on original art, but they will spring for a nice print.

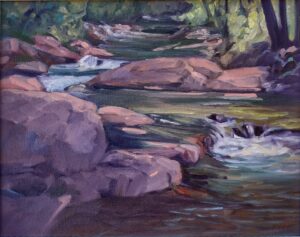

(I’m thinking about these things because I leave on Friday to present at the Sedona Entrepreneurial Artist Development Program. After that, I’m teaching a workshop, below. There are still some openings, if you’d like to join me.)

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

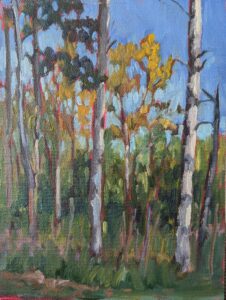

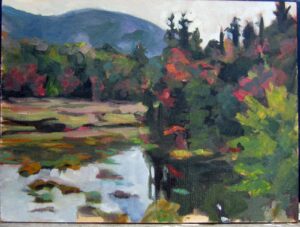

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.