What is fine art?

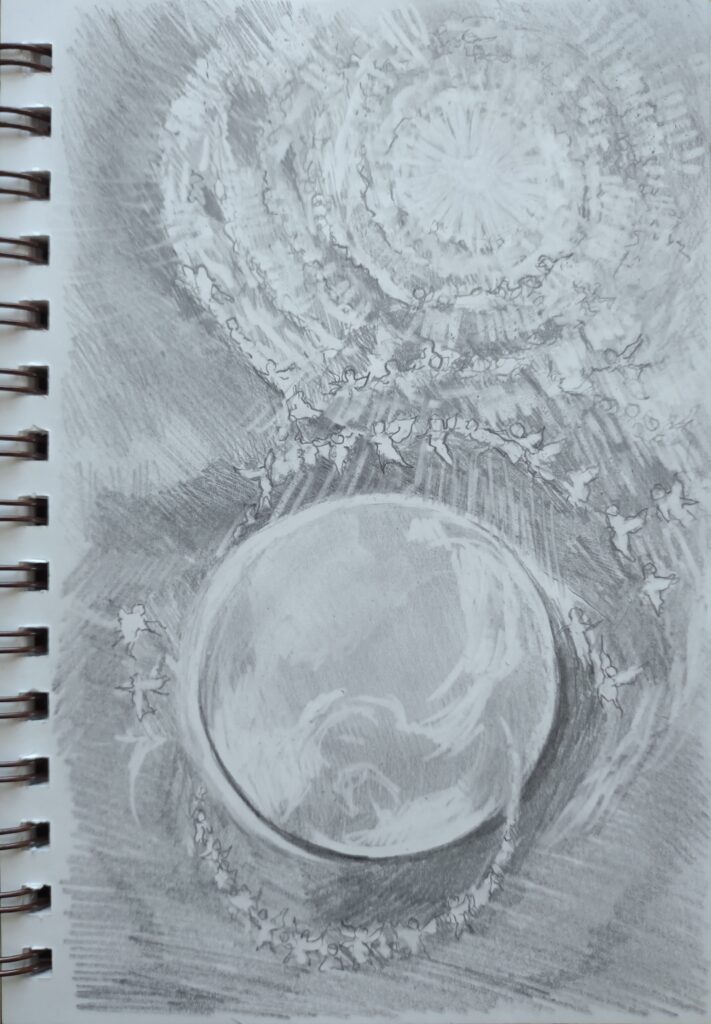

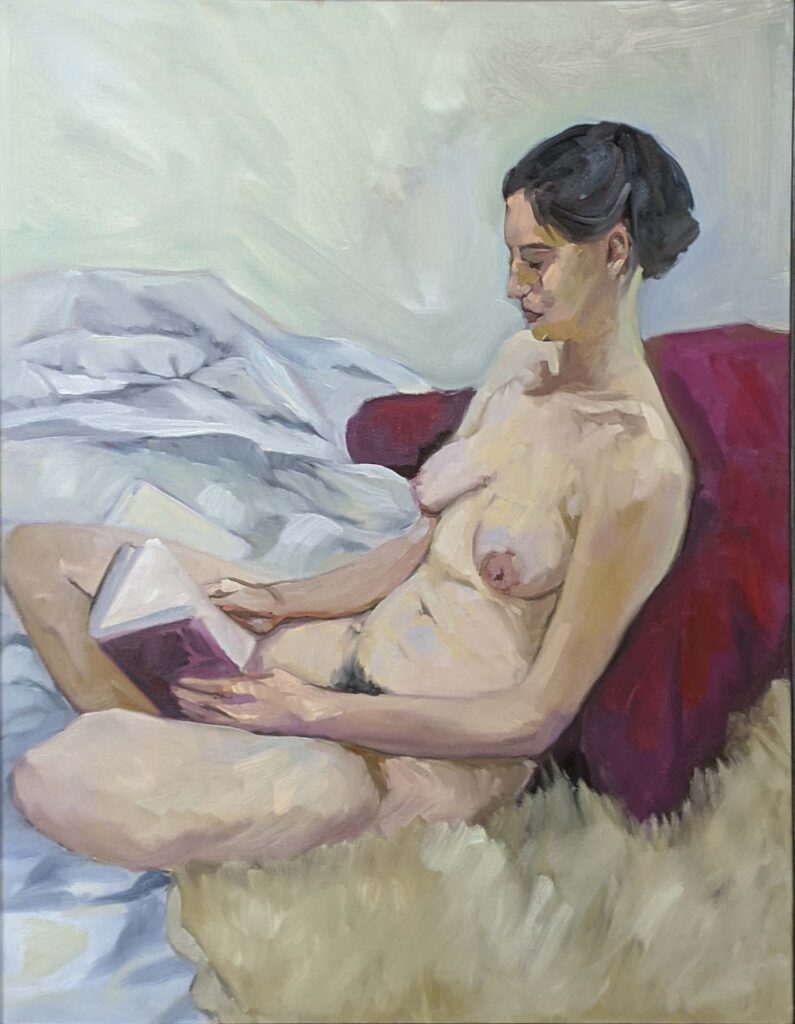

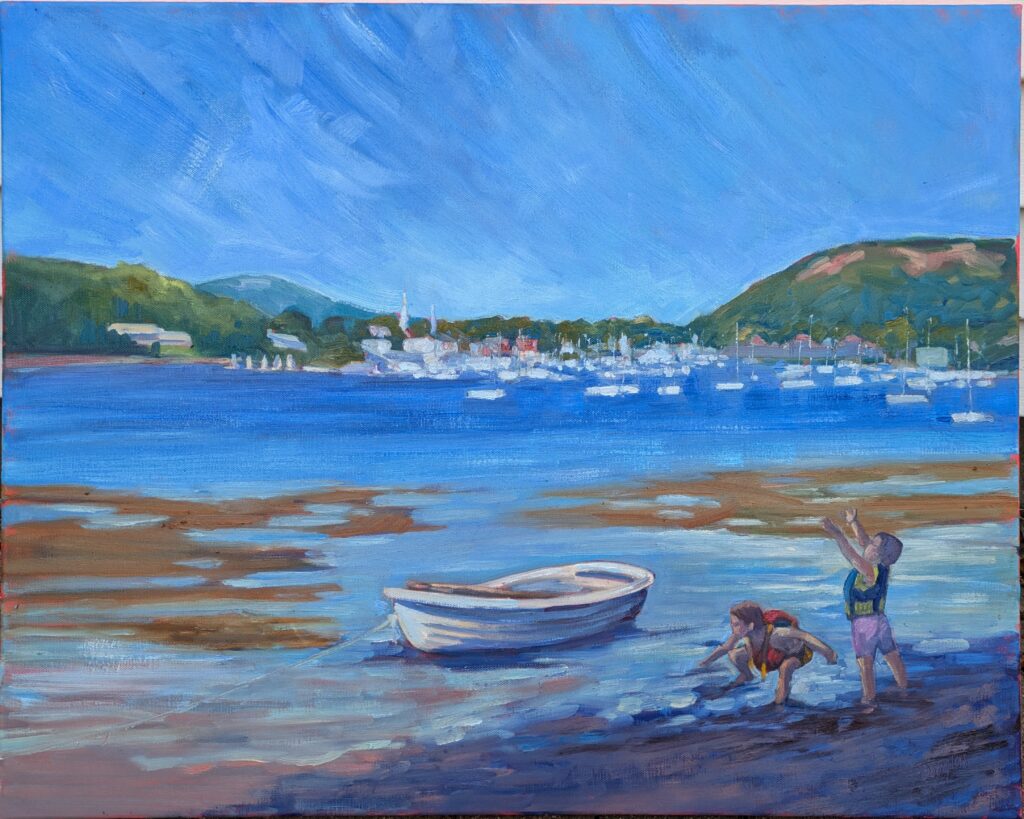

Fine art serves no practical purpose. It’s created for its aesthetic value and emotional impact rather than to do anything useful.

Calling something ‘fine art’ is not an assessment of quality. Something can be utter dreck and still fall under the heading of fine art, and fine craft is frequently better-executed than fine art.

