The Torah describes Bezalel and his assistant, Aholiab, as having decorated the Tabernacle sometime between 1400 and 500 BCE. Polygnotus of Thasos, who worked in the mid-5th century BC, was a superstar in ancient Greece, as was his student Pheidias.

All of the original work of these men is now lost; we know nothing about it except copies and descriptions.

Before them, art was anonymous, but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t made. Before homo sapiens were in Europe, their Neanderthal cousins were making art on the Iberian Peninsula. Prehistoric cave art is a human universal, found worldwide. Why?

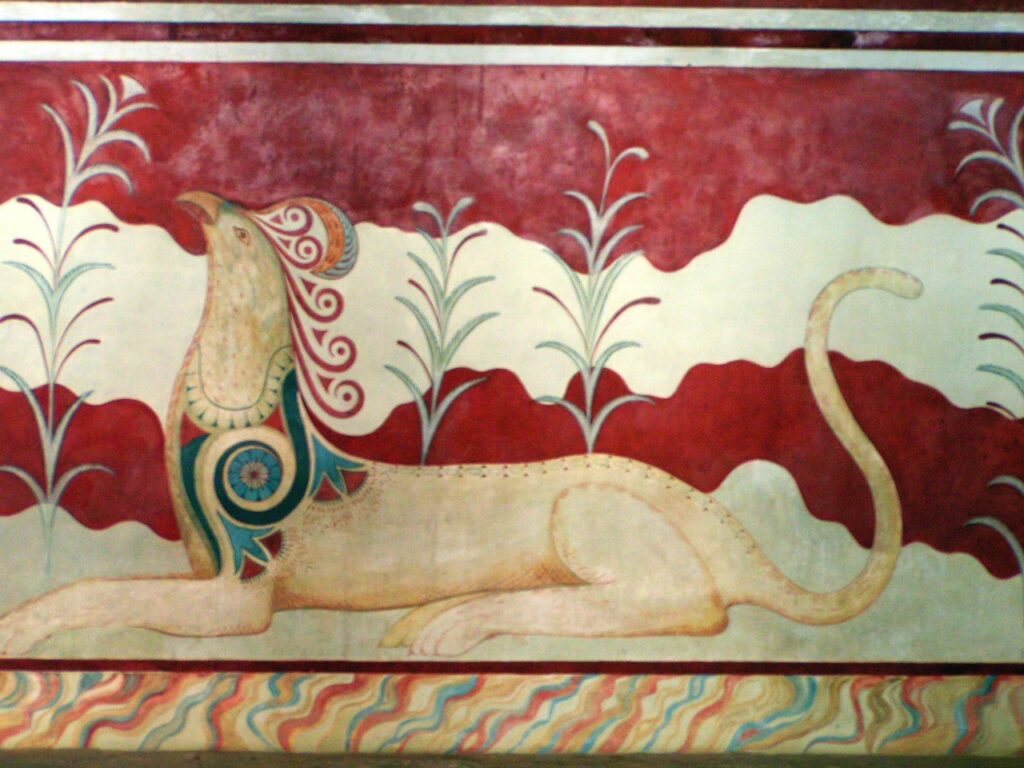

Enter the griffin

The griffin (or griffon) is a mythical beast with the body, tail, and back legs of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle. By the Middle Ages, it had assumed legendary status, but the oldest known depiction of a griffin is carved into slate on a cosmetics palette, c. 3300–3100 BC.

Because people in the Middle Ages could read and write, we more or less understand the medieval bestiary, including the legends of the griffin. For ancient Egyptians, Persians, Mesopotamians, Greeks, central Asians, etc., all of whom used the griffin symbol, its meaning is less clear. All cultures, apparently, saw them as supernaturally powerful. And they were thought to be real, if the accounts of ancient naturalists like Pliny the Elder and others are to be believed. The griffin lives on to this day in heraldry, logos and mascots. It meant something to an Egyptian makeup artist, to a feudal warlord, to the Victorian art theorist John Ruskin, and even to animators of Disney movies. Even concrete hasn’t lasted that long.

Art tells the story of human history

The tabernacle and Polygnotus’ paintings may no longer exist, but much ancient art does. We may not know why the unnamed painters at Chauvet Cave painted animals, but there is no question that their art evokes a response in us. For one thing, it’s highly realistic, even when the animals it portrays are extinct.

I wrote on Monday that art history is the pictorial history of mankind. It is the most powerful and enduring record of human civilization, equaling the written word in recording the values, beliefs, emotions, and daily lives of people throughout history. And in general it’s more succinct.

In its narrowest sense, art is visual documentation, and we like to say that purpose has been rendered obsolete by photography. However, if you’ve ever tried to identify a plant, you know that a good botanical illustration is often more useful than a photograph.

More than that, art reflects the cultural, social, and political contexts of its time. It is rich in symbolism, experience, meaning and metaphor. Somehow those elements speak to us even when we can’t put what they say into words.

That is because art works in universal themes, such as love, grief, death, power, or vulnerability.

Art is not a luxury

Art is no more of a luxury than civilization itself, for the two are deeply entwined. That’s why human culture has always supported art, and that’s one of the many stories the griffin tells us.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.