Witness this exchange:

“You should do more plein air events,” said A. “You’re a good painter.”

“I don’t enjoy them,” said B, who’s older and wiser. “I find them almost painful.”

“But they’re good for you,” insisted A.

I don’t think A’s comment was malicious. She works the plein air circuit. She can’t conceive of an art career that doesn’t involve competition. On the other hand, B has an extensive resume that includes signature membership in several prestigious national organizations. For her, plein air events are too much effort for too little return.

I love plein air events myself, but they have their downsides. There are often more artists than the market can bear, resulting in bargain-basement pricing. They can encourage artists to churn out quantity instead of quality. Without a good gallerist to guide buyers, sometimes sentimental dreck goes for good prices and fine paintings are ignored.

They can be nerve-wracking. I once did an event with a very fine painter who downed four glasses of wine in rapid succession before he could go to the awards ceremony. He took first place, but that is not a healthy way to run your art career.

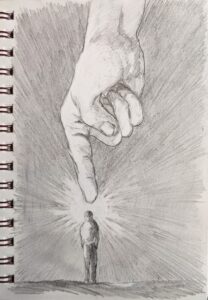

Underlying A’s comment was the assumption that growth comes only through pain. Sometimes that’s true, as anyone who’s been through the creative desert can tell you. (The desert is a necessary step in growth, but you don’t realize that the first half a dozen times it happens to you.)

It’s equally true that growth comes through joy, quiet reflection, prayer, thought, or going for a walk. Each time I held one of my children for the first time was a transformative moment. It was joyful, but it came with the realization that my life was changed forever. A wedding is like that; so is getting your first dog. All have the potential to make you a better person, and the mechanism for that is joy and a determination to live up to the promise of the moment.

I had two influential painting teachers. First was my father, who was often irascible but who taught me to draw and paint with great patience. Then there was Cornelia Foss, who is as tough a nut as ever came out of the Upper East Side. I’m not easily cowed, and I learned a great deal from her. However, my friend and sometimes-roommate Peter was a much gentler soul. I don’t think he ever finished a painting in her class. He would pluck his eyebrows out in frustration and anxiety. He’d make a good start and then wipe it out, he was so nervous. Cornelia’s indisputable genius landed on stony ground because he was so daunted by her. That’s pain to absolutely no purpose.

The second problem with A’s comment is that there is more than one way to skin a cat. (Sorry, Wylie.) My own path has been very different than A’s or B’s, but it has worked for me. Chutzpah seems to be a specialty of our age, and we’re all quick to give unsolicited advice, myself included. But if someone doesn’t seek our opinion, we don’t need to give it. If someone doesn’t depend on us for support, we can let them make their own choices. There are many routes to the same goal and what works for one person may not work for the next. That’s a big part of what makes life so beautiful and fascinating.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

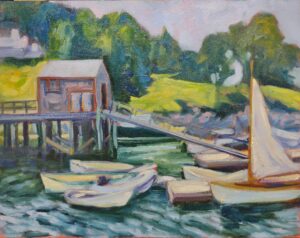

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

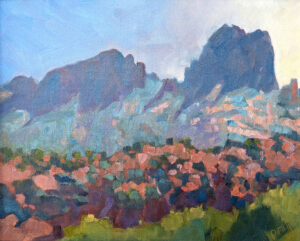

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

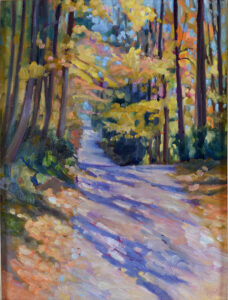

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.