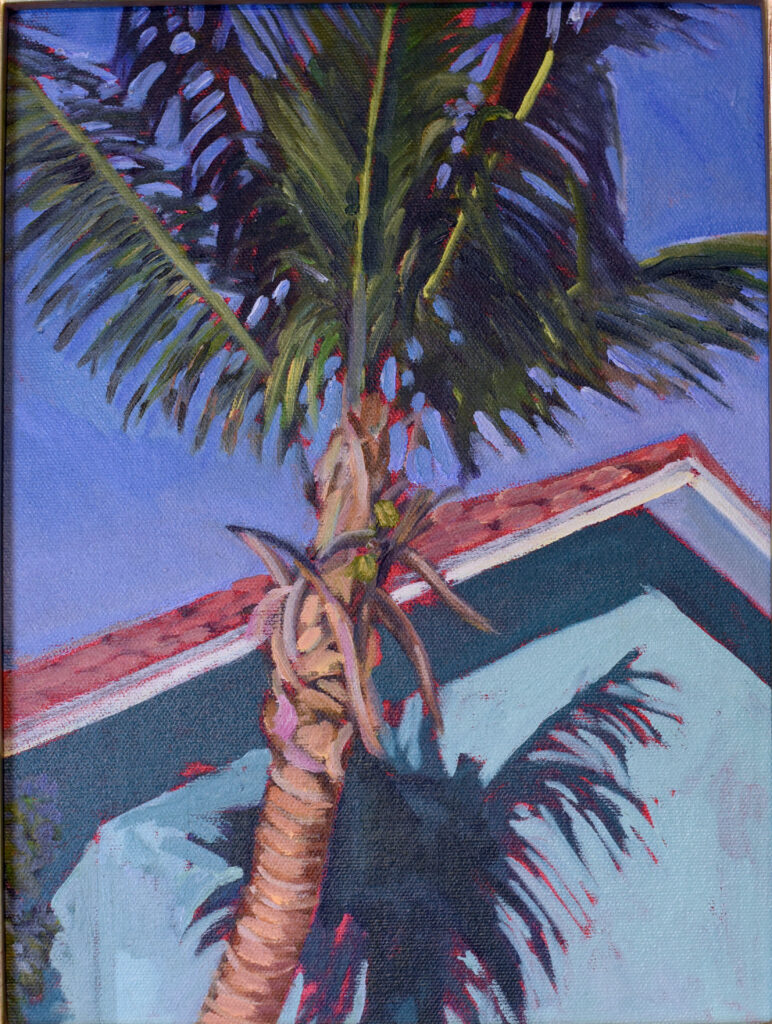

Years ago, Bobbi Heath, Joelle Feldman and I went to the Bahamas to paint. There were many lovely things about that trip, including the warmth. However, I found myself absolutely uninspired for painting. Grand Bahama lacked three variables I crave in landscape painting: variety of foliage color, compelling architecture, and fascinating line. (I’m sure that if we’d been there in hurricane season, the weather would have spiced things up nicely, but alas, it was all calm seas and blue skies.) I have a limited interest in the beach and I came home with very little in the way of finished work.

It was also my first experience in a resort area, and I found it frankly disturbing to be in a place where visitors and natives were so cleanly separated. That’s not something I’d ever seek out again.

An artist born in the tropics might love the subtle variations of turquoise for his landscape painting, whereas I found the gentle surf boring. He, in turn, might find the sulky violence of the Maine surf to be cold and forbidding. He undoubtedly would like conch, and I prefer cod.

