“Can you give me information on lighting for artists, especially lights that work well for watercolor painting?” asked my friend and sometimes-student. “I have a new table setup in a permanent spot now, but it doesn’t have much direct or indirect light from the windows in that room (they are under our deck on the east side of the house) and I am looking to purchase a light that will give me good natural lighting to paint by.”

It’s a pity she doesn’t have natural daylight, since it is the standard by which all studio light is measured. But we all sometimes need to work in less-than-optimal conditions.

The evolution of gallery and studio light

I’ll spare you the candle and gaslight, which were mostly obsolete by my childhood. Besides them, I’ve had incandescent, compact and regular fluorescent and LEDs (Light Emitting Diode) in my studio and gallery spaces.

Fluorescent lights are now illegal in my state and many others. Incandescent and halogen lamps are being phased out, but are excellent light sources for color quality.

In recent years, we’ve adopted LED technology. It’s more energy-efficient, longer-lasting, and offers greater design flexibility. LEDs offer color temperature shifting and dimming potential.

LED lights are now the most common choice for most lighting applications, but that doesn’t mean they are the best for color rendering.

Switching to LEDs can lead to a reduction in color accuracy, which we express as Color Rendering Index (CRI). The higher the CRI values, the closer a light source will be to natural daylight.

Color Rendering Index and more

“Daylight” balanced bulbs are a start, but they’re not the whole story. What’s most important is the CRI, which is 100 for daylight and usually 80 for LED, which is too low for accurate color. A few years ago, the best you could get in an LED was a CRI of 85. Today you can get CRI-90 and even 95 bulbs.

The CRI number indicates how accurately a given light source renders colors in the space it illuminates. Natural white light from the sun is a combination of all colors in the visible light spectrum. It renders the colors of objects accurately. Incandescent and halogen bulbs also have a CRI of 100, because they’re also broadband.

CRI is calculated by measuring individual colors and then averaging them. However, it doesn’t include some outliers, including R9 (red) and R13 (skin tone) colors. If you’re primarily a figure painter, you might choose light sources with high R9 and R13 values, in addition to a high CRI. How do you find that information? In the tedious small print on the manufacturer’s website.

How do LEDs work?

LEDs make white light by combining red, green, and blue LEDs in the same light source or by incorporating white phosphors on a blue LED to generate white light. That isn’t a full spectrum, which means that some colors are missing in the light reflected to you.

LED technology is advancing every day, and getting closer to representing the full color spectrum in white LEDs. The LED bulbs in my gallery are CRI-90 and tunable, with five different color settings.

My gallery has conventional track lighting, but the fixtures aren’t the important issue. Just make sure you have enough fixtures so the light is more ambient than focused.

Reflected light

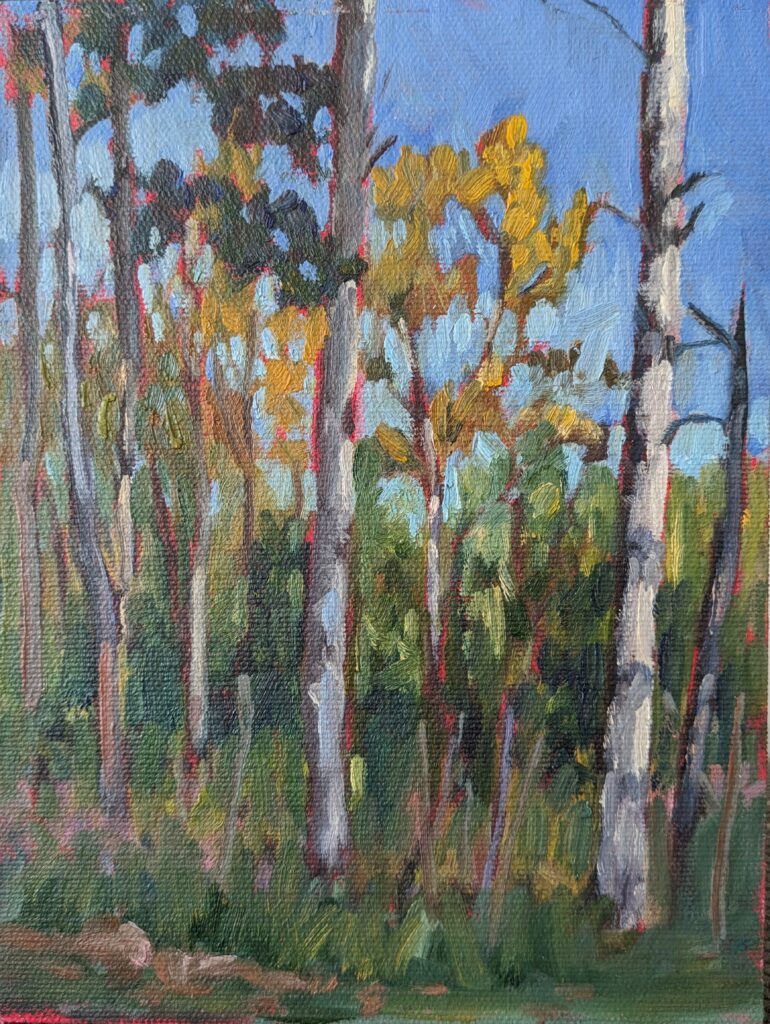

The cleanest color light can’t override brilliantly-colored walls. My studio has natural wood shiplap, it makes everything too warm. Doug doesn’t want me to repaint my studio walls white (I don’t blame him; they’re natural wood). In the daytime it’s not a problem; at night, white reflectors help.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

