I’m often asked about the best medium for the beginning artist. That’s like assuming that there’s a one-size-fits-all catsuit.

No medium is inherently easier or more difficult than another. They all have their challenges and rewards. Similarly, no medium is inherently more toxic than another; the toxicity of paint lies in the pigments, not the binder. You can avoid toxic pigments in any medium. And, perhaps most importantly, once you get past the entry-level supplies, they all hit an expense plateau, so you might as well choose what you like.

But don’t be surprised if you end up working in more than one medium. I use them all, and my great regret is that I don’t have more time to experiment.

Acrylics are fast-drying and versatile. You can layer and finish paintings quickly. They clean up well with soap and water, and inexpensive acrylic paints are available at most department stores at a low price (although you get what you pay for).

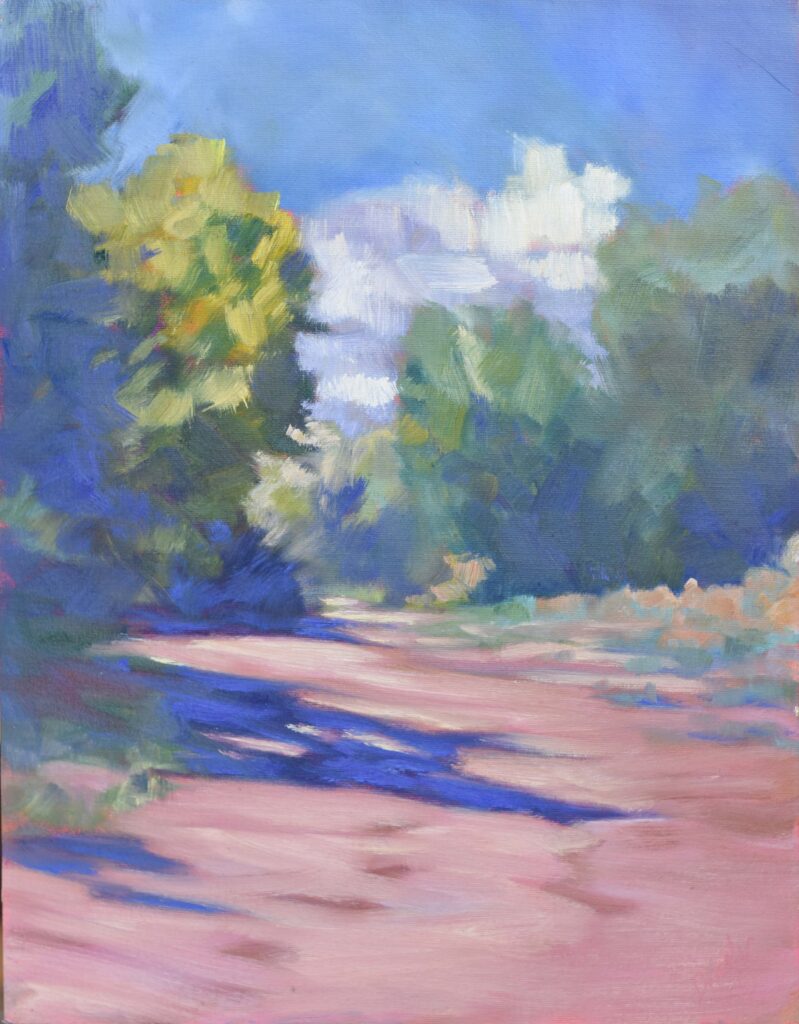

That same quick-drying characteristic is a minus when it comes to working slowly or en plein air, which is why most manufacturers now offer retarders. Retarders help, but never give you the open time of oils. Acrylics can also darken as they dry, and their final feel is more plasticky and less buttery than oils.

You can work acrylics leanly, but adding too much water breaks down the bonds. If your goal is transparency, you need to use an acrylic medium designed for glazing.

