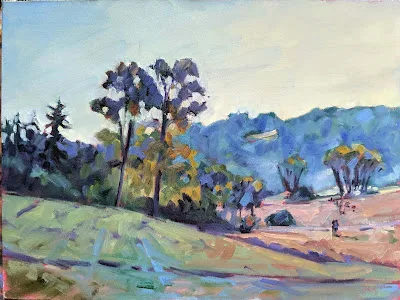

My top five tips to finish a plein air painting in three hours.

Keep your equipment organized

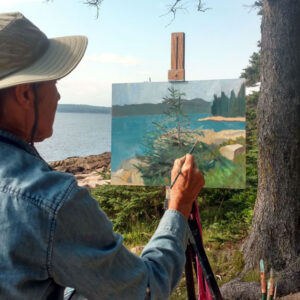

Eric Jacobsen improved my life when he suggested I buy a good, dedicated backpack instead of using cheap gear bags. I bought this Kelty Redwing; you must find the pack that’s sized for you.

When not in use, that pack hangs on the back of my studio easel. With a few exceptions, my plein air kit stays in it. My tubed paints are in a tough pencil pouch (more durable than a ziplock bag), and my small tools are in a zippered makeup bag. The tripod for my easel stays put. The pochade box itself is usually in my freezer in a 35-liter waterproof stuff-sack. My brush cleaning tank is attached to the pack with a carabiner and there’s always a spare canvas ready for painting.

When I get back after a day of painting, I spend a few minutes pulling it back together. Everything goes in its designated place so I can find it when I need it.

I use the same brushes for studio and field work, so they live in a brush case next to my easel when I’m not carrying them outdoors. I clean them when I come in.

When I decide to go out, I can be out the door in a matter of minutes.

Lay out your palette in advance

Cleaning all the paint off your palette between sessions wastes time and money. Only clean the mixing area of your palette, and leave your unused paint for the next session. Or, do as I do and never clean your palette at all. I just knock off any dried paint as it annoys me.

Every palette needs attention at some point (even mine). It’s easiest to reset the colors when you finish for the afternoon, but if that doesn’t work for you, do a reset before you walk out the door the next morning.

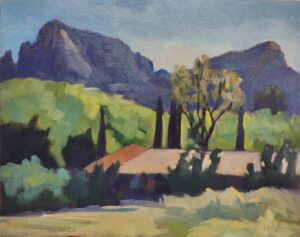

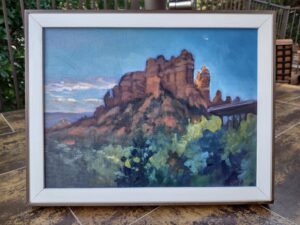

Your palette doesn’t need to be cleaned off before you fly. When I arrive in Sedona on Monday, I can just flip open my pochade box and I’m ready to go.

A sketch in time saves nine

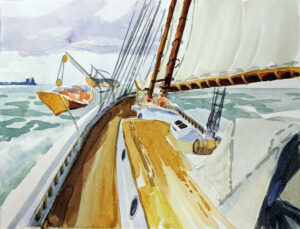

It’s faster and easier to work out your composition with a pencil than to do it with a brush. It’s a lot easier to erase pencil errors than to scrape out bad brushwork-or worse, start again in watercolor. The ten or twenty minutes you spend with a pencil on this first step will save you hours of bad painting later.

Your sketch should lay out your basic composition. The human eye sees value first, so if that doesn’t work in your composition, the painting will fail. “I substitute off-value color and chroma for accurate value. Then, except for a couple spots of high-chroma yellow, I wonder why my paintings are flat,” a student once told me. He took that observation and ran with it, painting only in greyscale for months.

You don’t have to go that crazy, but with every painting, work out the darks to lights in your sketchbook first. Alla prima painting requires great skill in color mixing, because the goal is to nail it on the first strike. You can be off on the hue, but when you don’t have the value right, you start to paint and overpaint passages. That’s flailing, and it kills a painting.

Stick to your value sketch

The worst error of plein air painting is chasing the light. It’s seductive. The shadows lengthen and grow heavier, and you want to capture every second of that transition. You can’t.

If you start with a good value sketch and stick with it, you’ll have a strong painting. That sketch on paper (instead of just on your canvas) gives you reference for when the light inevitably changes.

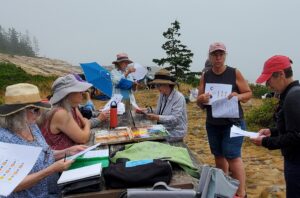

Make sure you aren’t intimidated by your neighbors, who just dive in without sketching and appear to be going much faster than you. The goal isn’t to finish first, but to paint your best.

Don’t fuss with the ending

A good alla prima painting has two or possibly three layers of paint:

- Grisaille or underpainting.

- Midlayer, where the tonal relationships are worked out.

- Finish layer of judiciously-selected detail.

Many exciting paintings are chewed down at the end, when painters perseverate over brushwork and/or details. If you find yourself noodling, stop.

This is not to say that you can’t ever paint in detail. But the ending should be about strengthening composition, not adding last-minute tchotchkes.

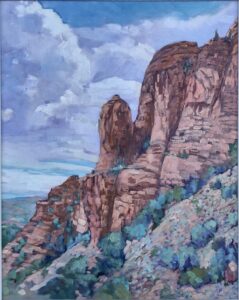

I’m off this weekend to teach back-to-back workshops in Sedona and Austin. There’s still a seat or two left in each (I think), and airfare has dropped considerably since last year.

My first online painting class is up and running, here. It’s called The Perfect Palette and is about the very first step in painting-the paints you should buy.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.