“I have a roll of cotton duck kicking around here,” B— asked. “Can I just duct tape a big piece of that to a piece of plywood and put a few coats of acrylic gesso on it? Should I leave a few inches raw around the edge in case it comes out decent, so I can mount it on a stretcher?”

B— needs to know whether her fabric is unshrunk and unsized, or loomstate. Standard sewing fabric won't work. The gesso is meant to shrink the fabric into tautness. Duct tape isn’t designed for that strong pulling stress and will leave a sticky residue. Instead, use staples. Stretcher frames are designed for this process, so it's easiest to stretch canvas on them, although it can be done over plywood.

She could also buy already-primed linen or canvas. This is easily stapled or taped to a board because the shrinking is done. This is especially handy for class assignments or practicing chip shots.

It’s generally cheaper to buy small canvases and canvasboards than make them yourself. Only when you get to larger sizes, or you want to paint on linen, does DIY becomes a practical option.

Stretcher bars are designed to float with atmospheric changes, hence the little wooden “keys” that come with them. There is no benefit in locking down the corners by screwing them together. When it shrinks, a big sheet of loom-state linen or canvas is going to pull the stretchers into compliance. That’s why the grain matters.

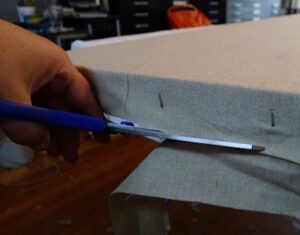

The weft in fabric (horizontal threads) isn’t always perfectly perpendicular to the warp (vertical threads). The only true straight-edge in fabric is the selvage edge. You want to cut along the grain, but you can’t just assume the weft threads are perpendicular to the selvage.

If it’s out of true, fabric will bag when folded selvage-to-selvage. You can easily square it off with the help of a friend. Fold the fabric in half along the vertical. Grasping each corner firmly, tug diagonally in alternating directions. Eventually, the fabric will square off and fall true. The ends might be cockeyed; ignore them.

Although dressmakers and quilters might use water or steam in this step, you can’t. It will shrink the fabric.

Once you’re certain the fabric is squared off, fold it in quarters. The creases will be your stapling guides.

Mark each stretcher bar’s midpoint with pencil. Line the creases up with these pencil marks, and your canvas will pull tightly on the square. Your first set of staples should be across the middle of the canvas on the warp. They should be hand-tight, no tighter. Next, staple the vertical midpoints. These four staples should all be hand-tight, without cupping around the staples, and the corners of your canvas should be square. If these four staples yield a straight cross at the right tension, the rest of the canvas will line up true.

From here use canvas pliers or your hand to pull the canvas tight but not taut. Work out from the center of each side, adding one staple and then rotating the canvas. The goal isn’t to tighten the fabric as taut as you can; the goal is to tighten it as evenly as you can. Watch the fabric grain as you go; if it’s out of line, you’ve messed something up.

Applying the gesso is easy; just keep it light and even. I use a small piece of ¼” plywood as a strigil rather than a brush; it’s faster and more effective. Make sure the gesso goes around the sides of your canvas. Don’t dilute; good gesso is already the proper thickness.