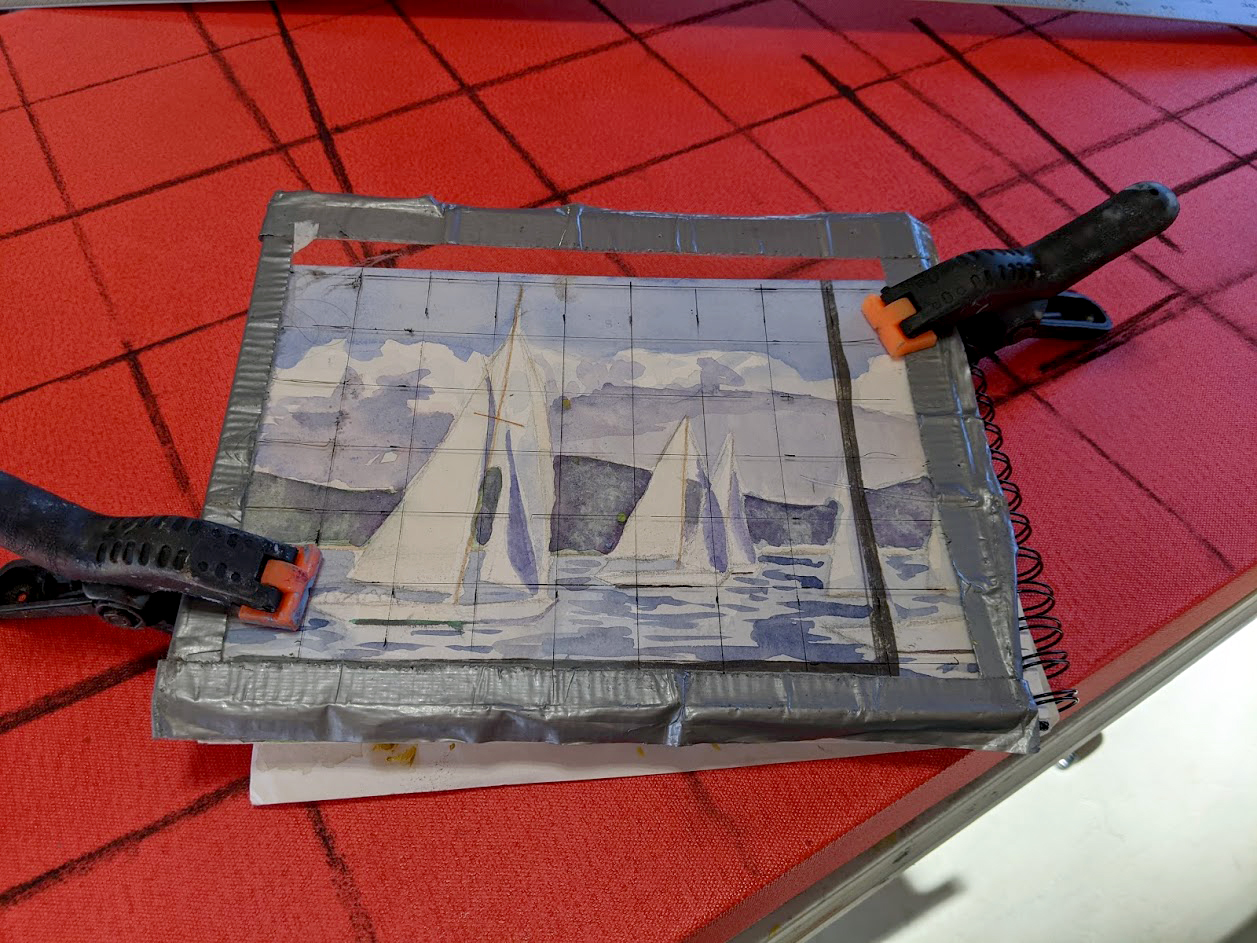

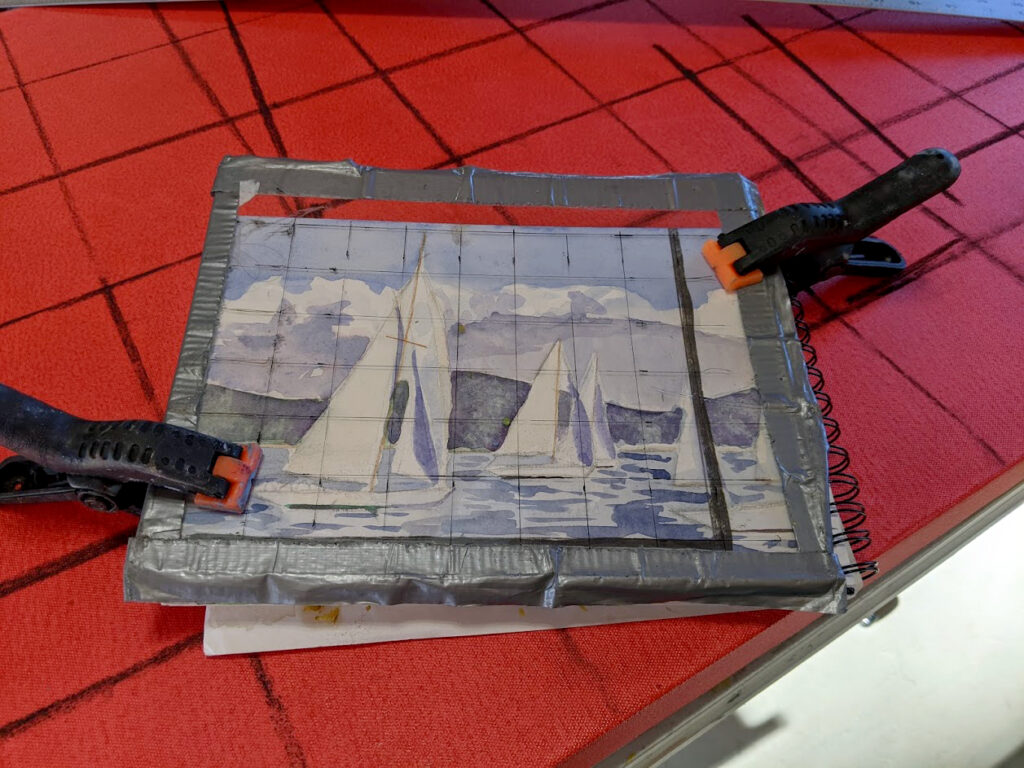

Watercolors are the most portable medium. With a travel kit, a brush and a sketchbook, you can paint anywhere.

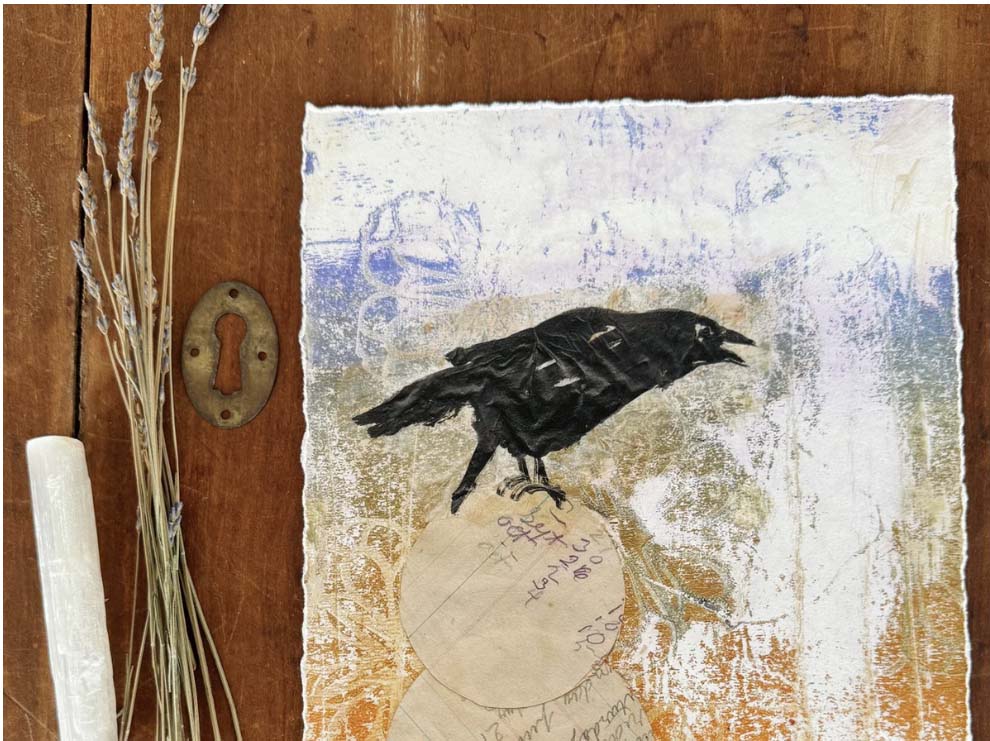

Watercolors have a luminous quality that comes from the paper reflecting back through the pigment. They’re fast and spontaneous, and you needn’t worry overmuch if you screw something up; just paint something else. Cleanup is, of course, absurdly simple. Just rinse your brushes, wipe off your palette, and head home.

Of course, that’s all true until you set out to create something brilliant. The downside of watercolor is that errors are hard to fix. Once pigment sets, it’s often there to stay. That means you need to plan ahead. And getting consistent results takes practice and patience.

And good watercolor paper ain’t cheap, as my friend Becky constantly reminds me.

