I’m not certain who among my students at Sea & Sky at Schoodic first suggested the twenty-strokes challenge, but it was so much fun that I asked my students at my Berkshires workshop to do the same thing. If you’ve never done it, it’s a great exercise for controlling the noodling that sometimes ruins a promising start. The only rule is that you do a painting in twenty strokes or less.

We all concentrated on making every shape count, including using a larger, well-loaded brush and filling in all the continuous areas in one shot. I was able to lay out the painting below in four carefully-considered strokes. The rest was just details. (Sadly, I didn’t photograph it before I added some extra emphasis brush strokes.)

This was also an exercise to demonstrate that a centered composition is not inherently bad; it’s what you do with the rest of the space that counts. Centered compositions in themselves are imposing and serene. For proof that they work, see King Tut’s funerary mask or Arkhip Kuindzhi’s imposing Russian landscapes.

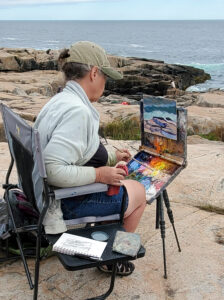

Before we did that fast-painting exercise, we went out to Schoodic Point to paint the sunset. None of us were counting strokes, but the sun dropping behind a mountain moves very fast. I doubt there are many more strokes in this than the prescribed twenty.

I took it home to my studio intending to finish it, but there is nothing I can do to improve on what’s there. It says everything one needs to say about the sun setting over Cadillac Mountain without a single extraneous brushstroke. Anything I add would diminish it.

How much is that painting worth, anyway?

Sometimes I am asked why a Cy Twombly scribble is worth $70 million. The high-end art market is complicated, being composed of talent, money laundering, speculation, rarity and social cache (and I have no opinion about the value of each).

The same question might be asked about why this painting is worth the same amount as Lacecap Hydrangea and Daylilies, which is the same size and a lot more complex. It’s not about how much I struggled to paint it (and the flower one was a terrific struggle), but about all the knowledge I brought into the painting.

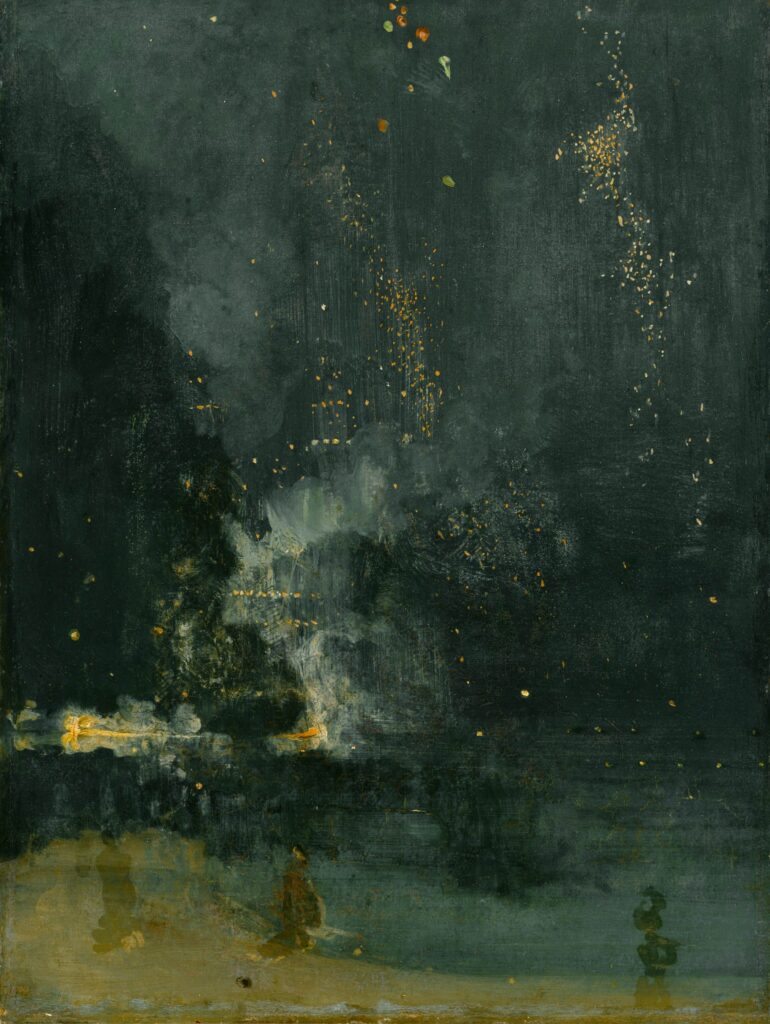

James McNeil Whistler was panned by the legendary art critic John Ruskin, who by 1877 was no longer up to the challenge of modernity. Ruskin wrote, “I have seen and heard much of cockney impudence before now, but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.”

Whistler sued. He did not ask 200 guineas for two days’ work, he argued; he asked it for the knowledge he had gained in the work of a lifetime. He won, although he received only a pitiable farthing in damages. The case bankrupted Whistler and probably accelerated Ruskin’s mental decline. However, time has vindicated Whistler.

Art is not judged by the effort that goes into a particular piece, but by whether it ploughs new ground, challenges ideas, is technically skilled and provokes a response.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.