“I’ve done a lot of drawing in pencil and charcoal, and anime and computer art, but I don’t know how to paint,” a young man told me. He wanted to know how to learn painting starting from the very beginning.

I checked his drawing portfolio (because if you can’t draw, you can’t paint) and he has good chops, including work from real life. He is ready to start working in color. But since he can’t break free to take one of my workshops this summer, what can he do?

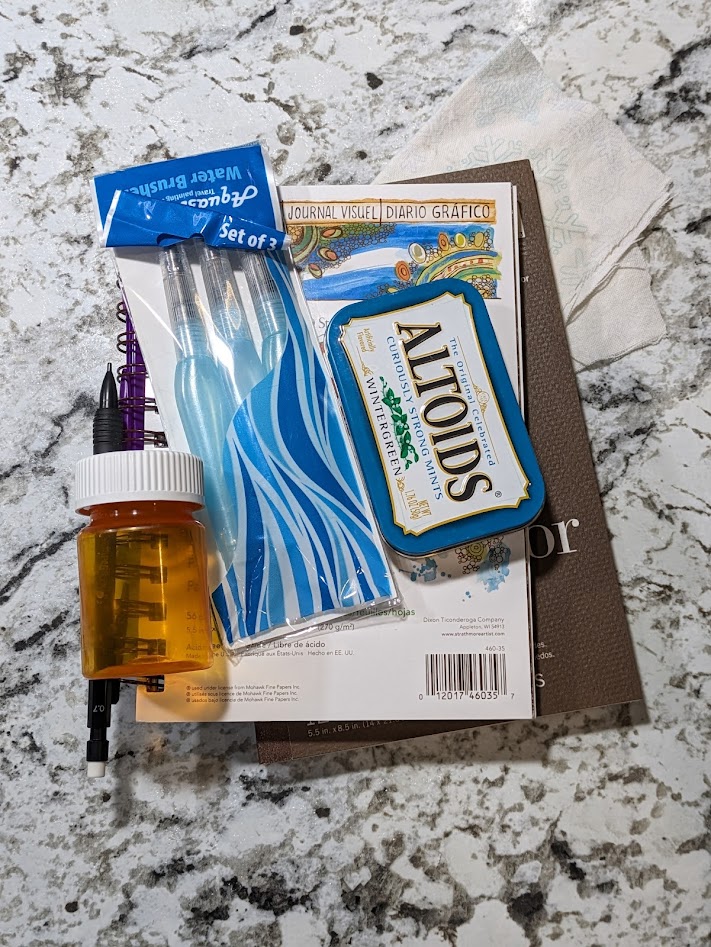

First, I signed him up for Seven Protocols for Successful Oil Painters, my self-directed how-to-paint class. I’d rather people took the first section before they ever bought a single tube of paint, because Step 1: the Perfect Palette, explains in detail why I recommend paired primaries to my students. Then I gave him a mini-kit of QoR watercolors in quinacridone magenta, nickel azo yellow and ultramarine blue, a Pentel water brush, two bound Strathmore watercolor pads, a soft flannel rag and a small bottle to hold water. Even though he’s interested in oils, that is a cost-effective first introduction to color. (And, no, I can’t afford to send you all starter kits; he just caught me on a good day.)

But here’s a step-by-step guide on how to learn painting for the absolute beginner:

Gather Supplies

If you’re unsure whether you want to pursue painting, go with the kit I outlined above. If you know you want to paint, here are my supply lists for oils, watercolors, pastels and acrylics. These are based not only on my own usage, but on decades of students’ comments.