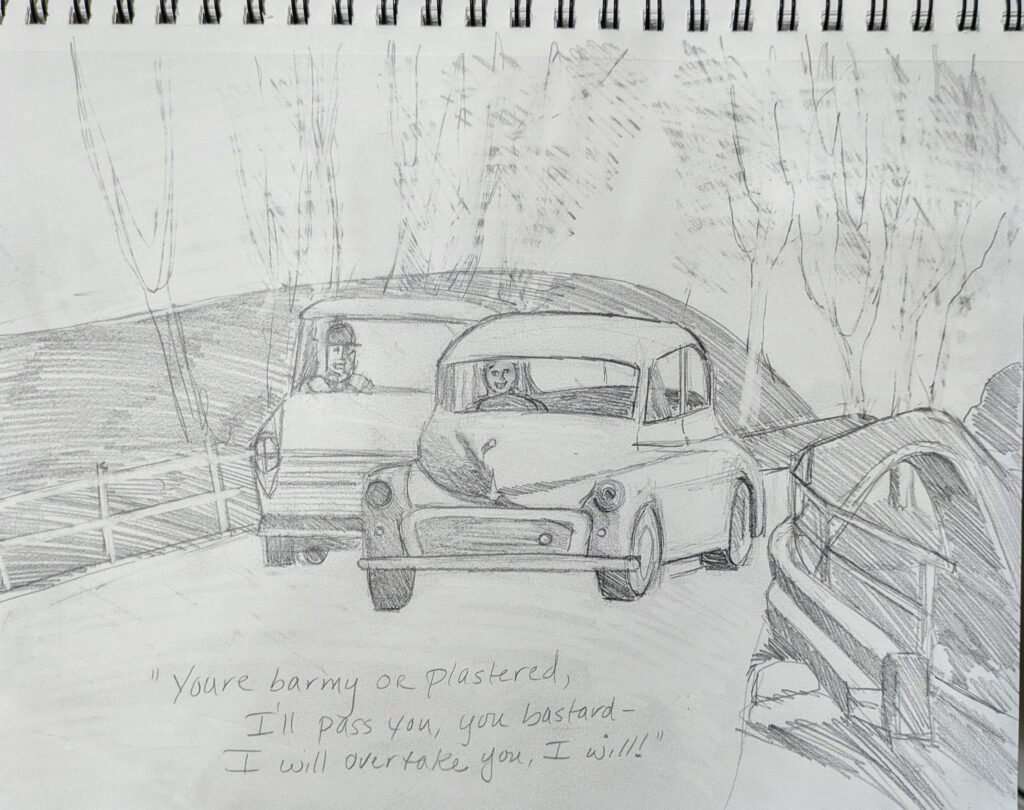

The line between fine art and other disciplines is blurry. For example, Norman Rockwell and N.C. Wyeth were primarily illustrators, but they’re also considered among the best painters of their generation. And by any narrow definition of purpose, most pre-Renaissance painters would be lumped in with illustrators, since one of their main goals was to explain and amplify the Bible. What is fine art, then, is a difficult question to answer.

What is the difference between fine art and commercial art?

The primary difference between fine art and commercial art is intent.

While fine and commercial art are both tools of communication, fine art’s focus is emotional, visual, and intellectual. Commercial art is made to sell a product, service, or idea. It is functional.

Fine art generally seeks to speak to its audience one-on-one, whereas commercial art is directed towards markets.

Fine art is judged on creativity, expression, technical skill, and its intellectual underpinnings. The individual artist and his or her vision is paramount. That means fine artists have the freedom to produce work that nobody cares about (although that’s likely to result in penury) whereas commercial artists generally work under another person’s guidelines and requirements.

Do fine art and commercial art use the same media?

There is no distinction between what is used in fine art and what is used in commercial art, although certain media (for example oil painting or lost wax casting) are more suited towards fine art. Other media (for example, neon or digital imaging) are more suited toward commercial art.

What is the difference between fine art and fine craft?

The line between fine art and fine craft is even squishier. Traditionally, fine craft creates functional objects, although that has never been absolute. Grinling Gibbons was Britain’s most celebrated woodcarver. He was an excellent businessman and much of his work falls firmly in the area of fine craft. However, he also produced amazing confections in lime wood that transcend any purpose.

Since both fine art and fine craft can create decorative objects, the distinction is usually a matter of focus. Fine craft is said to emphasize skill and technique, whereas fine art emphasizes ideas.

The most comfortable distinction is in media. Fine craft includes ceramics, glasswork, textiles, woodworking, goldsmithing and other disciplines where the materials are critical to the results.

Which is best?

Since the 18th century, critics and gallerists have tried to rebrand fine art as an intellectual discipline, (although its practitioners generally remain stubbornly practical). Because of this, fine craft, illustration and commercial art have been perceived as lower art forms. This is an absurd distinction, and one that has led us to the worst excesses of conceptual art.

