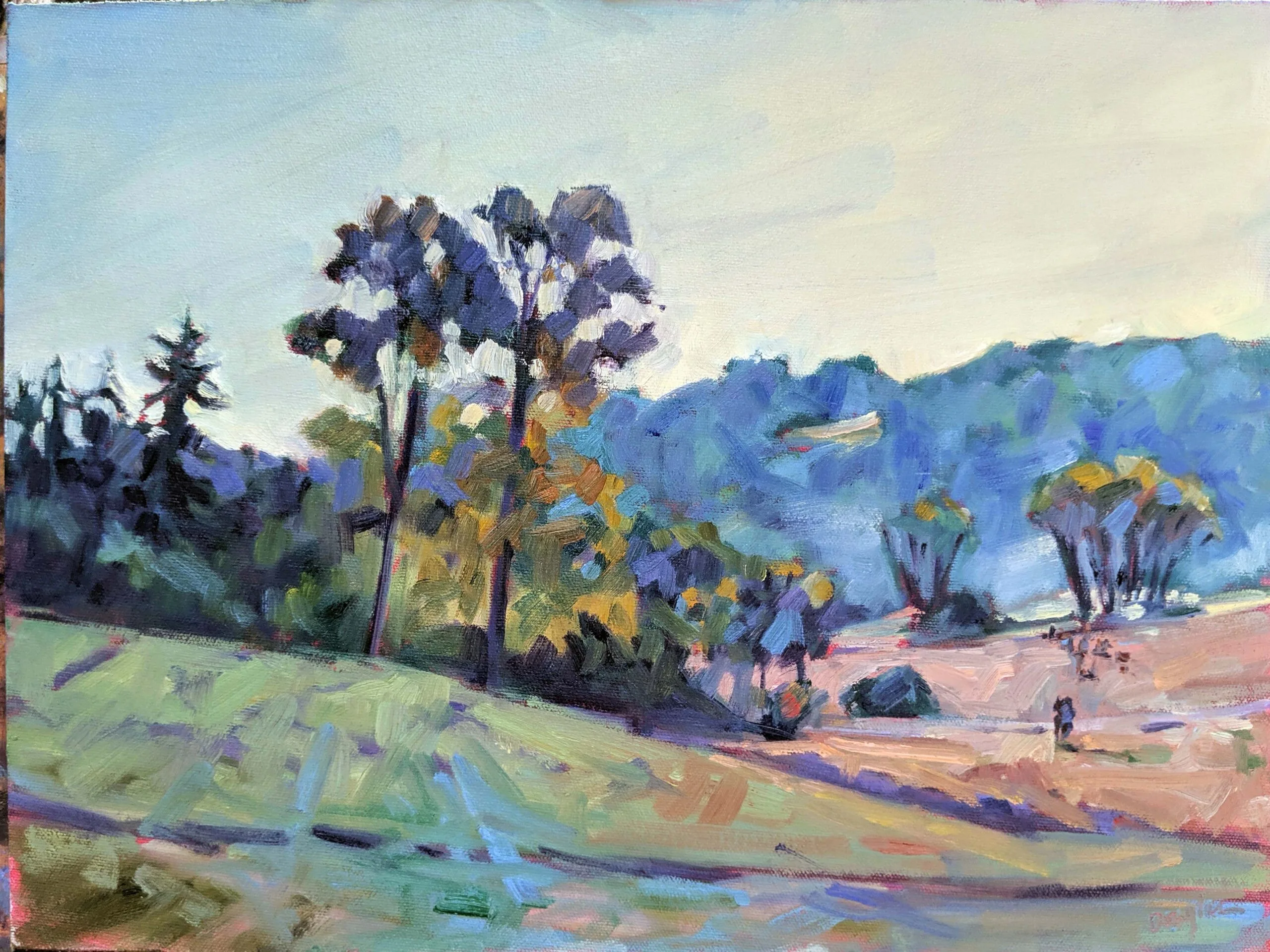

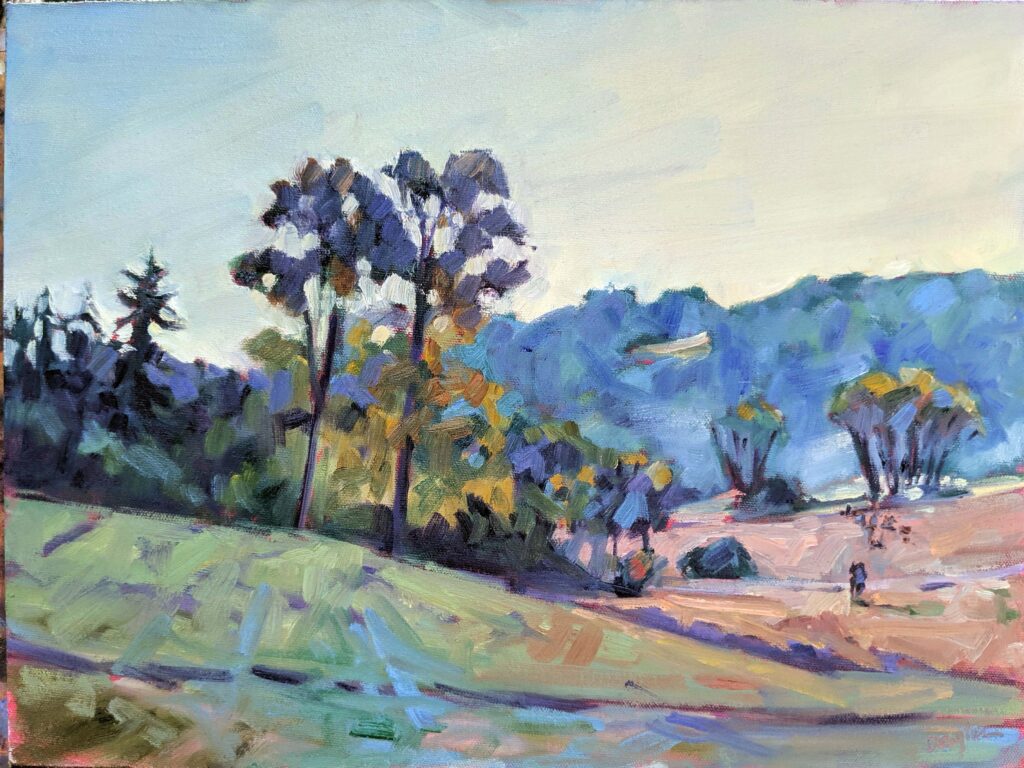

I always mean to go to Perkin’s Cove for its annual plein air event, for no other reason than to see my friends and paint along the Marginal Way. (I could do that any day of the week, but sometimes you need a spur.) This year, I finally fit it into my schedule. Of course, it wasn’t until I was a few minutes out of Ogunquit that I remembered to call one of those friends: my buddy Bruce McMillan. As we were talking, I passed him on the roadside, hauling his kit to the Marginal Way.

Me, living in the past? No way!