Learn the basics

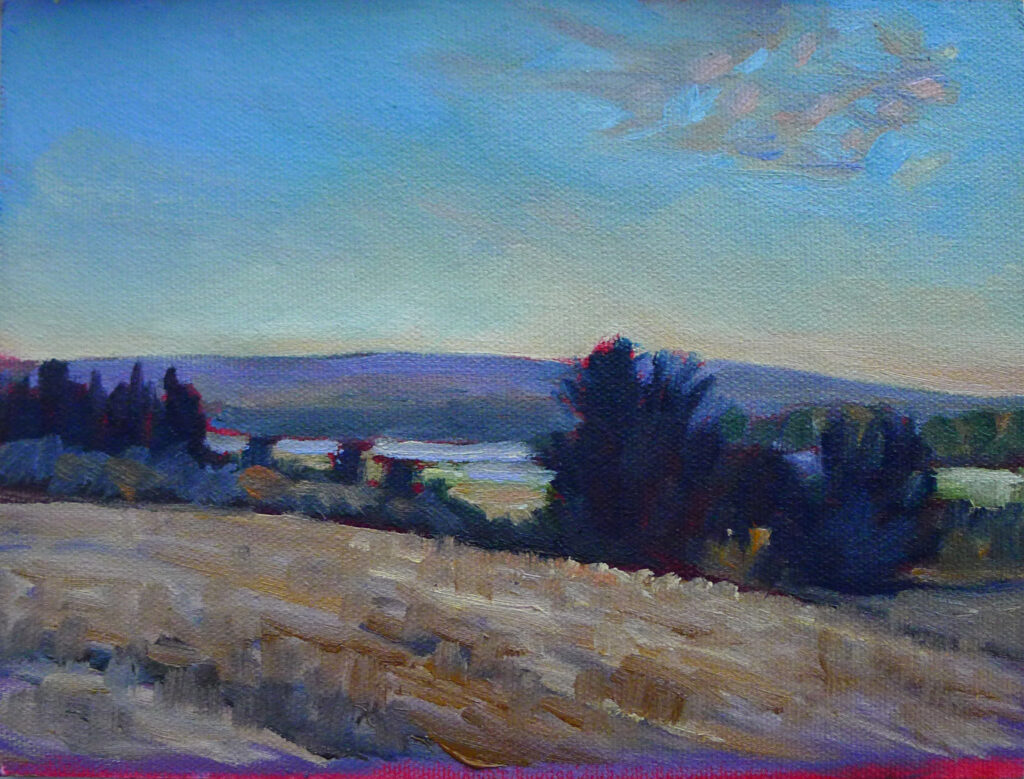

You’ll need to understand color theory, how to mix colors, basic brush techniques and fundamental rules of composition. In addition, you need to understand the basic steps from drawing to value study to final painting. You can get that from my classes and workshops, or from the self-directed Seven Protocols, above. If you prefer to read, I recommend Kevin MacPherson’s Landscape Painting Inside and Out for oils and Gordon MacKenzie’s The Complete Watercolorist’s Essential Notebook for Watercolors. However, there are many good books out there. (And I’d love your recommendations in the comments if you have favorites. I’m not that ‘booky.’)

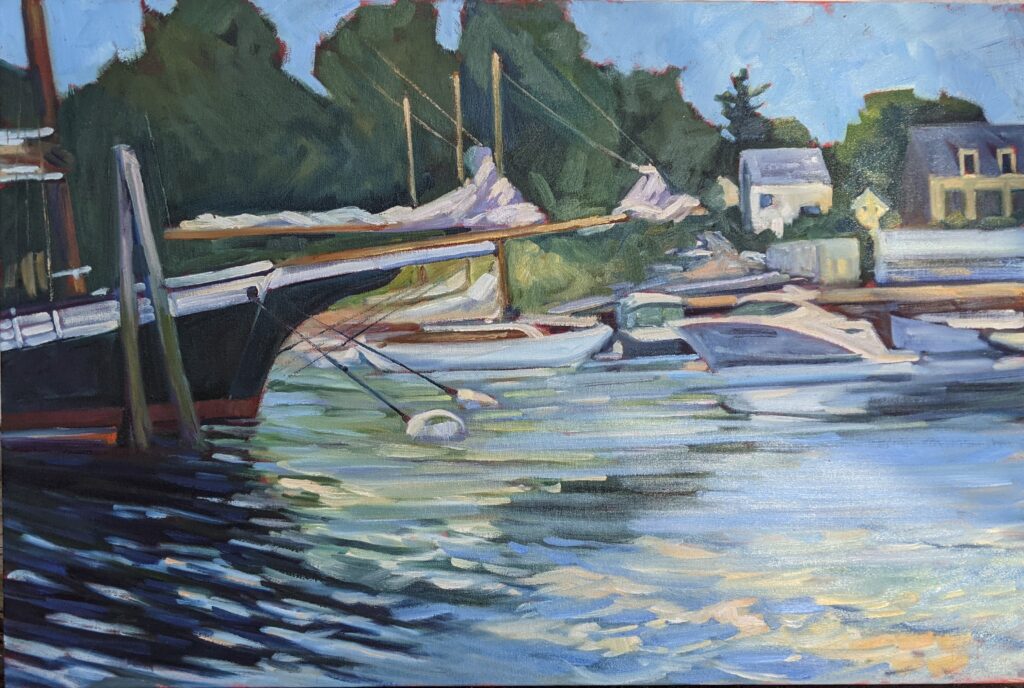

Find a group of fellow enthusiasts and practice regularly.

