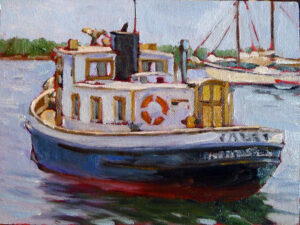

“I noticed a boat just off the pier where I was sitting,” pastor Tommy Faulk told us. “As I sat there and watched, I realized there were parts of the boat I hadn’t noticed in my first look. The boat was drifting around the point where it was anchored, making every side visible.”

Tommy was making a point about our limited human perspective, but it’s something that everyone who draws boats has noticed. When I asked him if I could quote him, he laughed and told me that it came from a drawing exercise he did on a wilderness trip with Mountain Gateway.

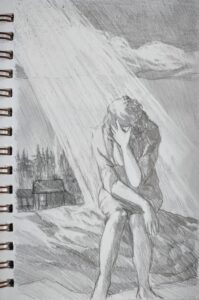

That didn’t really surprise me. There are several art school variations of this exercise. My favorite was one I did with the late Nicki Orbach at the Art Students League. Our goal was to ‘see’ right through the figure to imagine what it looked like from the other side. For example, if you were facing the figure’s front, you’d try to interpolate what the back would look like, drawing on your knowledge of anatomy. If you were mindful of the shape of the trapezius from the back, you weren’t likely to ignore their influence on the front of the neck.

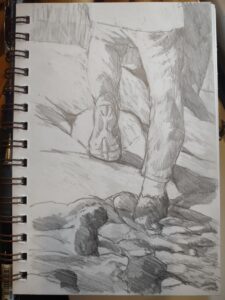

More typically, art students might draw the model from every position in a circle, moving around the room in ten-minute increments. Or, they might draw figures dancing to music. These are all exercises designed to help the student think of the human form as three-dimensional, rather than as a two-dimensional cutout.

You don’t need to be in a figure class to do these exercises-you can them with still life or objects in the landscape. They will expand both your imagination and your sense of three-dimensional space and form.

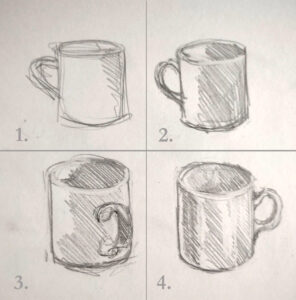

They’ll also improve your attention to detail and your visual memory. Here’s a simple exercise: imagine any object you handle regularly. Without looking at it, draw it from memory. Plop it in front of you and draw it from two different angles, each time for just one minute. Set it aside and draw it from memory again.

Your second memory-drawing will be far more accurate than your first one. And that memory lasts. How long? The more you exercise your visual memory, the better, longer and more specific your recall will be. The more you draw a specific object, the easier it is to draw it accurately from memory.

Perceived vs. real form

What you imagine the form to be before you ever start drawing is its perceived form. That’s never exactly what it looks like. When you start to examine the object through exhaustive drawing from all sides, you come closer and closer to understanding its true form.

Human perception is subjective. Camera perception isn’t subjective, but it is distorted by technical limitations. Within reason, though, your camera can be a useful guide in checking how accurately you draw. Compare a photo of the subject to your drawing, side by side. Just be aware that your camera can be as much of a liar as you are. Especially with cell-phone photography, there will be fish-eye and wide-angle distortion and exaggerated contrast. You’re best off photographing the object from a moderate distance to eliminate the worst lens distortion.

Drawing from photos

Note that I say nothing about drawing from photographs. There are times it’s necessary, but a photo has already been compressed to two dimensions. You will learn little or nothing about three-dimensional form from copying it. Drawing from photos is a crutch, and you’ll feel so much freer when you stop doing it.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.