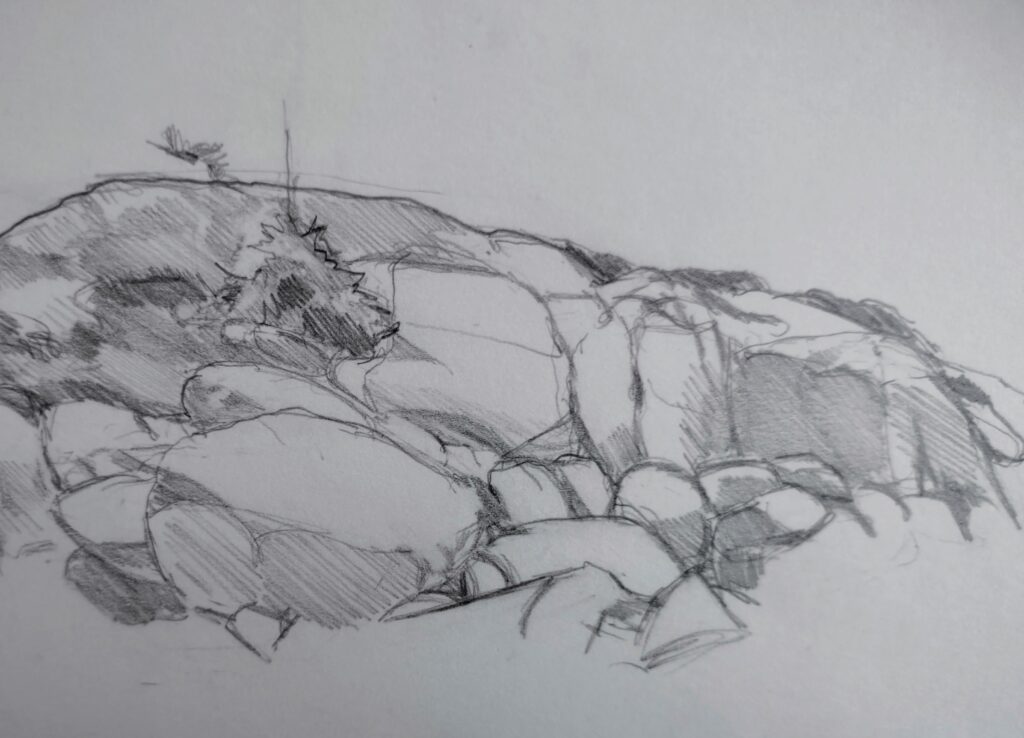

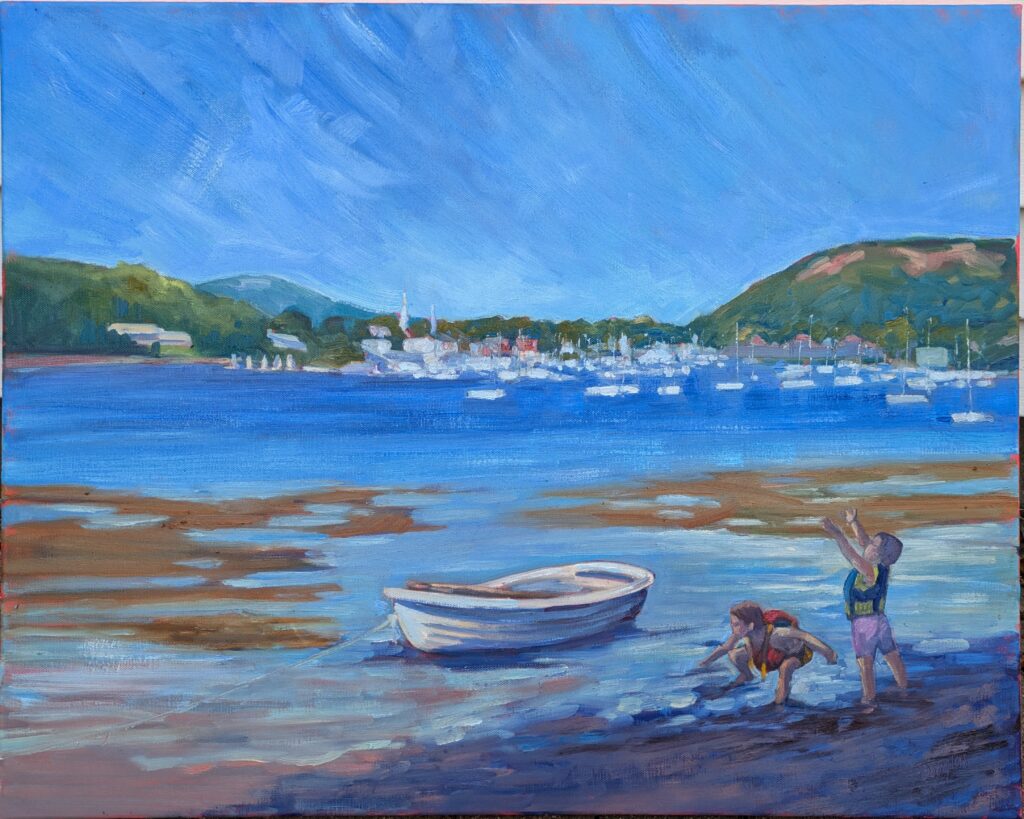

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.