On Wednesday I wrote that NFTs were the logical descendants of conceptual art. Reader Pam Otis responded by asking, “What kind of return on investment do museums get from owning/showing works like that? How much does having a certain piece drive traffic through their doors or attract benefactors with deep pockets?” It’s a great question, because that’s what makes a pile of candy on the floor worth $7.7 million.

What is ROI?

Return on Investment (ROI) is the value of an investment versus its cost. Every person makes ROI calculations constantly. “Is it worth my time to put the Christmas decorations away, or should I make some frozen meals for next week?” is an ROI calculation.

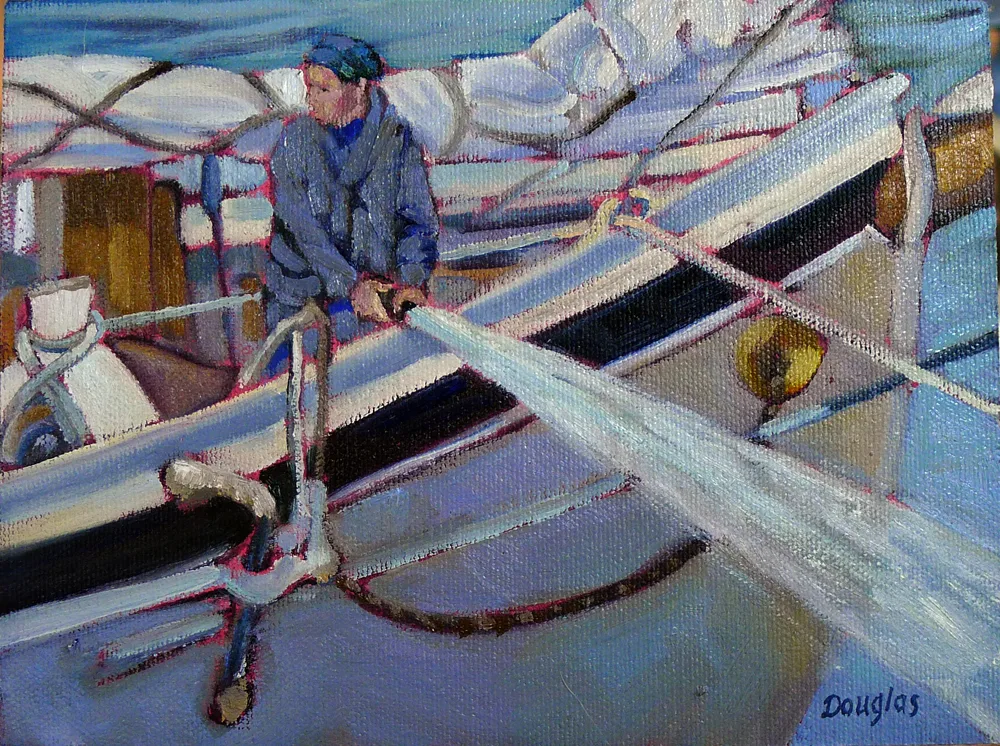

ROI is why my friend Ken DeWaard doesn’t paint plein air on cloudy days; those paintings are hard for him to sell. It’s why commercial galleries don’t carry work their clients won’t be interested in, as worthy as that work might be. Museums may think of themselves as educational institutions, but they give us blockbuster shows of Van Goghs, Sargents, and Sorollas to bring in the punters.

Treading a fine line

It’s easy to get too focused on money and only produce work that buyers will love. That’s how artists end up being parodies of themselves, churning out variations of the same tired theme. There’s also the opposite tendency, to make omphalocentric work with a complete disdain for the market.

Vincent Van Gogh is often cited as an example of an artist who produced brilliant work without thinking about selling. That’s not true; his brother (who supported him) was an art dealer. His correspondence shows that he did have an eye to the main chance, and only his early death prevented him from being a commercial success in his own lifetime.

Professional artists must tread a fine line between being true to our inner vision and being comprehensible. “Give me something I can hold on to,” I told a very talented student who resisted that idea. She thought I was asking her to sell out; I wanted her to help me find a way to understand her work.

Selling out

The phrase sell out, meaning to prostitute one’s ideals, dates from 1888. It probably arose with 19th century socialism and utopianism, which presented the idea of markets as evil. That idea of not selling out is sadly pervasive today.

We can think of the marketplace as the other half of a conversation we started by creating art. The market tells us things about our work. Sometimes they’re things we don’t want to hear. If instead of getting mad, we listen, we can learn a lot.

That can be very tough when one’s ego is on the line. Do I really have the emotional courage to look at the work that got in a show when mine was rejected and figure out why?

It sometimes seems that the art market is irrational. For example, jurors and buyers respond emotionally to subject matter. While their response is subjective, that they do it is a fact. Knowing it helps you develop strategies to succeed.

When our work doesn’t sell, it means one of two things:

- It isn’t different, meaningful, or beautiful enough to engage buyers;

- It isn’t properly marketed.

It’s up to us to figure out which, and then to do something about it.

Speaking of marketing

On Monday I start teaching a six-week session on Atmospherics. You didn’t hear about it because it was sold out before it was advertised. I’ve got only six workshops scheduled for 2023, and that’s all the live, in-person teaching I’ll be doing this year. (The rest will be by video and Zoom.) If you want to take a live class from me, hie on over to my website and sign up! When they’re gone, they’re gone.