Here are five plein air challenges that will help us all loosen up for the summer painting season. Enjoy!

1. Limited Palette Challenge

Objective: Use a limited palette of only three five colors plus white.

In oils (or other solid media:

In watercolor:

Benefits: This challenge forces us to focus on color mixing, understand color relationships, and create harmony in our paintings. It also helps improve our ability to convey light and atmosphere with a simplified color range.

2. Time Constraint Challenge

Objective: Complete a painting in under an hour. Then do the same subject again in under thirty minutes.

Benefits: Working quickly encourages decisive decisions and helps us capture the essence of the scene without overworking.

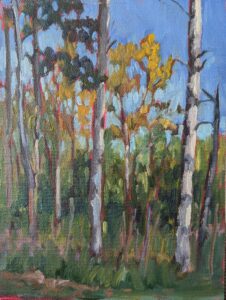

3. Different Times of Day Challenge

Objective: Paint the same scene at different times of the day (morning, midday, evening).

Benefits: This challenge enhances our observation skills and understanding of how light changes throughout the day. It teaches us to depict different lighting conditions, shadows, and atmospheric effects.

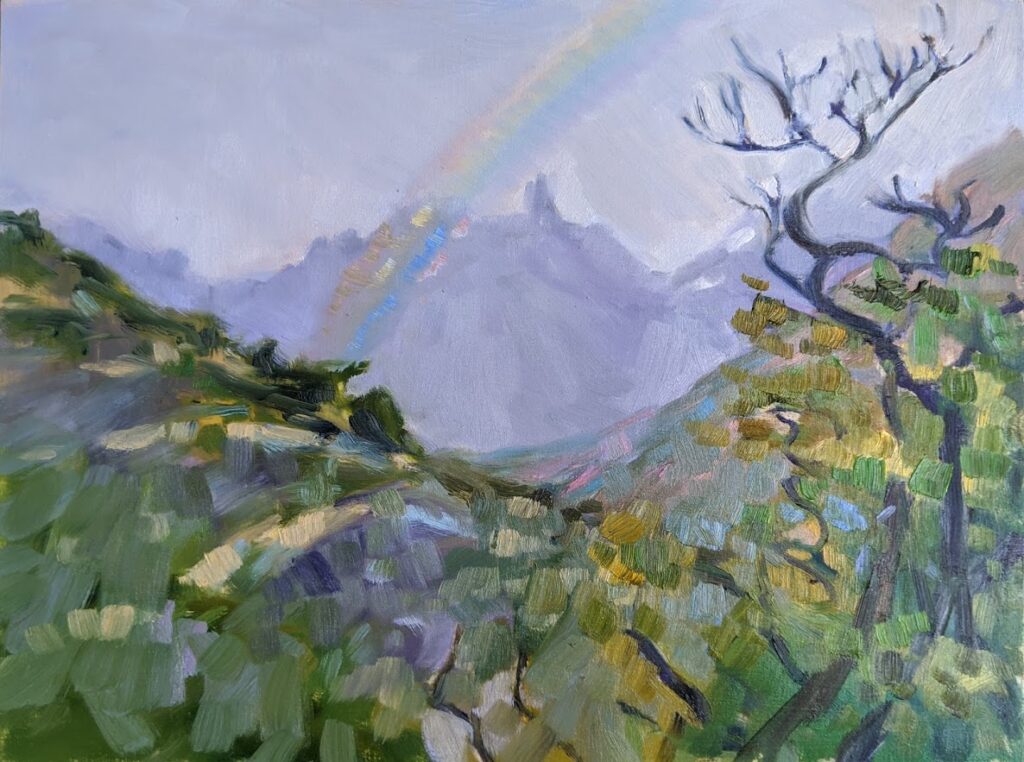

4. Weather Conditions Challenge

Objective: Paint the same scene in sunny, rainy, and/or cloudy conditions. (As they say, if you don’t like the weather, wait fifteen minutes.)

Benefits: Painting under different weather conditions pushes us to adapt to the changing environment and learn to represent different atmospheres and moods.

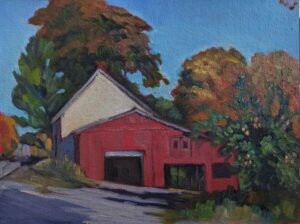

5. Same scene, different subjects

Objective: After choosing your view, paint two different studies focusing on two different subjects within that view. If there’s something in the view that you’d typically shy away from, try making it a focal point. (Except trash; nobody wants to look at trash.)

Benefits: This discourages us from trying to cram everything into a painting. It forces us to spend more time on composition.

Some quick tips for success

If you haven’t already done so, it’s time to set up your kit for summer. One of my resolutions for this year is to repack my kit every time I get home from a session, rather than fussing with it in the morning when I should be painting.

Spend time sitting with your scene before you start painting. The more you look, the better you’ll paint.

Consistency is key. The more you paint, the easier it gets. Don’t get discouraged; think of every painting, good or bad, as a learning opportunity.

Assuming all went well, I got back to Boston last night from my lovely, long, blister-inducing hike. Laura should still be running the office. Just email me as usual if you have questions or problems registering for a class or workshop. (Who am I kidding? She fixes all that stuff anyway.)

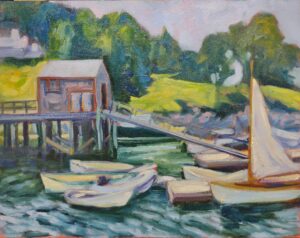

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.