Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays me from the swift completion of my hike up Beech Hill (to paraphrase Herodotus and the US Postal Service). Here in Maine, we dropped into the teens last week. However, the worst hiking was through bucketing rain on Monday. I arrived home soaked to the bone and shivering uncontrollably. My student and friend Amy Sirianni stopped by; I met her at my door in a flannel nightgown and robe because I couldn’t get warm.

What’s a poor New Englander to do when both days and nights turn bitter? My mother used to book a flight to Florida for March or April; it gave her something to look forward to. She didn’t want to come home until winter’s back was broken.

Coincidentally, I’ve ended up doing something similar. At the end of March, I’ll again be teaching in Sedona, AZ and Austin, Texas. Instead of shivering in sleet storms, I’ll be in shirtsleeves under clear blue skies. Alleluia.

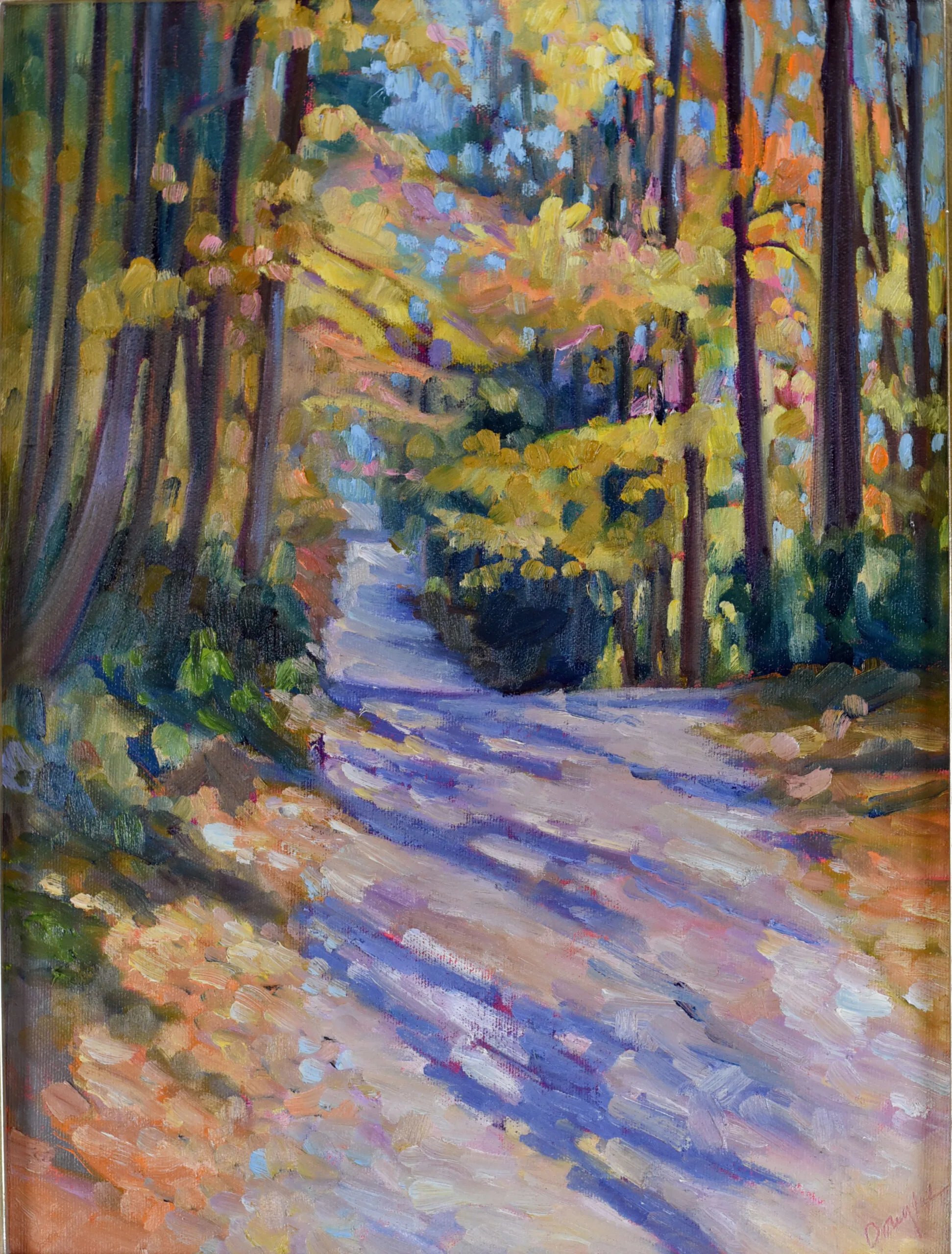

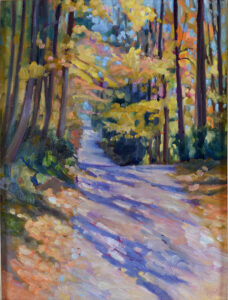

Most of my workshops are on the east coast, which is my home turf. These are the only two workshops I’m teaching in the west (although I dream of reviving Pecos). Western painting is different from New England in atmosphere, color, and vista. I’m grateful for the opportunity to work in both.

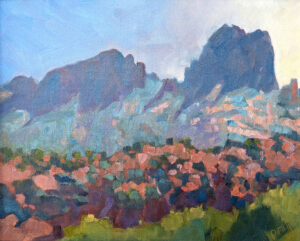

Sedona is a small city of 10,000 people located within the Coconino National Forest. The town is encircled by red sandstone massifs in various stages of erosion. They glow brilliant orange and red in the rising or setting sun.

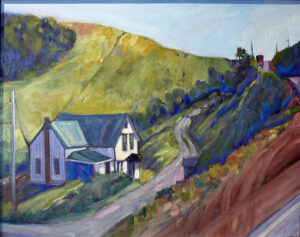

“This color looks exaggerated to me,” I told Julie Richard of Sedona Arts Center when I finished Peace, above.

“It’s not,” she answered, most definitely.

Much of what we paint there are long vistas and those incredible red rocks set against junipers, piñons, and prickly pear cactus. We often paint from isolated trailheads, from which we can sometimes watch vast cumulus clouds form over the buttes and mesas and just as quickly blow away.