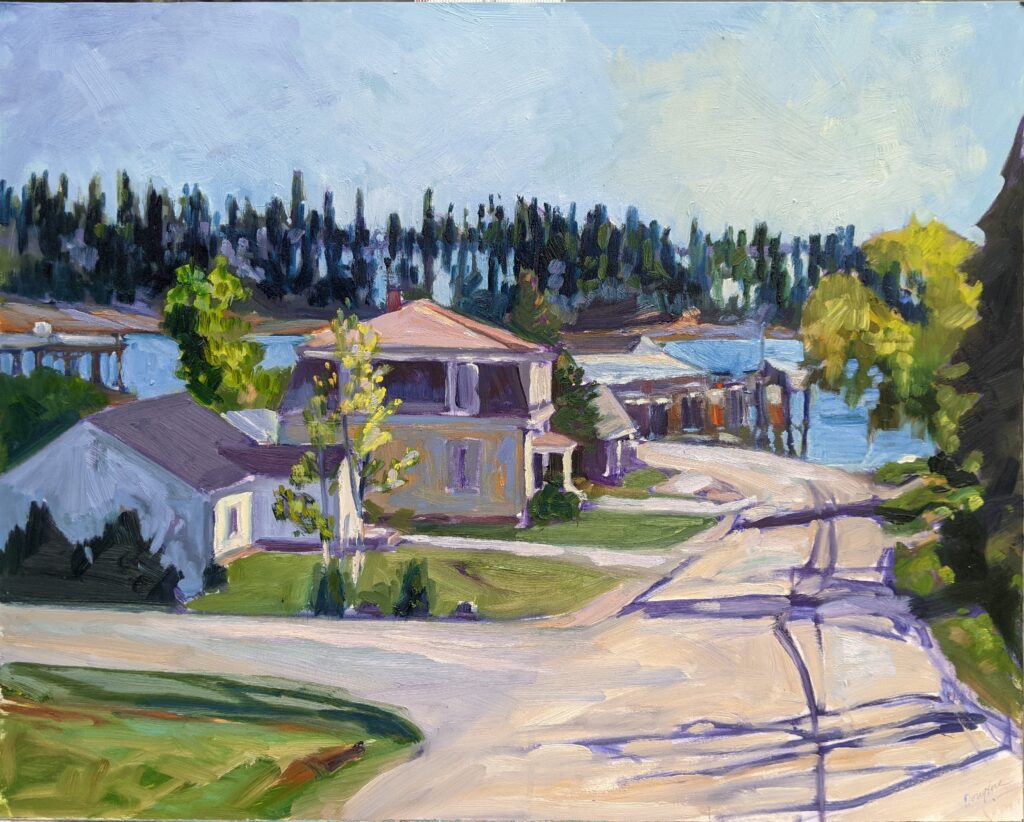

Ogunquit is a place of fond memory for me. I used to take my kids there every other summer when they were small. They’d spend the day paddling in the surf, eat pink hot dogs at Barnacle Billy’s, and then we’d walk along the Marginal Way in the evening. We’d stay with my friend Jan. These days, I drive past her lane and avert my eyes; where there were once small, rustic, seasonal cottages, there are now million-dollar vacation homes.

When my twins were about six, I took them out on boogie boards to a sandbar on the north end of Ogunquit’s ‘puddle’. We had fun playing in the surf, until it was time to go back. The tidal pool that had been ankle deep when we went out was now over my head, and the surf was rolling. I’m a strong swimmer and both girls were good swimmers themselves, but it was all I could do to get them back to shore. I woke up in a cold sweat about it for months afterward. And Ogunquit’s beaches make rip currents and undertows when they feel like it.

