When Antiques Roadshow was all the rage, didn’t you ever wonder what you’d do if you found an Albrecht Dürer woodcut in your attic? I regretfully concluded that I’d have to sell it. However, I do have lots of original art in my home, made by contemporary artists I respect.

Dürer’s woodcuts were originally intended for middle-class people like me. Time, scarcity, and the murky movements of the international art market have rendered them impossibly valuable.

Reader Sandy Sibley sent me this interesting video, by someone calling himself People’s Republic of Art (PRA). In places it’s naïve; for example, there have been celebrity art ateliers churning out work since the Renaissance. But overall, it’s an accurate picture of the current forces shaping the global art market.

That’s huge: $65.1 billion US in 2021. Most of that money is not making its way into the pockets of working artists. It’s spent on commodified art. That means either old masterworks that have become stratospherically valuable, or new art by celebrity artists.

This world of art money-laundering or buying shares in art assets has nothing to do with us working artists. We’re out here in the hinterlands beavering away, and the fat cats are in New York and London moving massive amounts of dollars. The two worlds never meet.

How that affects you

However, PRA also talks about a shift in how art is appreciated. That does affect us. Art museums have gone from being a collection of individual works to be admired in their own right, to being a stage-set for social media. That in turn is changing how art is made.

We’ve all seen images of people taking selfies with great paintings, or the scrum in front of the Mona Lisa. I’ve experienced something related, being used as the backdrop of tourists’ selfies.

But PRA’s talking about creating art that’s designed upfront to produce great profile pictures for the wanna-be influencers of this world. Art made for selfies is a real thing. Galleries and museums are as driven by ROI as the rest of us, as I wrote recently, so they give the people what they want.

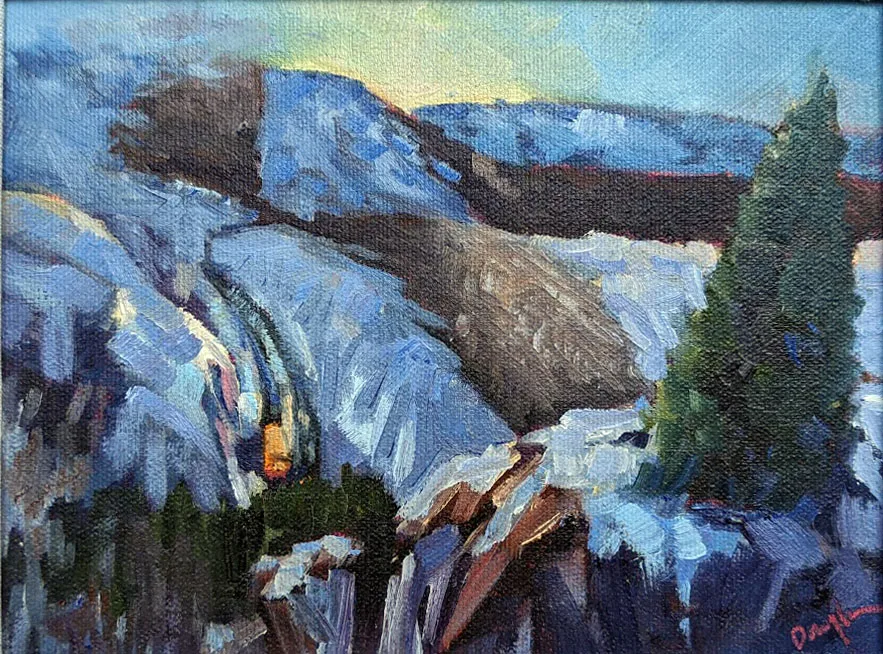

That affects everyone in the food chain, including us. I’ve dabbled with florescent paint, tiny lightbulbs, and backlighting my substrate. Ultimately, I’m drawn back to just painting. It’s a devilishly difficult puzzle. Nobody who truly engages with it can ever feel like they’ve achieved total mastery.

The fundamentals remain

Long before there was a stock exchange, people were drawn to art to surround themselves with beautiful and edifying things. That impulse is deep in the human soul. It remains with us even after we’ve gone home from the Immersive Van Gogh, and hopefully even after we turn off the television.

My young friends are collecting posters and curios just as we were at their age. But PRA raises a good point: instead of decorating your room with posters of famous art that sold for millions, buy original art that moves you.

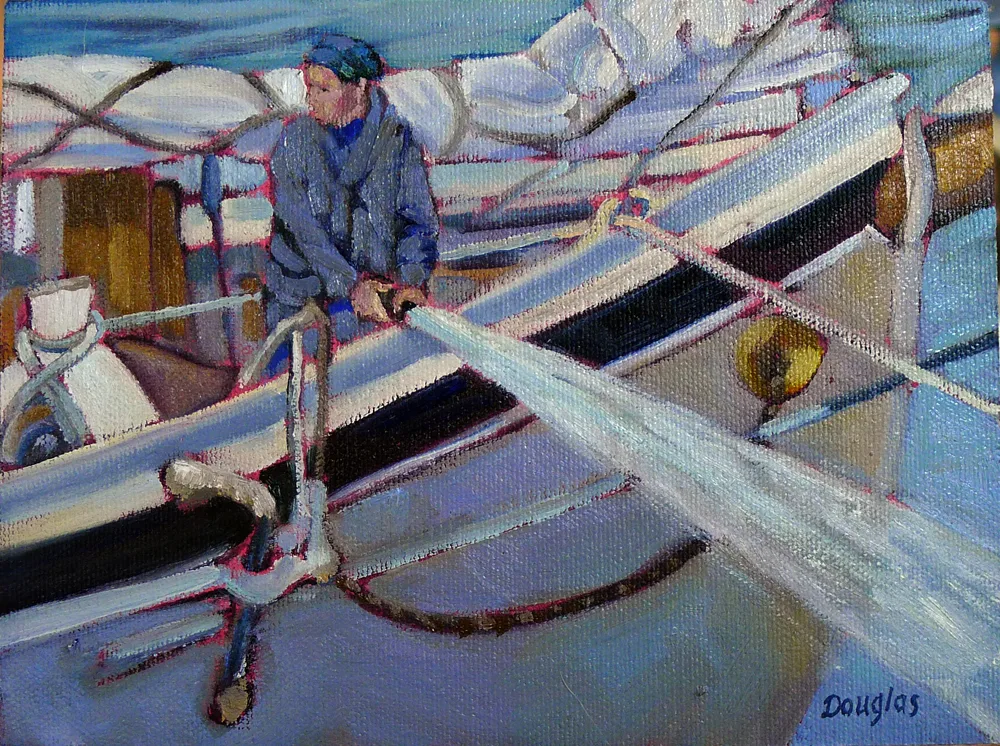

The difference between $200 and $800 may seem enormous when you’re thirty years old, but real art has levels of meaning and experience that its mass-produced analogs can never provide. There’s the search, when you visited galleries and art shows and thought about what the paintings meant and how well they would stand up over time. There’s the craftsmanship, which will throw up detail and meaning to you for years to come. There’s identification with a real person: the creator. And if chosen well, that real painting will have value long beyond when the print is consigned to the dustbin-just as that Dürer woodcut does today.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.