I’ve been both a commercial and fine artist, and I pursue some crafts. None is inherently better than another; it’s all a question of what you’re called to do.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

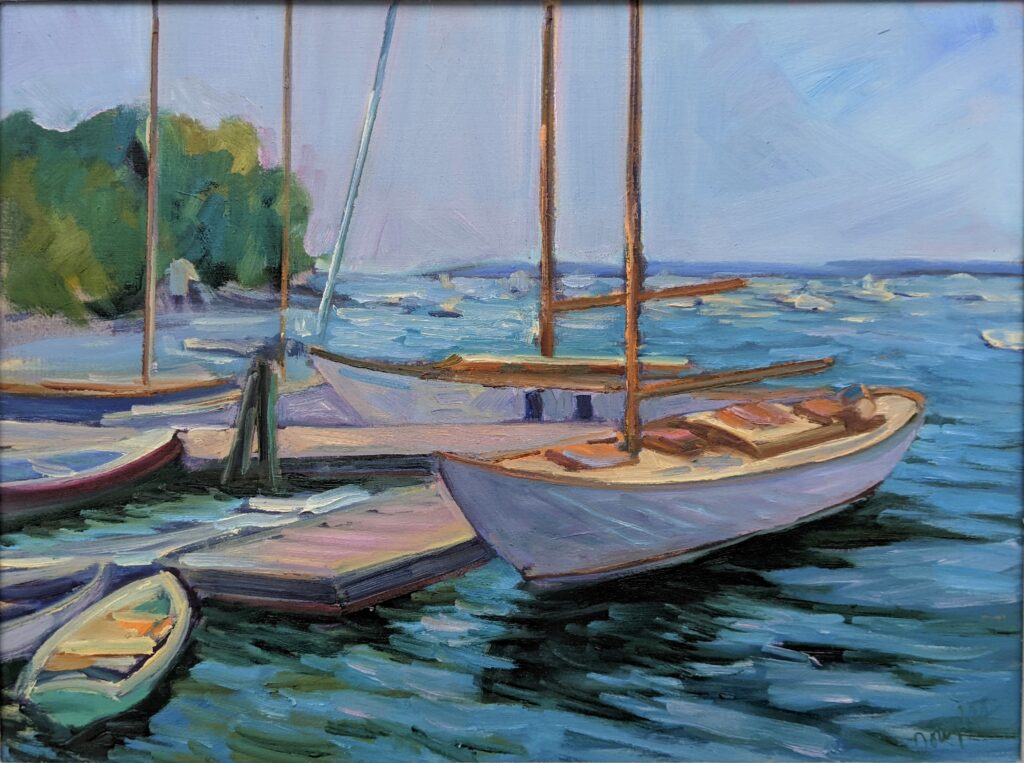

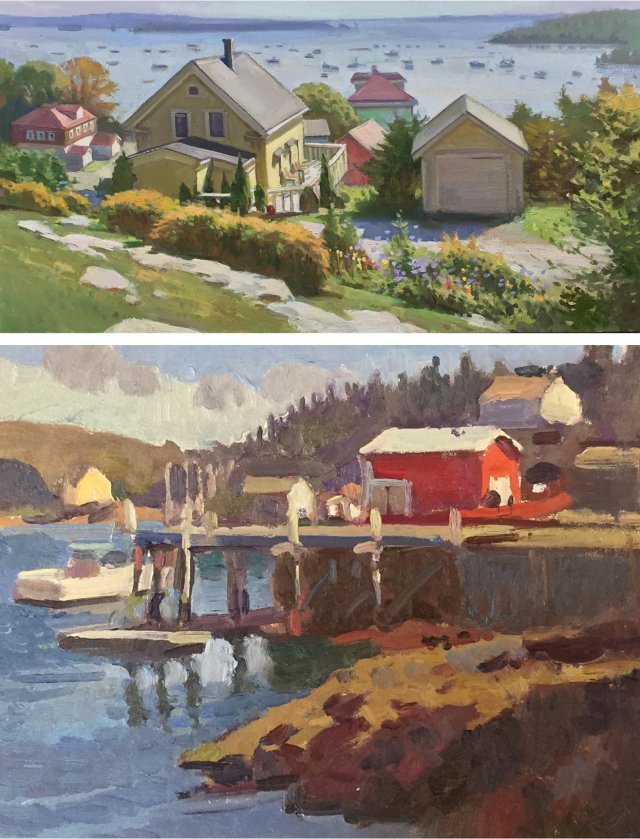

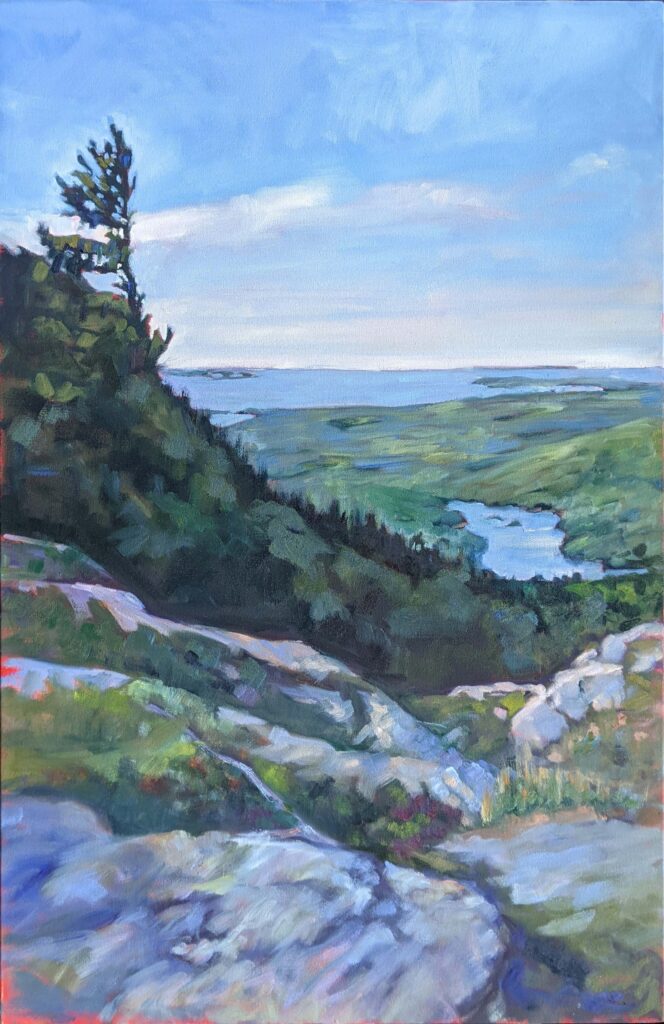

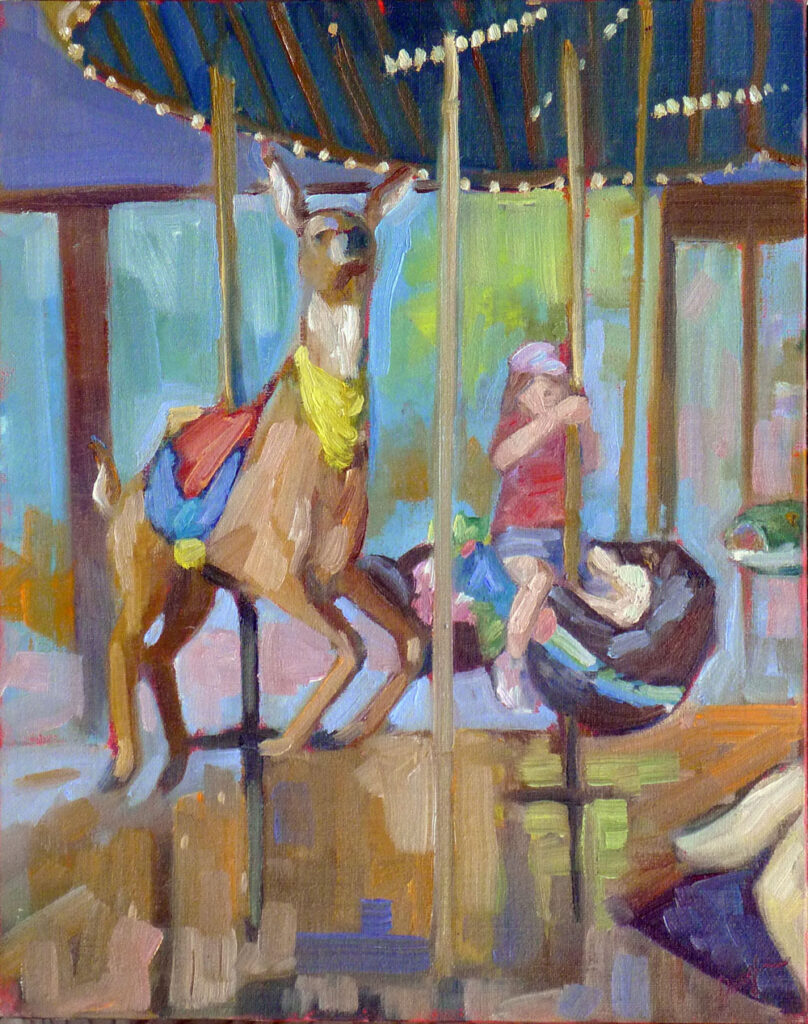

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.