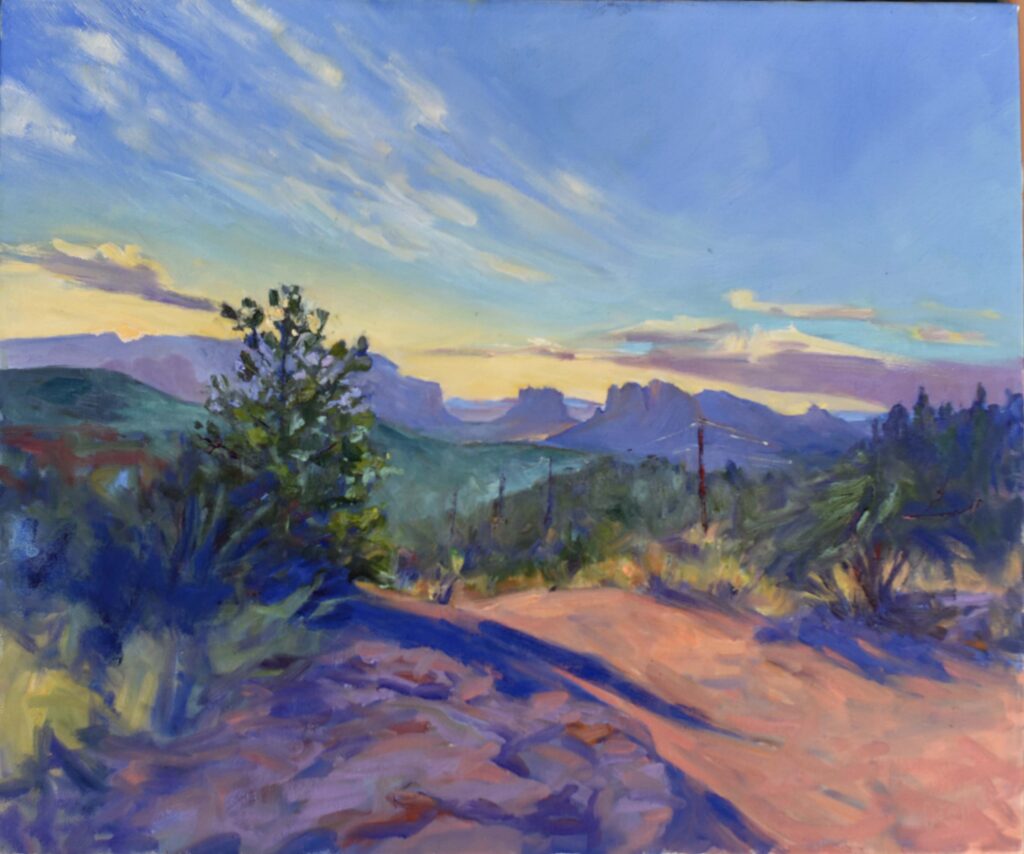

If all goes well, as you read this I’m jetting from Manchester to Malta and Gozo for a week of hiking. I’ve no real idea what Malta looks like, although I’ve dutifully read up on its history. It will, I suppose, be dry, sandy, sunny, and more anciently-settled than most of the places I hike—not too different, I suppose, from the dusty village from whence my Calabrian ancestors emigrated.

Keeping my expectations low—hah!

