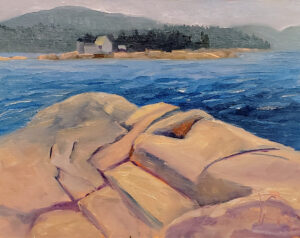

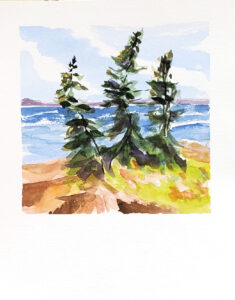

Acadia had nearly 38,000 fewer visits this June than it did last year, but you’d never know that from the crowds at Schoodic Point. I’d intended to bring my class elsewhere, but the winds on Tuesday produced big rollers crashing across the rocky promontory. That’s a special experience, and I wanted my students to have the opportunity to paint them.

Apparently, John Q. Public also likes the drama of big seas, and he came along as well, bringing everyone he knew with him. They came in their hundreds and their thousands, and they kept standing in my view. The nerve.

Life in a National Park has its comic moments. Walking across the parking lot, I heard a cranky gentleman remonstrate to his wife, “There’s nothing here but water!”

It also has its terrifying moments. Waves crashing against big rocks can be killers. I hate watching people skirting the edges of the rocks in blithe disregard of the danger, especially with their children in tow. On Monday, I saw a woman heading down the slope in her bikini. Since I didn’t read about her in the Bangor Daily News, I presume she was warned off.

And there are sublime moments. For much of the day yesterday, a big fat seal cavorted in the surf, entertaining the crowds.

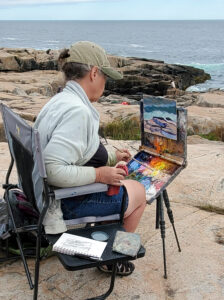

Painting in public can be a wonderful experience, a way to express yourself and share your art with others. But when you’re trying to get something done, it can be irritating.

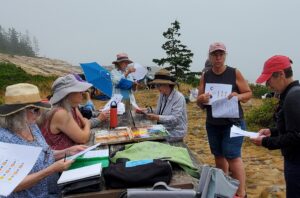

The best defense is a good location, but there are few of those on the open rocks of Schoodic Point. Karen managed to set up with her back to a ledge of rock. That protected her from the problem another student was having. “They stand behind me, breathing loudly,” she said. That’s a slight improvement over the people who stand behind you making unsolicited comments.

My personal bête noire is the person who stands behind me saying, “that looks like so much fun!” Done right, painting is darn hard work, but we do it because the payoff is so great.

One could set clear boundaries with body language, but that’s hard to maintain when you’re concentrating. One student mused that she’s going to put a sign up that reads, “Artist at work: approach with credit cards.” Of course, they could wear earbuds, but then they couldn’t hear me.

Another technique would be a debris field. I, like many artists, am particularly good at dropping things. If I’d stop picking them up, after a few hours, I’d have a dangerous physical barrier between me and the public.

I once knew an artist who had a large QR code on his paint box. When people spoke to him, he just waved his brush irritably at the code.

But I think the best technique is polite deflection. My monitor, Jennifer, has some rehearsed phrases, like, “this is a class. Our teacher, Carol Douglas, is over there.” Sometimes she even points in my general direction.

For the poor schmoes in my class, I can only suggest, “I’m really focused on this painting right now, but I appreciate your interest,” or “I’d love to chat later when I’m on a break.”

“See that woman over there?” She’s our teacher, and if I don’t finish this quickly, she’ll hit me with her stick,” however, is completely over the top.

My new class, The Essential Grisaille, is available now.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.