Watercolor brushes are softer than oil-painting brushes. The most expensive are sable brushes. Natural bristles combine strength with suppleness and hold more paint than synthetics. However, there are some fine synthetic brushes out there. Several of my go-to brushes are Princeton Neptunes.

Unlike oil-painting brushes, watercolor brushes should last a lifetime, so buy the best you can afford. The only absolute rule is to never leave them standing in water. Set them down flat between brushstrokes and rinse them thoroughly when you’re done. Unless you’ve done something ghastly, they need no soap or detergent and very little agitation to clean.

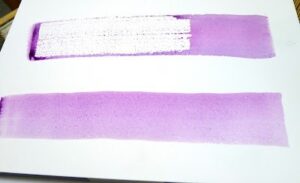

In general, watercolor brushes drop more pigment the more vertically they’re held. You can use this to move from a filled area to a broken one in one brush stroke. In all the following examples except for the mop, I’ve held the brush both ways. A good rule is to carry the vertical brush slowly and in a controlled manner; pull a horizontal brush more rapidly to get the least amount of paint contact with the paper.

The brush I used for the photo montage above is a 2″ flat synthetic mottler or spalter brush. I like this shape for both oils and watercolor. It’s a relatively inexpensive brush that gives a beautiful wash. It’s useful for covering large areas quickly, but with precise edges.

Flats and brights give you nice flat washes, but can be used to make expressive lines as well. Brights have more control and carry less paint, just as they do in oil painting. Turn them on their sides to make a controlled line. Twisting the brush while painting gives an infinite variety of shapes. So too does varying the ratio of paint and water.

Because of the way watercolor bleeds, its brushes can be used in ways not possible in any other medium–a long blend of different pigments, or by painting a shape in clear water and then dropping pigment into it.

I don’t normally carry riggers with me in either watercolor or oils. (They’re meant to paint perfect lines, and my world-view doesn’t include many perfect lines.) Most of my line work is done with rounds. They do not give as much control on long lines, but they are very expressive.

Squirrel mops are the most uniform wash brush you can use. It’s virtually impossible to make them skip, so use them where a lovely flat wash is a goal.

But a good mop can also point, hold vast amounts of paint and sweep across the paper in style.

Natural sea sponges are multi-purpose painting brushes. Use them to apply or remove paint. They can be as subtle or bold as you wish.

Of course, for plein air painting, a little goes a long way. If I could carry only one watercolor travel brush, it would be the Escoda Reserva Kolinsky-Tajmyr Pocket Brush. It’s compact, comes in a protective tube, and makes an outstanding range of marks. A close second, at a lower price point, are the Da Vinci Cosmotop Spin Travel Brushes. A hat tip to Heather Evans Davis for introducing me to them.

Your brushwork contributes immeasurably to the quality of your painting. Don’t dab or be diffident; plan your strategy and then execute it with boldness. To do this, of course, you must practice. Take lots of practice shots on scrap paper; they’ll never go to waste.

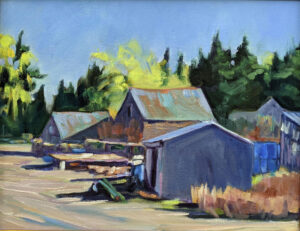

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.