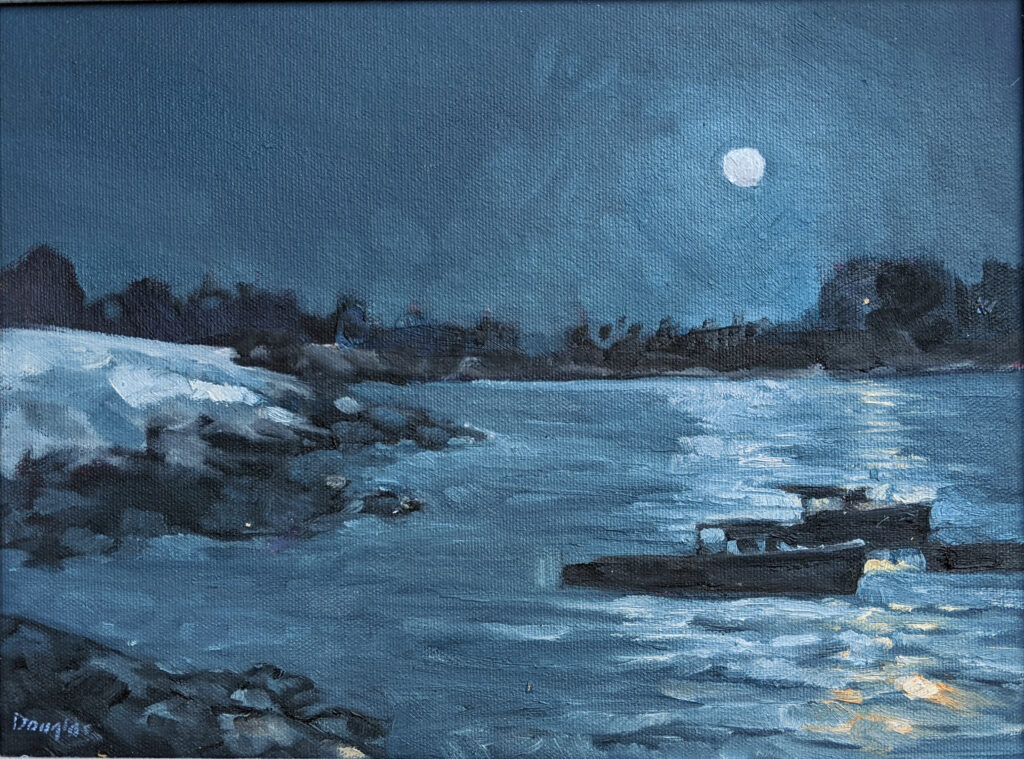

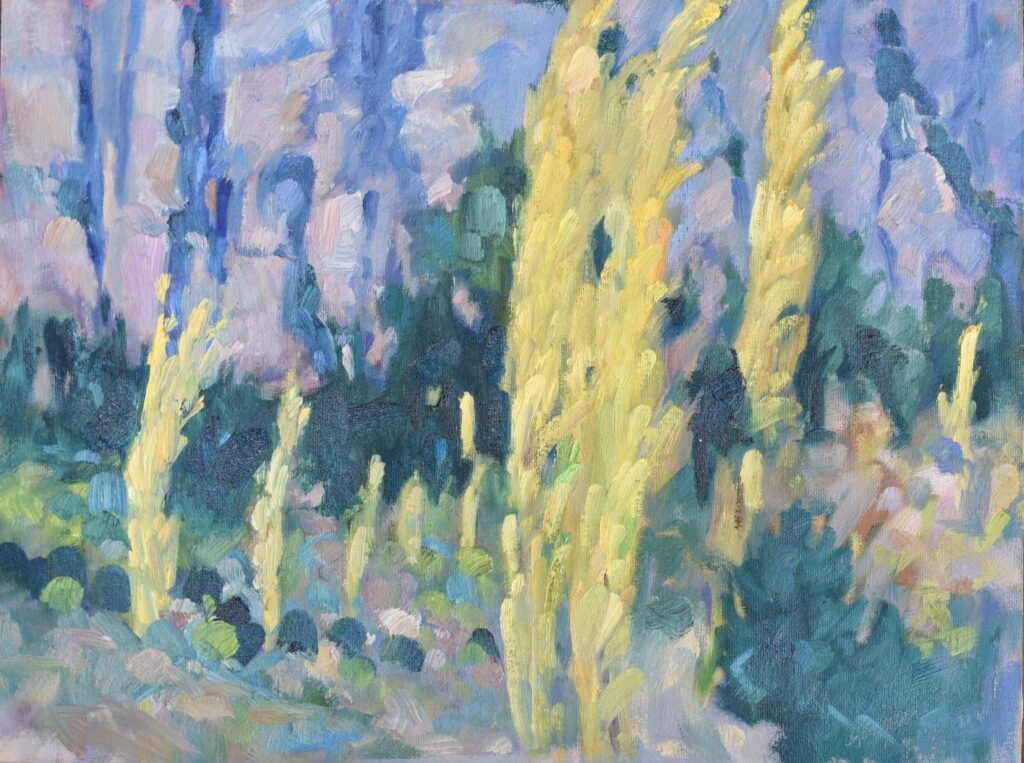

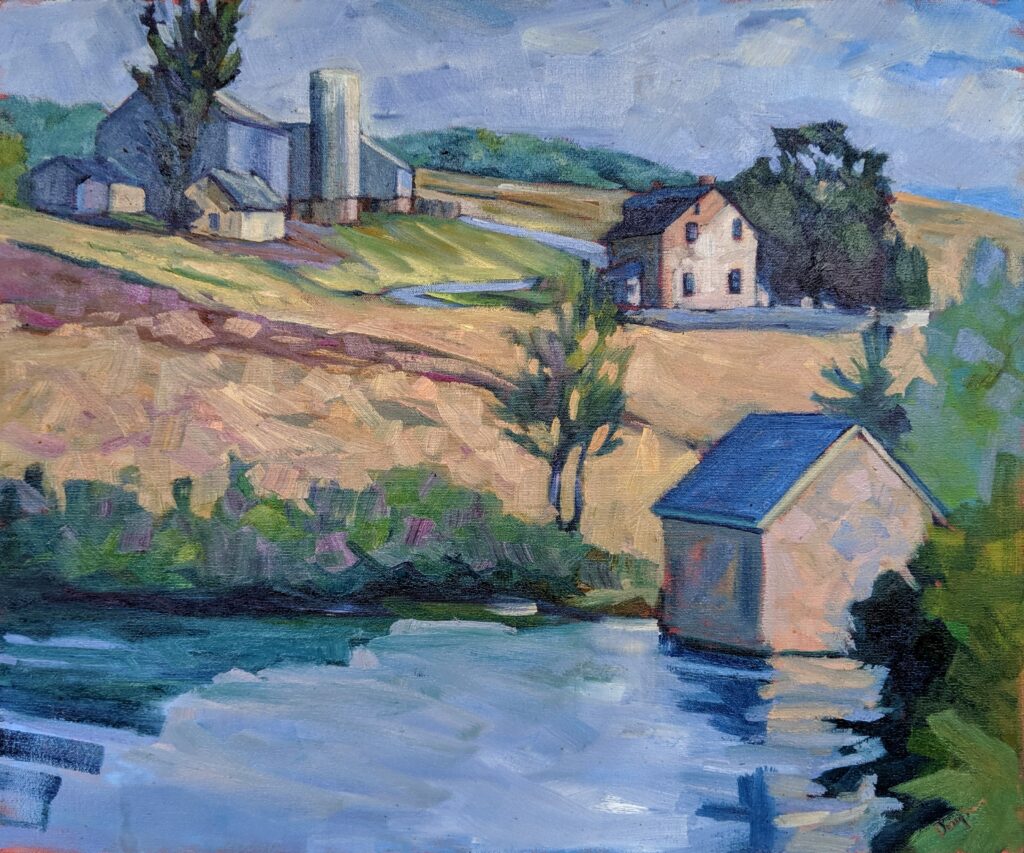

Oils offer the richest, most vibrant colors. Since they dry very slowly, you have tons of time to work, blend, tweak, and perfect your transitions, if that’s your thing. Oils have a centuries-long track record for durability without fading, and you can go from thin glazes to thick impasto with the same material.

Oils can take anywhere from a few hours to a few days to dry to the touch, but don’t be fooled; that painting is still wet inside, which is why it can’t be varnished immediately. You will need odorless mineral spirits and a good brush soap to clean your brushes. The cleanup is a bit finickier than with other mediums, but it needn’t ruin your life.