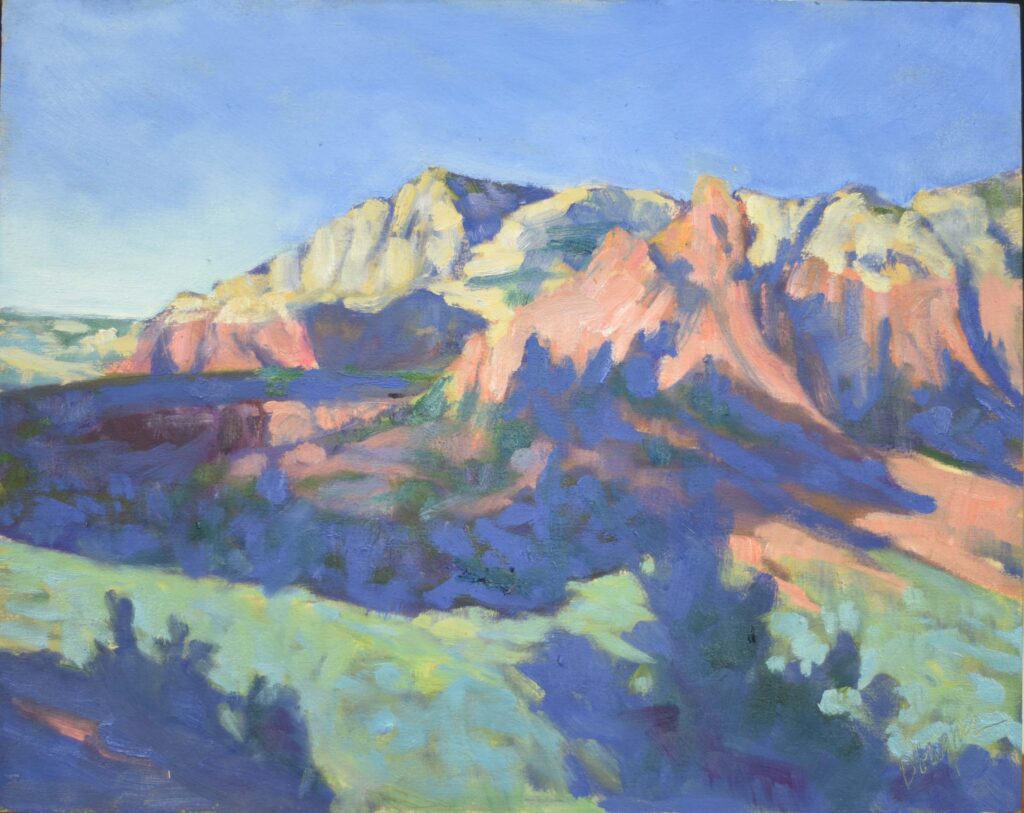

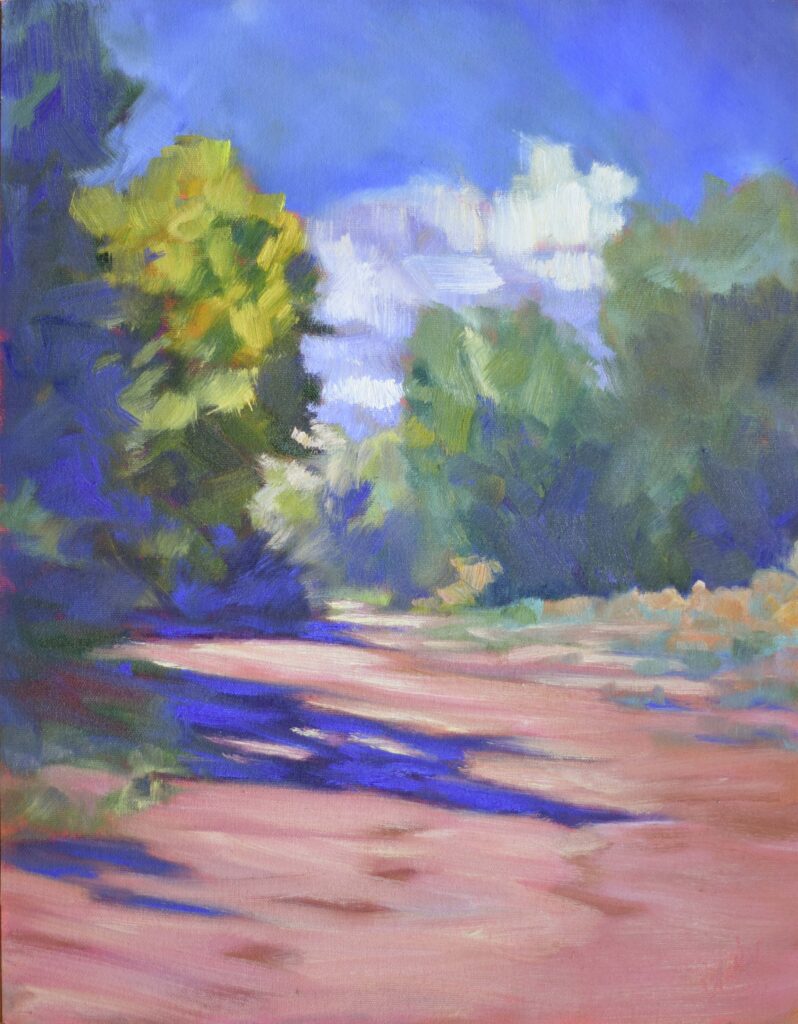

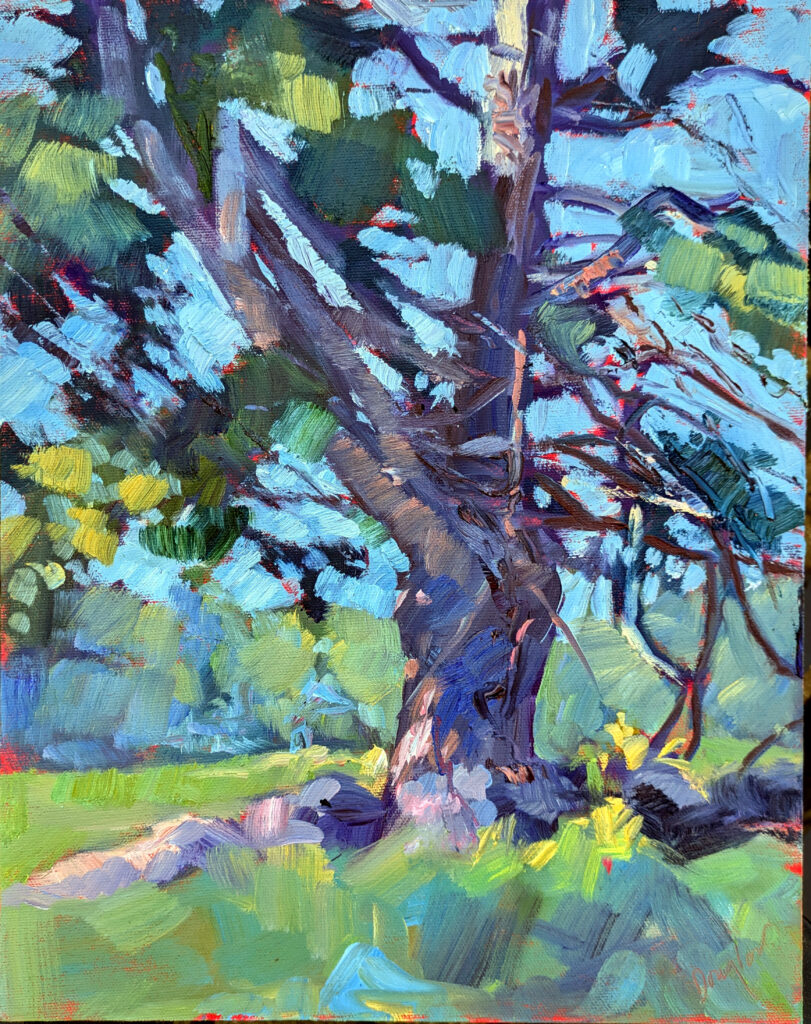

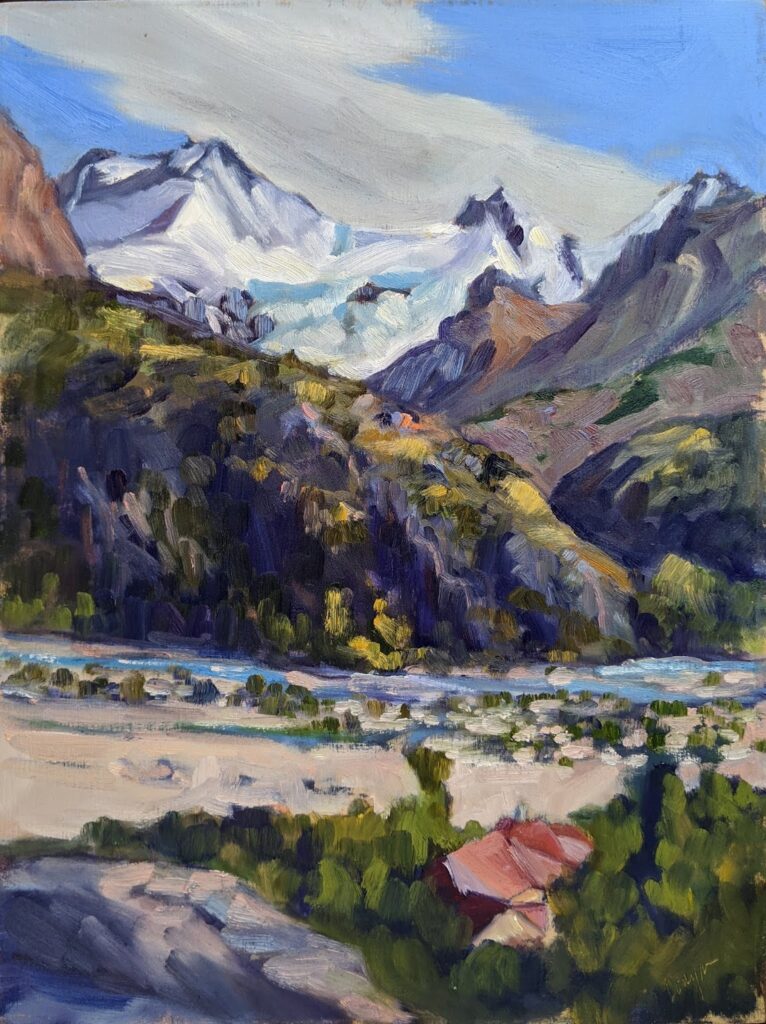

I’ve painted in many corners of the world, and I always tell myself to keep my expectations low, that landscape painting in one place doesn’t necessarily translate automatically to another place.

That never actually works. I’m always carried away.

I’m not taking my oil painting kit, but I will have a sketchbook and a small watercolor kit. In the past on these hikes, I haven’t had time to do much painting. Even when I do, the results are just a passing fury. It’s not just a matter of focus, but of exploration. There’s a difference