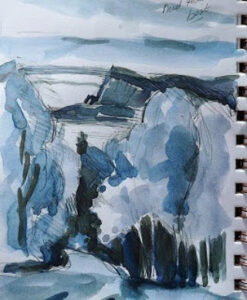

I just got off schooner American Eagle, where I was teaching watercolor. (Next year’s workshop will be September 15-19, but the details aren’t solid.) I always have a few beginning painters mixed in this group. They start not believing they can do it, and end by feeling they’re on the road to mastery. Painting is hard, but anyone can learn it.

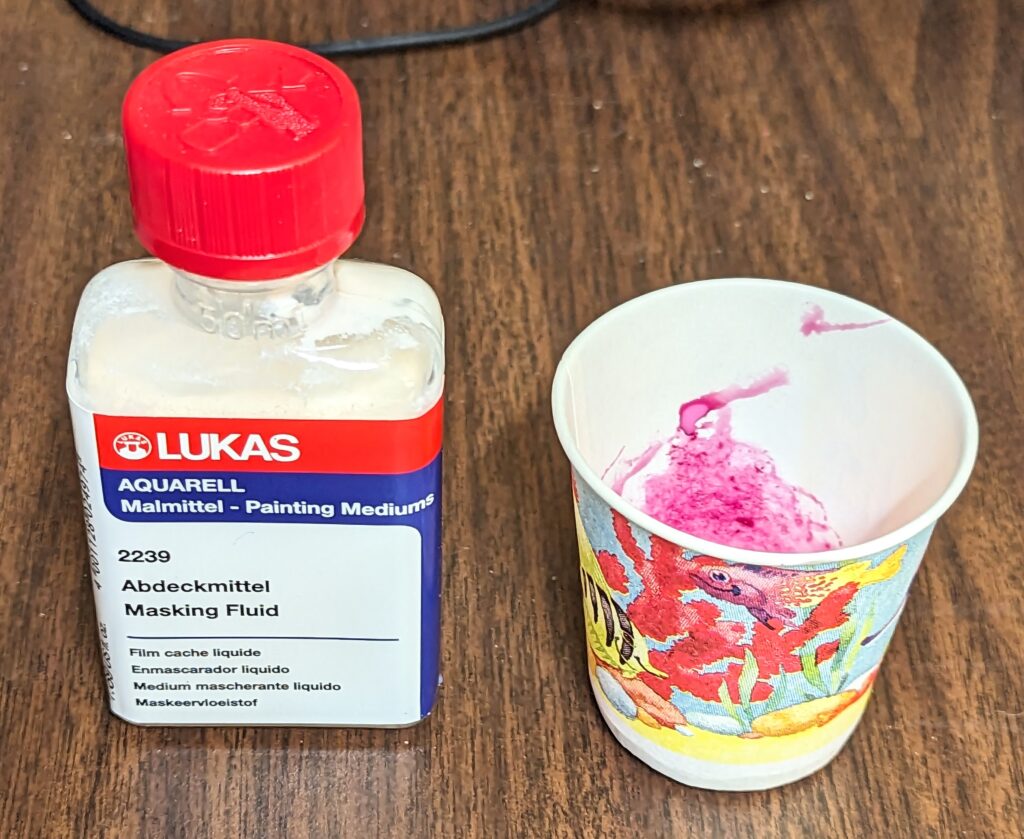

Materials

This is an area where beginning painters can go spectacularly wrong, buying hundreds of dollars’ worth of stuff they don’t need and won’t use.

Often, beginning painters will buy cheap materials because they’re worried they might not like painting. That’s akin to buying a kazoo and deciding that you can’t make music. Bad art supplies will just frustrate you.

The inverse of that is buying lots of stuff you don’t need, because you’re not sure what is necessary. I freely distribute my supply lists for watercolors, oils, pastels and acrylics. If you stick with them, you can paint for the lowest cost possible.

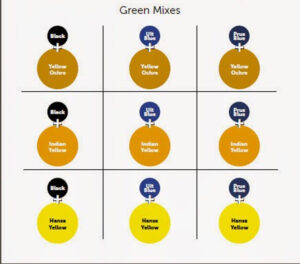

My online class, The Perfect Palette, is meant for oil painters, but beginning painters in any media will benefit from learning how pigments work.