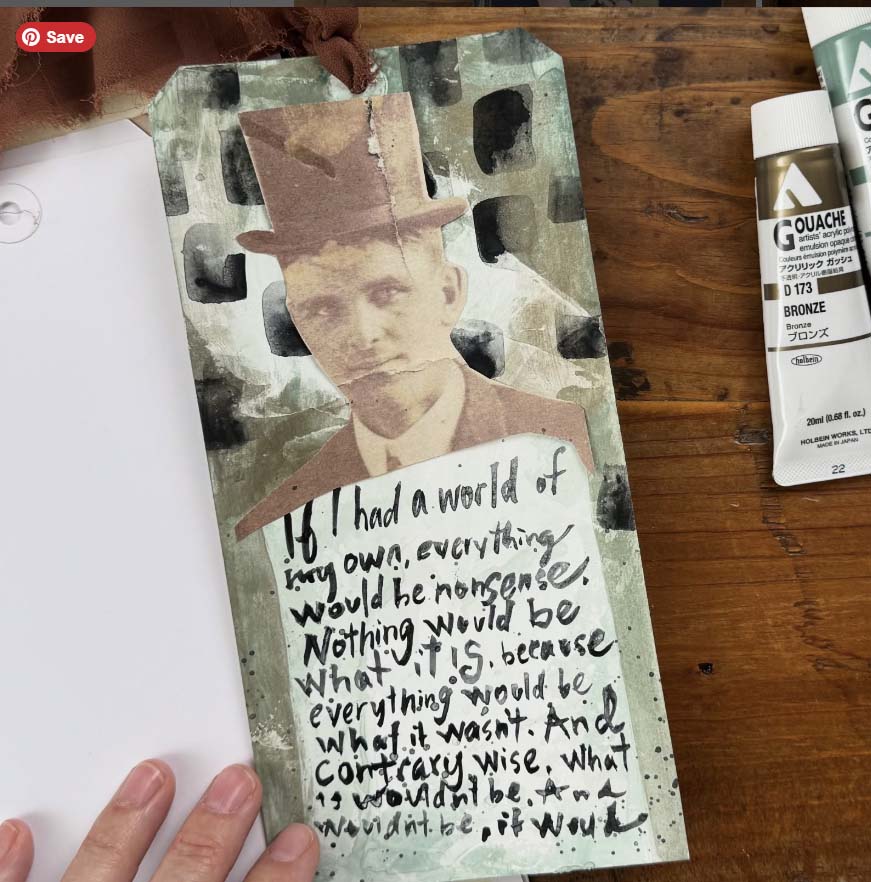

Gouache is just opaque watercolor. It dries to a matte finish, and can cover underlying layers. It’s reworkable and fast-drying. It’s an excellent learning medium and is often used by illustrators because it’s quick.

Once dry, the paint layer can be easily scuffed or reactivated by moisture, so varnishing can tricky. Colors don’t always dry accurately, and gouache doesn’t blend well.

You need to work on a stiff board or paper, because gouache will crack if laid down too thickly or not on a proper support.

