“I realize that my goals as an artist conflict with what I like and what I’ve learned,” a thoughtful reader wrote (in an actual letter, with a first-class stamp). “While I like to call them plein air ‘festivals’, I know they’re competitions designed to provide income to the host of the festival.” They’re promoted to artists as a way to sell paintings, but not all of them deliver equally.

I’ve been corrected when I’ve called these events ‘competitions’, but that’s exactly what they are. If artists aren’t competing directly for prize money, they’re competing for sales.

My correspondent is learning to integrate value sketching and grisaille before going to color. “Taking time to sketch and check values on what I will paint goes against the idea of finishing five or six paintings in five or six days. As it is, I generally finish just three or four paintings in a one-week plein air event!

“Oh, well, I have six to eight months before I apply to one again. That’s plenty of opportunity to speed up my process.”

There’s no doubt that the more you do something, the faster it goes. I am quite capable of doing a value sketch, grisaille and good moderate-size oil painting within a three-hour window, but I’ve been at this a long time.

Another reader visited a large regional festival earlier this year and wrote, “I don’t get why people in the competition bang out crappy paintings in two or three hours instead of spending a day or more doing one good one. You could do four good ones versus six or more crappy ones.

“The current plein air frenzy misses the point of why artists painted outside, historically, and what they really achieved.”

“I think plein air competitions have lowered the quality of plein air painting,” a professional artist told me. He is not talking through his hat; he’s been a prize-winner at top-notch national shows. “That relentless push for quantity floods the market with frankly-mediocre work.”

What’s ironic is that this friend is, himself, a very fast painter, easily capable of hammering out an excellent painting in three hours. But he’s also very tough on himself, and doesn’t submit work that he doesn’t think is up to his own standard. Painting one fast painting is not the same as pounding out half a dozen or more paintings in a week under pressure. That has a way of dulling your compositional and color sensibilities.

No matter how you go about executing your work for a plein air event, quality, not quantity, ought to be the overriding concern.

My personal preference is the event in which each artist can submit only one work. These affairs usually give the artist a few days to execute one painting, and the selling prices are, generally, commensurate. I’m able to relax and think carefully about my approach. Furthermore, 35 painters producing 35 works means sales are more consistent than in a show where forty artists each knock out half a dozen works. Many of the resulting 240 paintings are never sold.

Yesterday I quoted a student complaining about mundane landscape paintings. However, that doesn’t answer the greater question, which is: if it’s not any good, what’s the point in painting it?

I like plein air festivals, and I’m sorry that my current schedule doesn’t allow me to participate in more of them. But I also recognize their potential to be corrosive to the very spirit of plein air painting.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

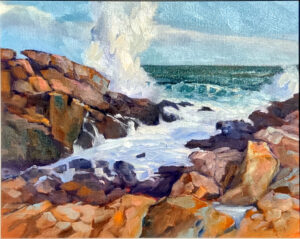

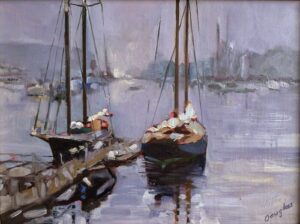

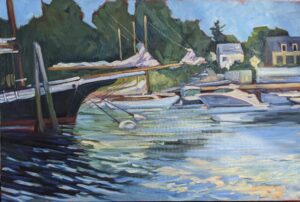

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

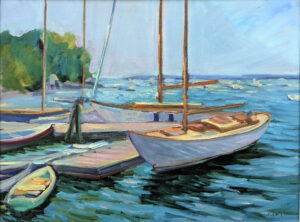

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

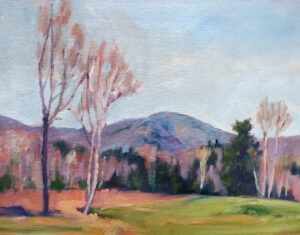

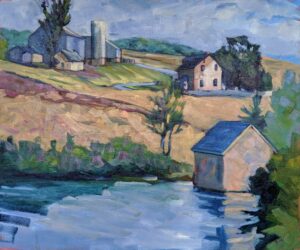

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.