between landscape painting for finish and effect and plein air painting for exploration and thought. I never seem to move past the latter.

Consider the difference between Thomas Moran’s trail sketches from the Hayden Geological Survey of 1871 and his magnificent oil paintings of the same subject. The sketches are meant to record impressions; the paintings are meant to awe and inspire. Would Moran even have gotten into a major modern plein air event? Perhaps not.

This spring’s painting classes

Zoom Class: Advance your painting skills (whoops, the link was wrong in last week’s posts)

Mondays, 6 PM – 9 PM EST

April 28 to June 9

Advance your skills in oils, watercolor, gouache, acrylics and pastels with guided exercises in design, composition and execution.

This Zoom class not only has tailored instruction, it provides a supportive community where students share work and get positive feedback in an encouraging and collaborative space.

Tuesdays, 6 PM – 9 PM EST

April 29-June 10

This is a combination painting/critique class where students will take deep dives into finding their unique voices as artists, in an encouraging and collaborative space. The goal is to develop a nucleus of work as a springboard for further development.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

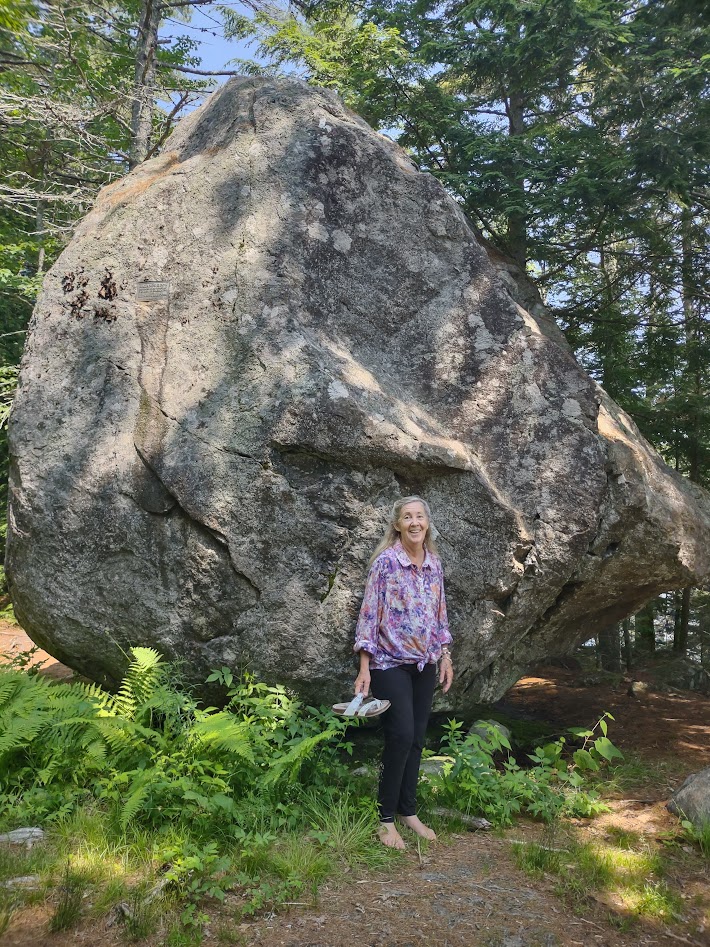

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.