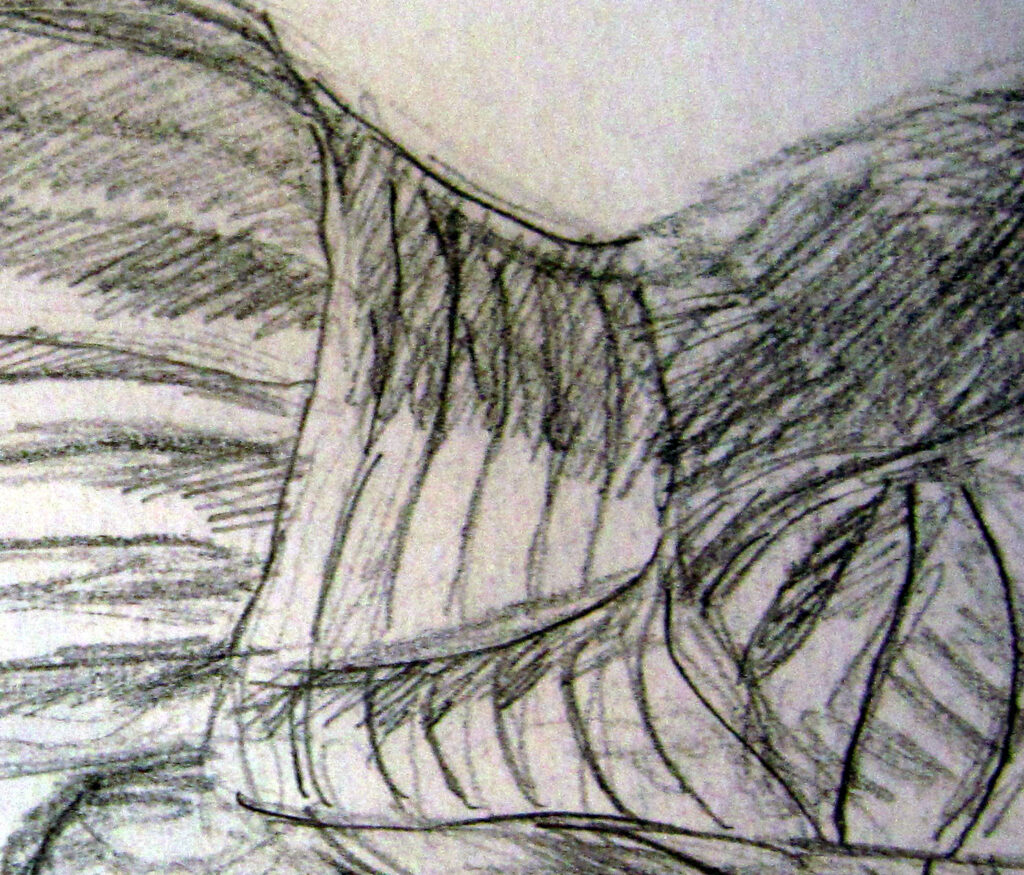

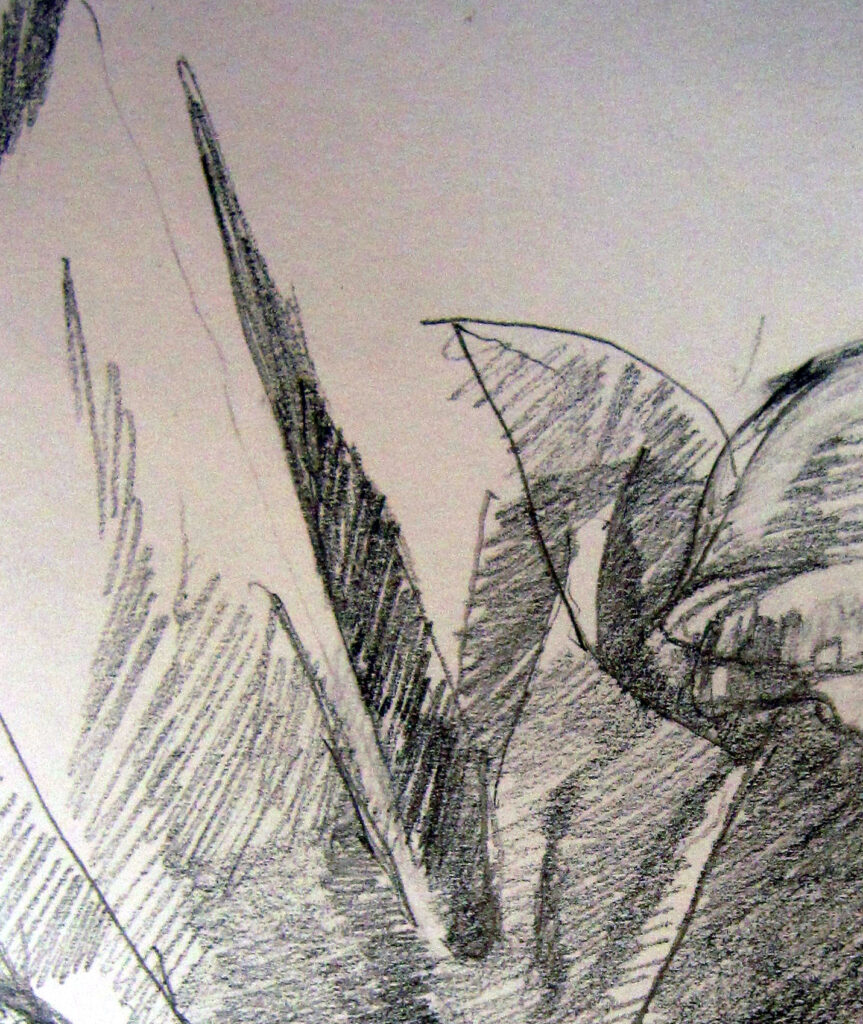

Pastels are expressive and tactile and support a wide range of styles.

There’s no need to learn brushwork with pastels, since there aren’t any brushes. Blending is simple and intuitive, as is layering and creating texture. Pastels, like oil paints, have a good record of longevity.

Finished pastel paintings are fragile, and need to be framed or fixed (which may change the colors.) Pastel dust is also potentially hazardous; more so, in fact, than any paint-bound medium. So pastelists should work in well-ventilated areas and wear some kind of gloves, since pigments can be absorbed through the skin.

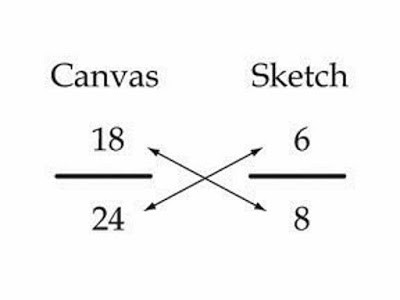

My Tuesday class is sold out, but there’s still room in the Monday evening class:

Zoom Class: Advance your painting skills

Mondays, 6 PM – 9 PM EST

April 28 to June 9

Advance your skills in oils, watercolor, gouache, acrylics and pastels with guided exercises in design, composition and execution.

This Zoom class not only has tailored instruction, it provides a supportive community where students share work and get positive feedback in an encouraging and collaborative space.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