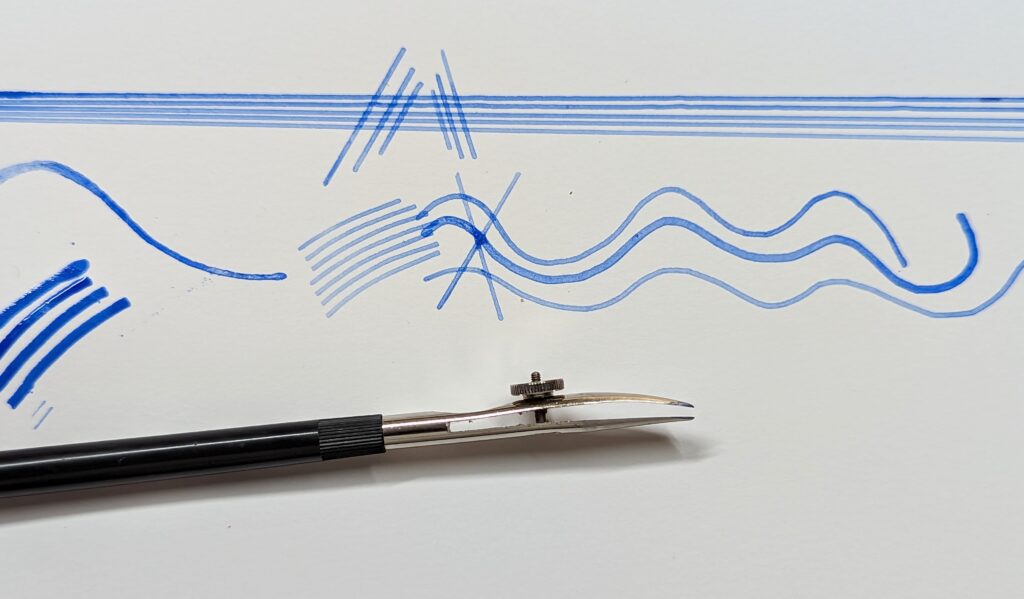

Drawing

Drawing is the human’s basic tool of communication, and it’s never more important than when planning a painting. The good news is, anyone can learn to draw. If there’s not a class near you, start with this book.

Classes and workshops

Classes and workshops are enormously helpful, which is why I teach so many of them. But a class is only as good as its teacher, so ask around. If you’re not interested in a classical style, an atelier might not be the right place for you to study. Likewise, a loosey-goosey class will drive a serious student mad. There are plenty of good, conscientious teachers out there who steer a middle course. Wherever you go, make sure the teacher follows an accepted protocol of painting and knows how to teach it.

Don’t rule out an online class. I’ve been teaching online since the pandemic, and I believe students learn more from it than from live weekly classes, because the interaction is, paradoxically, closer.

Inspiration

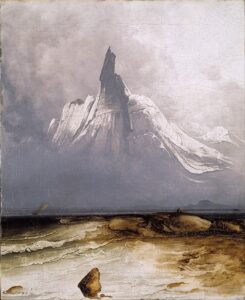

Most new painters start working from photographs. However, painting from life is much more instructive. Photos distort size relationships and colors, and they do all the thinking for you. Even experienced artists can find themselves slavishly following the photo instead of using it as a starting point.

You can paint any subject for practice: the house across the street, your tree, or an old barn you love. Seek out a plein air painting group in your area to give you the courage and camaraderie to paint in public. If the weather is bad, set up a still life in a corner of your studio and paint that. Anything can be a still life, including your sleeping dog, the jacket you threw over a chair, or your kids’ toys.

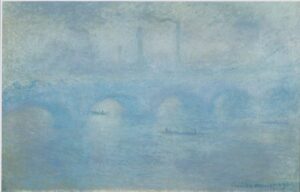

Developing your own unique style

In short, don’t worry about style. It comes from assured brushwork and color management, and those come from practice. Seeking a style in the early days of painting just puts you in a box that’s hard to escape. Instead, let it develop naturally, over time.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

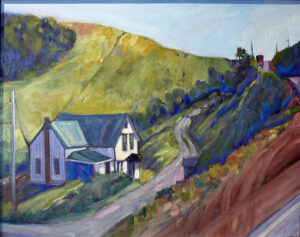

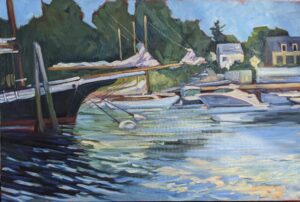

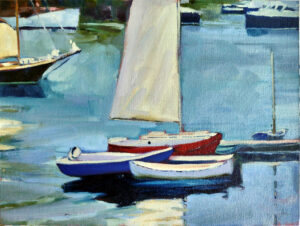

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

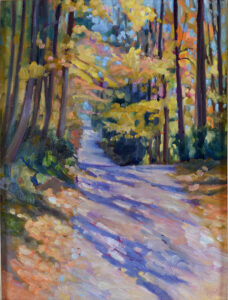

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.