“What will you be teaching in your Zoom class, Advance your painting skills,” asked a prospective student. Unlike most of my classes, I haven’t laid out the curriculum in the online class offering. That’s because it’s, as our British cousins say, going to be a bespoke class. That means it will be tailored to you—your strengths, your weaknesses, your needs, your aspirations.

I’ve been teaching painting online since the world’s annus horribilis, when COVID shut us all up in our little nuclear cells. At first, I thought I’d hate teaching online, but I rapidly became a convert.

The advantages of online learning

In the old days, I’d tour my studio, quietly commenting on work, mentioning what was good and what needed improvement. If Beth overheard what I said to Lynda, that was a bonus, but most people remained in their own little working bubble. Occasionally, if I saw an essential truth that needed mentioning, I’d raise my voice, but that is tiresome for everyone.

That doesn’t happen in Zoom classes. If I tell Lynda, “You should restate the darks,” everyone in the class hears it and consciously or subconsciously checks their pattern of darks.

Students in my classes have come from the United States, Canada and Great Britain—in fact, anywhere there isn’t a language or time barrier. They’ve developed an esprit de corps that would be impossible in the old world of physical classes.

My students have access to recordings of the class, which means that if they must miss one, they can make it up at their leisure. Or, they can review it the class when they need to. That ability to access the content at any time going forward is invaluable. Students can just rewatch the videos until it clicks.

From the teacher’s standpoint, it’s helpful to see students working in their own environment, on their own easels. I have many times caught ergonomic issues in students’ setups that were hampering their ability to paint and draw.

And, of course, people can attend in their pajama pants—and dogs and cats are always welcome.

The internet sometimes gets terrible press… and I get it. There are problems with social media, but the availability of online art classes is a great boon. I started writing this post in Manchester, England, finished it in Reykjavik, Iceland, and you are reading it wherever you are on the globe. Isn’t that cool?

Why am I offering Advance your painting skills?

I’ve had a core group of students with me since I started teaching online in 2020. Many of them are now selling their work, making them professionals. I think it’s a feather in my cap to have helped so many students get to that level, but I need to make room for the next generation of great painters.

That’s why I’ve broken my offerings this spring into two sections. Signature series is intended for those advanced students to develop specific themes in their work. Advance your painting skills is intended to get the next group of painters to that level. You can start as a good emerging artist or a hesitant beginner; there’s a place for you here. Wherever you’re starting, in whatever medium, it’s an opportunity to take a step forward into better technique.

This spring’s painting classes

Zoom Class: Advance your painting skills

Mondays, 6 PM – 9 PM EST

April 28 to June 9

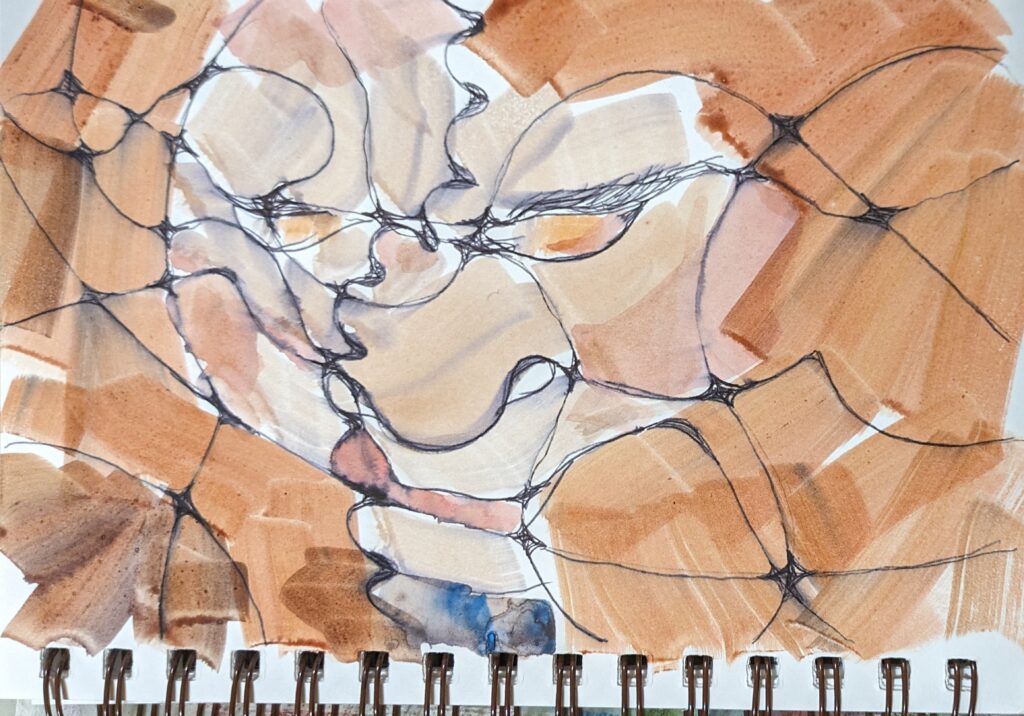

Advance your skills in oils, watercolor, gouache, acrylics and pastels with guided exercises in design, composition and execution.

This Zoom class not only has tailored instruction, it provides a supportive community where students share work and get positive feedback in an encouraging and collaborative space.

Tuesdays, 6 PM – 9 PM EST

April 29-June 10

This is a combination painting/critique class where students will take deep dives into finding their unique voices as artists, in an encouraging and collaborative space. The goal is to develop a nucleus of work as a springboard for further development.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.