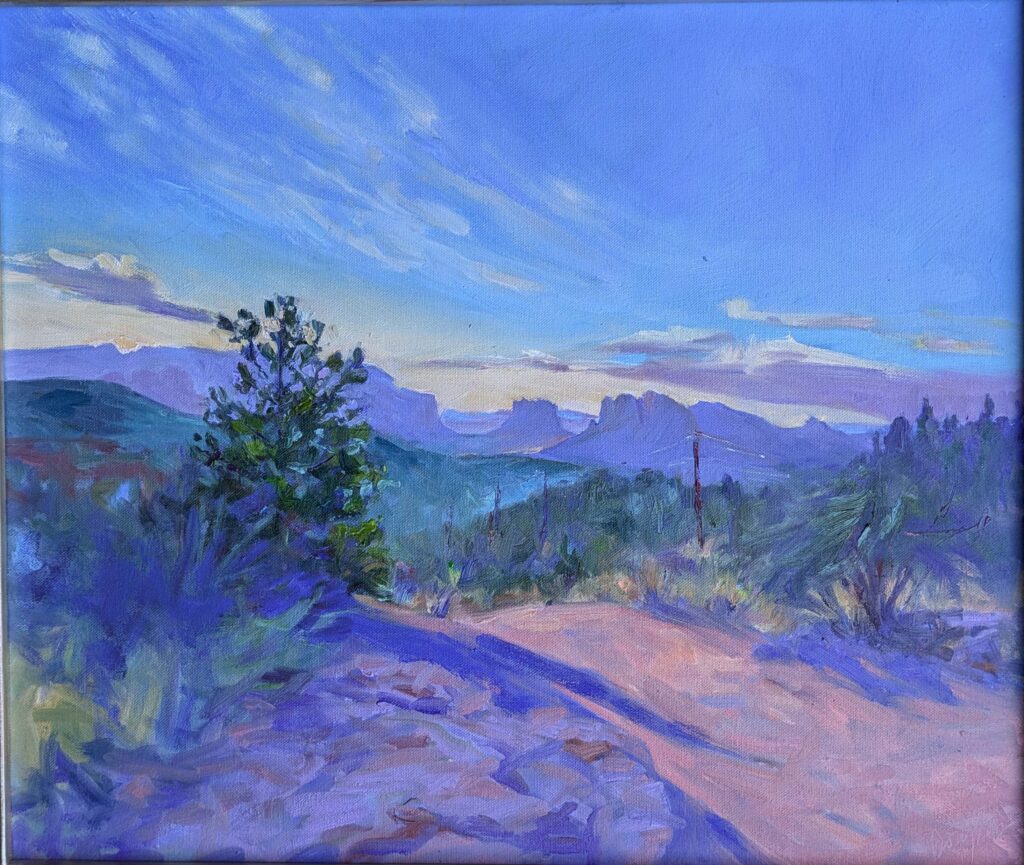

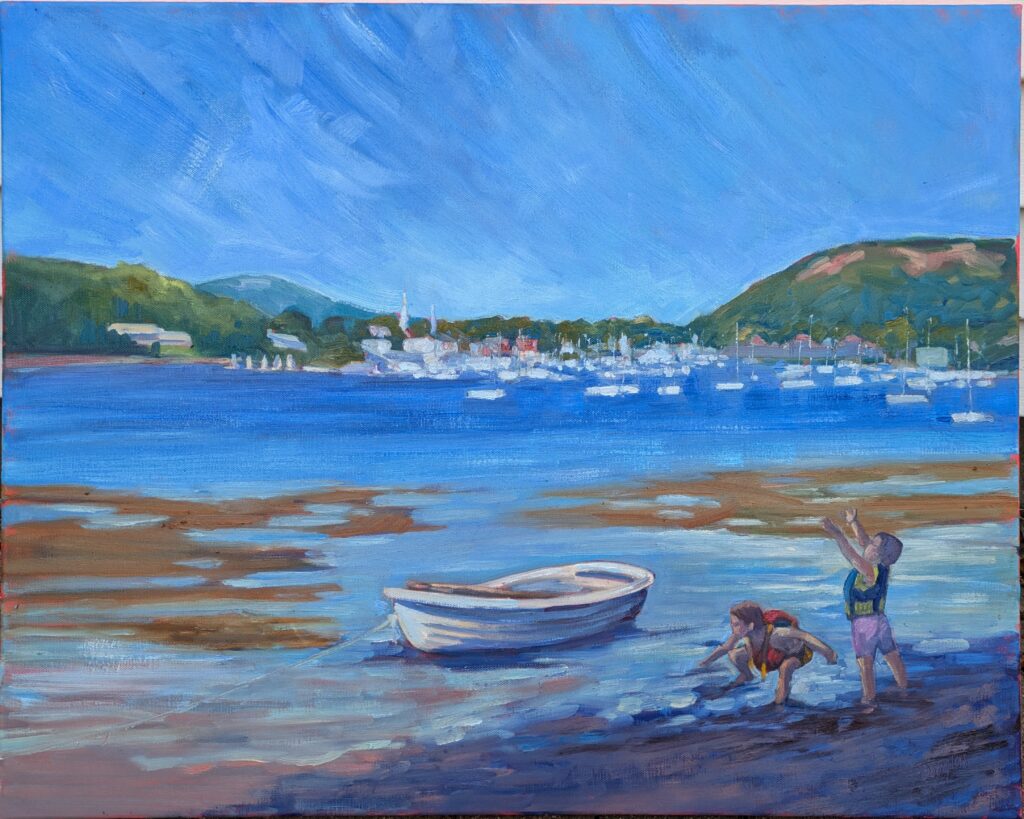

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.