Look to the sea

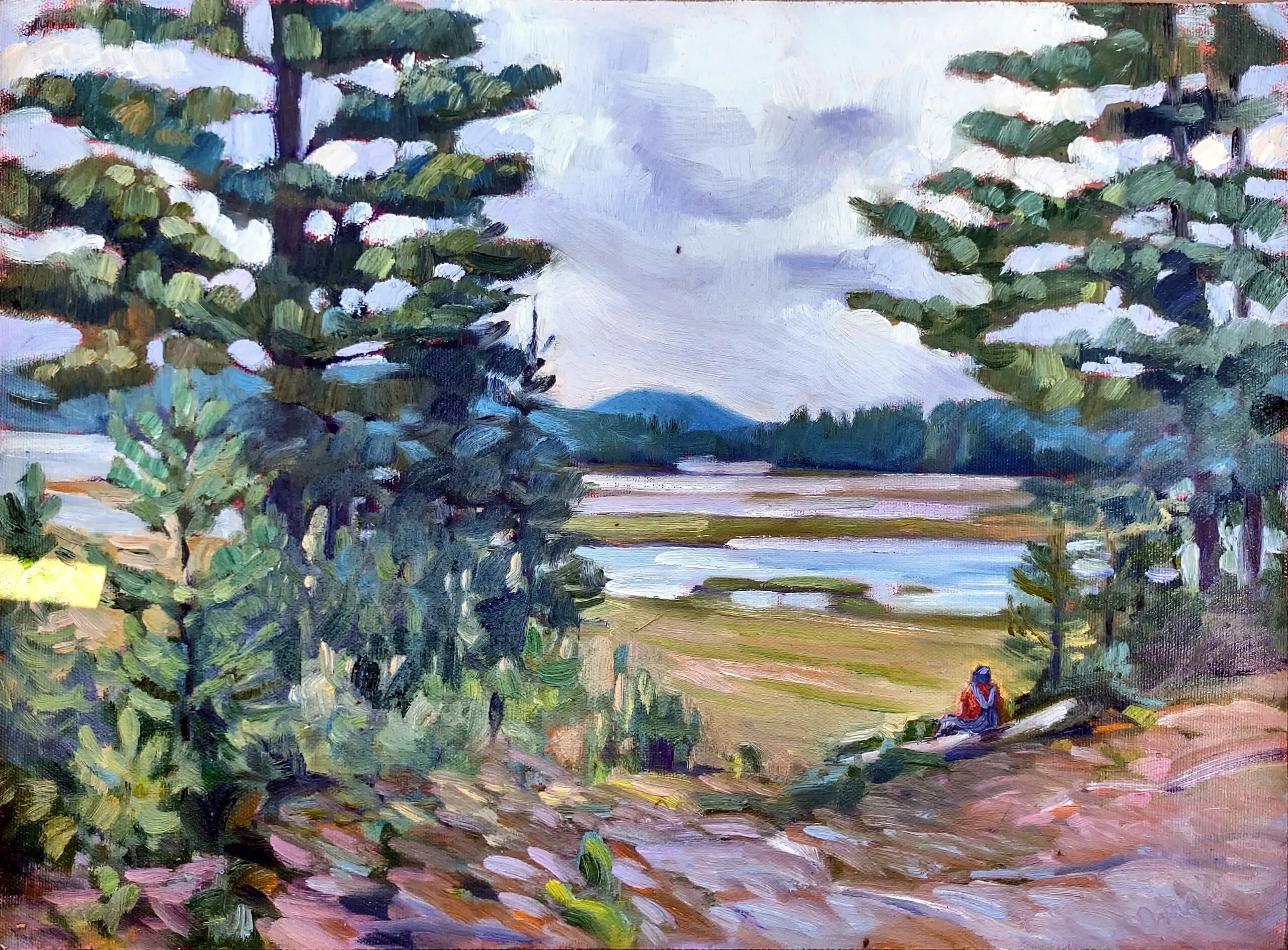

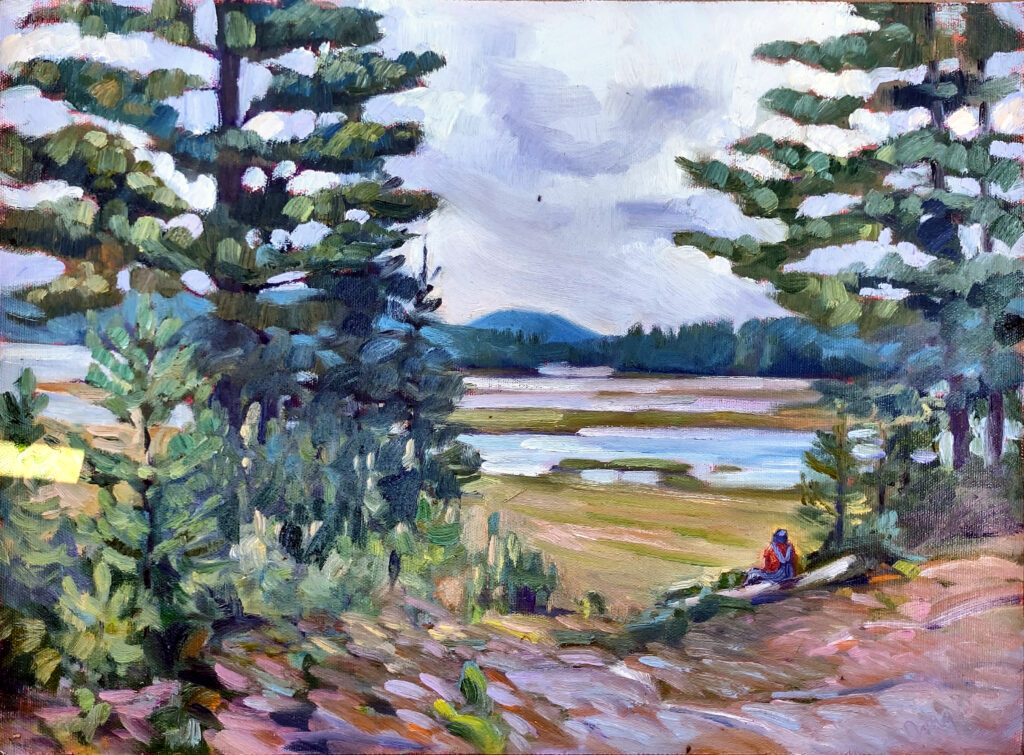

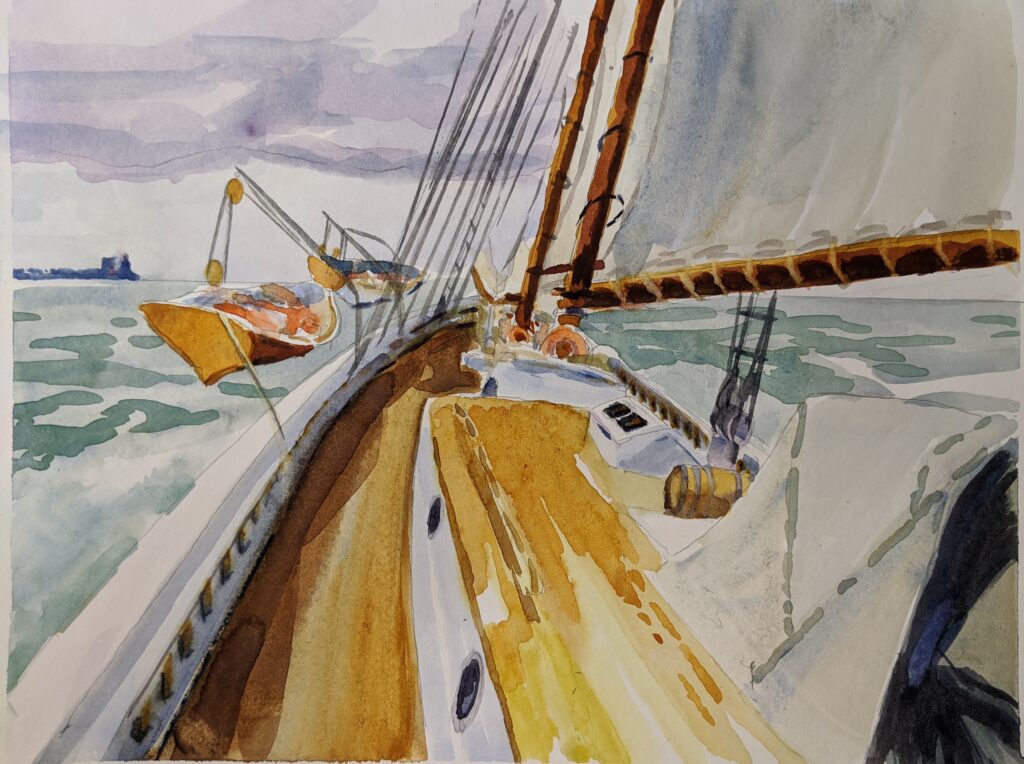

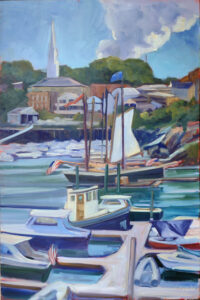

I have been back to the Marginal Way to paint occasionally, and when I face toward the sea nothing has changed. Nor will it, if Nature has its way.

Bruce painted spray in watercolor and I painted it in oils. Every few minutes we would stop and stare openmouthed at the towering surf. It cut down on our productivity, but it was a transcendent experience.

Come see me this evening

I’m not cooking, for which you can all be grateful, but my husband has offered to make his signature bean dip.

Grand opening

Carol L. Douglas Gallery at Richards Hill

Friday, September 13, 5-7 PM

394 Commercial Street, Rockport, ME 04856

For more details, see here.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.