“Iron sharpens iron,” and you’ll learn from your fellows at least as much as you do from your teacher. Investigate plein air groups, figure painting groups and urban sketchers for opportunities to paint from life. Plein air painting with a group isn’t just about becoming a better painter; it changes how you see your home turf. I’ve learned about many great parks, museums and gardens from my fellow painters.

Study art

Read about art history and visit galleries and museums. There are many ways to put down paint, and art history gives you a capsule lesson in all of them. You will also start to understand why modern artists paint the way we do, and where you fit in on the great continuum of art.

Seek intelligent feedback

I’m a little nervous about social media groups or local art clubs for critiques, because some feedback is worse than none. Sometimes people repeat untrue cliches about painting. Others have axes to grind.

However, there are some very smart people out there, and they’re worth cultivating. My best feedback comes from my students (who aren’t afraid to tell me when I go off the rails) and my family. And I apply the same rules of formal criticism to my own work that I teach.

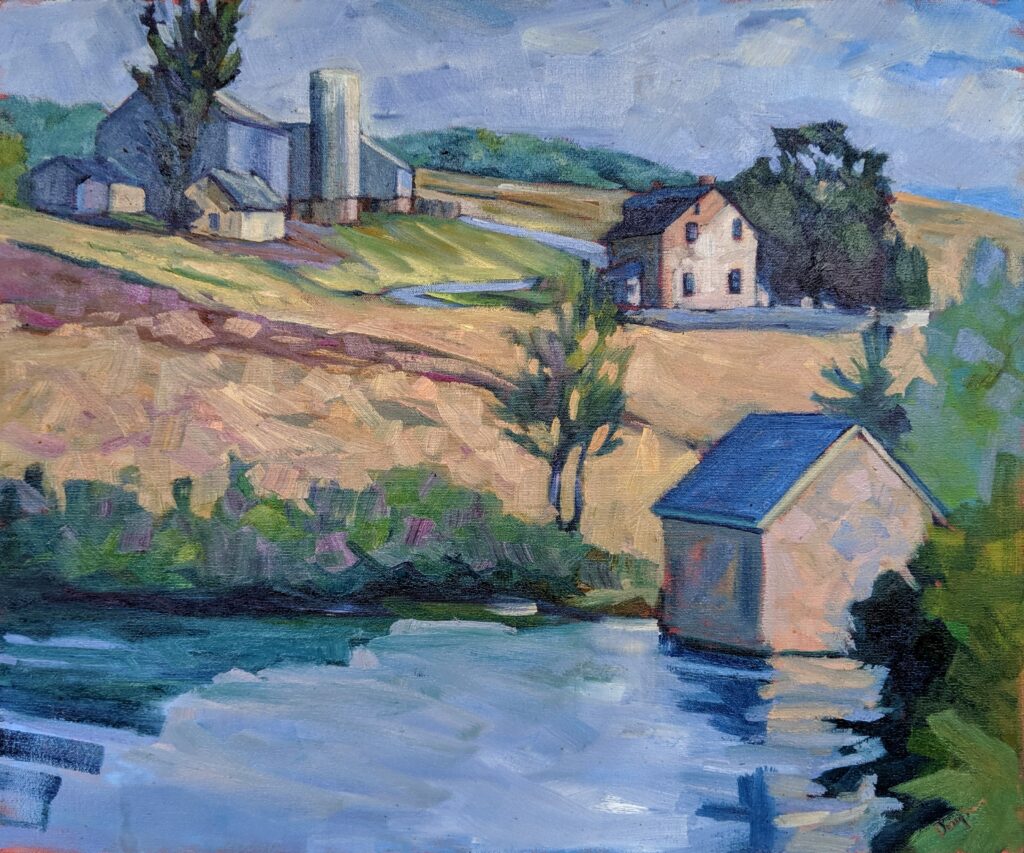

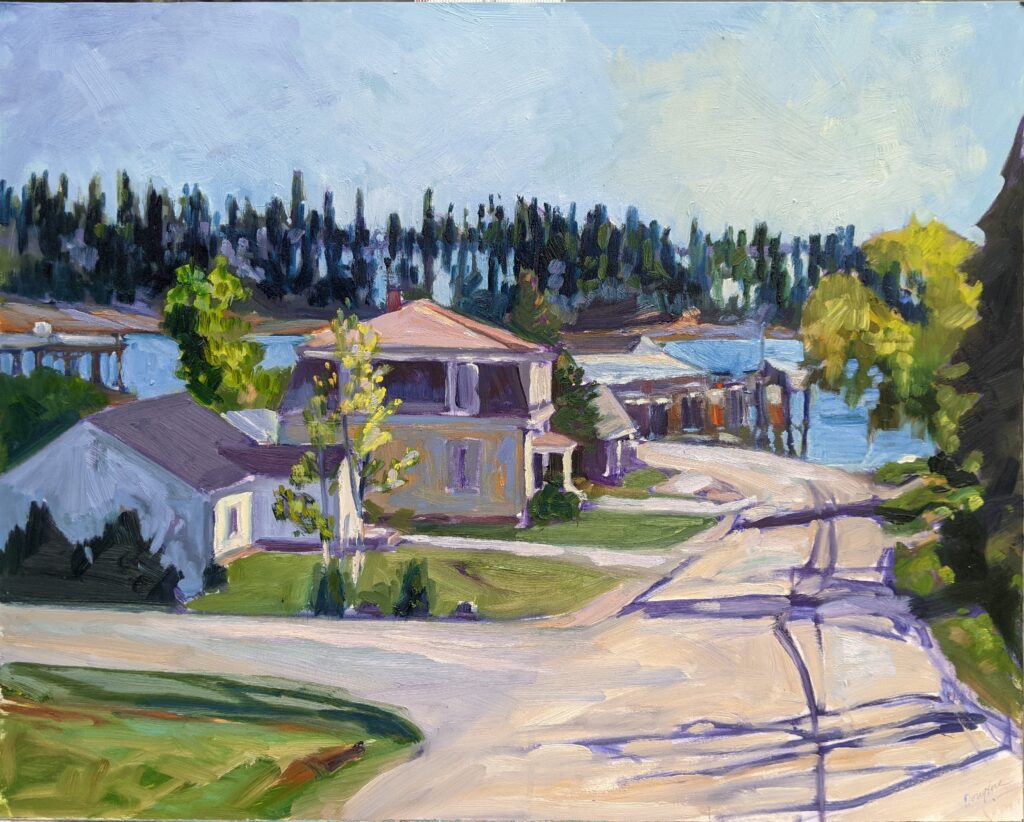

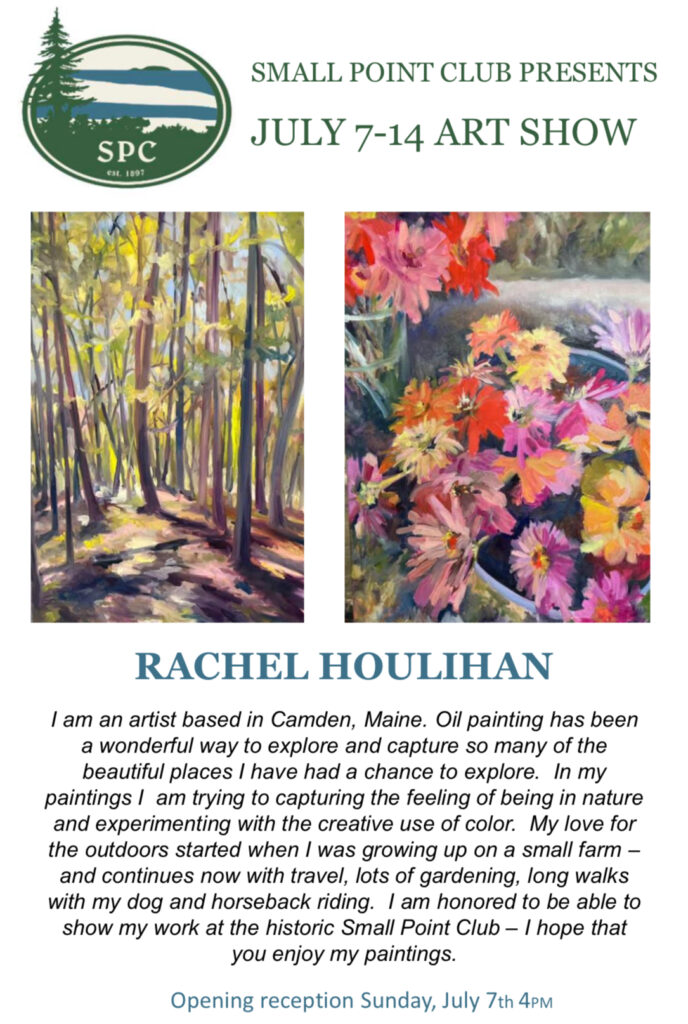

Speaking of my students, this is Rachel Houlihan from Camden:

Keep plugging

Learning to paint takes time and practice. Don’t be discouraged by initial challenges. If you focus on the product, you’ll never be satisfied, but the process of learning is sublime.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.