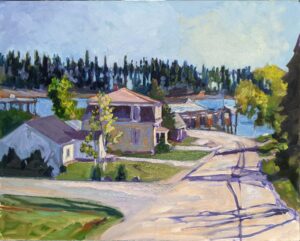

Austin, on the other hand, is the tenth most populous city in the United States (and grown out of all recognition from the first time I saw it). Our painting sites are urban, including the delightful Avenue B. Grocery and Market, where we painted nocturnes and ate fabulous sandwiches last year. Then there’s McKinney Falls State Park with its huge cypresses and turquoise spill basin. That’s where we painted bluebonnets in their thousands. On that magical day, hundreds of birds flew overhead in long, winding skeins.

“Canada geese?” I asked, confused.

“Pelicans,” someone answered.

I find gift-giving challenging, especially for those people on my list who don’t want or need more stuff. I could look at all the catalogs in the world and still not find the right thing for that person who has everything.

For him or her, experiences are a better bet. If you’re looking for a truly unique gift this holiday season that feels extra thoughtful, try a workshop. (And if you want a workshop for Christmas, print this out and leave it someplace subtle, like under your spouse’s coffee-cup. He or she can use the code EARLYBIRD to get $25 off any workshop except Sedona, which is already a discounted price).

Also, if you’re thinking of buying a painting as a Christmas gift (another great idea for the person who no longer needs stuff), let me know soon. I’m my own shipping and handling department and I want to be sure your painting is delivered by Christmas. Until the first of the year, you can use the discount code THANKYOUPAINTING10 to get 10% off any painting on my website.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

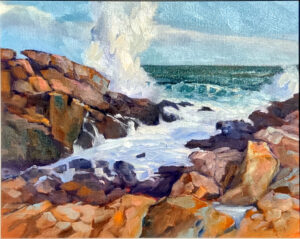

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.

If you missed my North to Southwest virtual opening and have a high tolerance for listening to me drone on, you can watch it here.