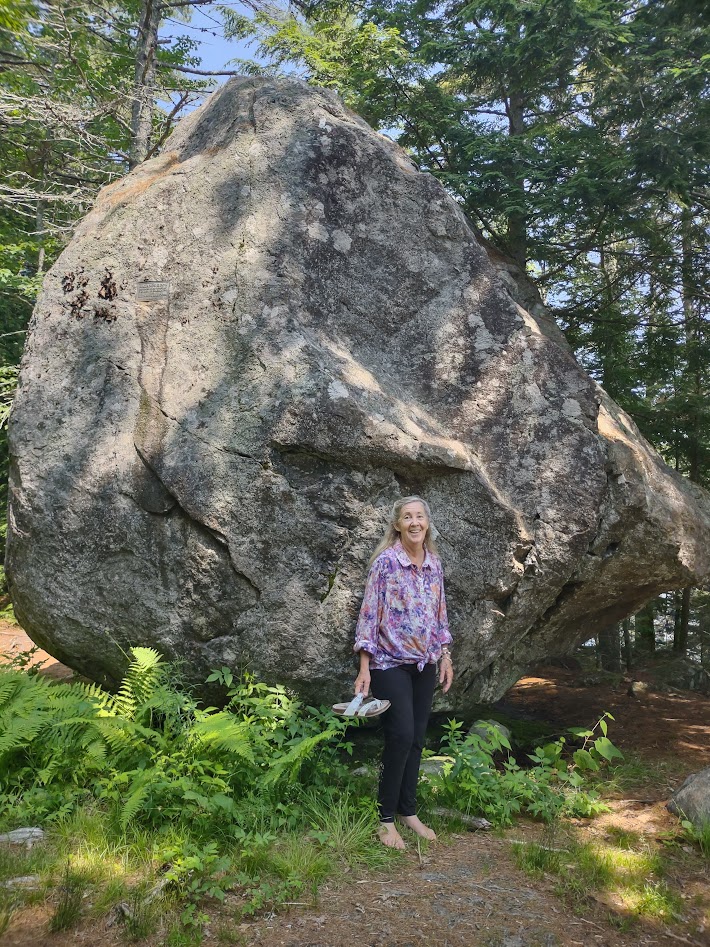

I’m thinking about Camden on Canvas and an impractical location occurs to me. It’s a glacial erratic on Fernald’s Neck. It would be long hike with a large canvas and my gear (although not nearly as onerous as painting from the top of Bald Mountain. Even when I get there, I’ll be confounded by the composition, as it’s just a huge rock by the shore. However, it’s one of those subjects that always excites me when I see it, so this might be the year I do it.

The problem of choosing plein air locations is compounded when one is teaching or organizing an outing for a group. There are practical considerations that aren’t as important when I’m painting solo.

Here’s how I approach the question:

Does the view interest and inspire? That’s a moving target, but I look for places with interesting compositions and varied elements. That way there’s something for everyone.

How’s the lighting? I consider the time of day when it’s possible to be in that location. And, of course, at midday, I generally encourage people to down brushes and rest.

Is it accessible? This is far more important for a plein air class or an event where you have spectators than it is for solo painting. However, with big canvases come big equipment, and that’s where park-and-paint can be very helpful. There’s a famous location in Schoodic that’s now off-limits to groups. I never took mine there anyway; I judged it to be just too easy to tumble off that cliff.

Is the terrain negotiable? I don’t mean just for me, but for everyone in my plein air group. The best locations are ones where the agile can move out and explore, but others can paint from near their car.

Can painters set up chairs? I have a duff back, and I no longer stand to paint. I want a place I can sit, and where my students can set up chairs if they wish. There’s no shame in sitting to paint.

What’s the weather forecast? It behooves a plein air painter to know all the overhangs, bridges, gazebos and other places he or she can shelter from the weather. That includes the sun if it’s blistering hot as it will be this week. A contingency plan is a must. In Maine, mine is my own studio as a backup location. In other areas, it can be a rented hall.

Do you have permission? I will never forget being yelled at because other painters who were not part of my group had trespassed on private property. Make sure you have permission before you go on someone else’s land. One of the hidden costs of my Schoodic workshop at Acadia National Park is the required permit (and a hidden cost for all my workshops is insurance).

Leave no trace. If you brought it in, bring it out. Police your workstation before you leave.

Are there amenities? We all need restrooms, food, and water. While I can fend for myself, I need to be clear with students about their options before we arrive. There’s no Starbucks at Schoodic, and I hope there never will be.

Can I get help in the case of an emergency? If there’s no cell-phone reception, I want to be within minutes of a ranger or a road.

Can we get away from the crowds? In Maine (and other popular destinations) that’s not always possible, but I work hard to keep people out of the worst traffic jams. Some people like talking about painting, but others really want privacy in which to work.

Are there multiple points of interest? There are many plein air painting sites with one great view, but they’re inherently less interesting than those with a variety of points of interest. Is there depth, with distinctive features in the foreground, midground and background?

I spend a lot of time scouting in the area in which I paint (and teach), usually with sketchbook in hand. You should, too.

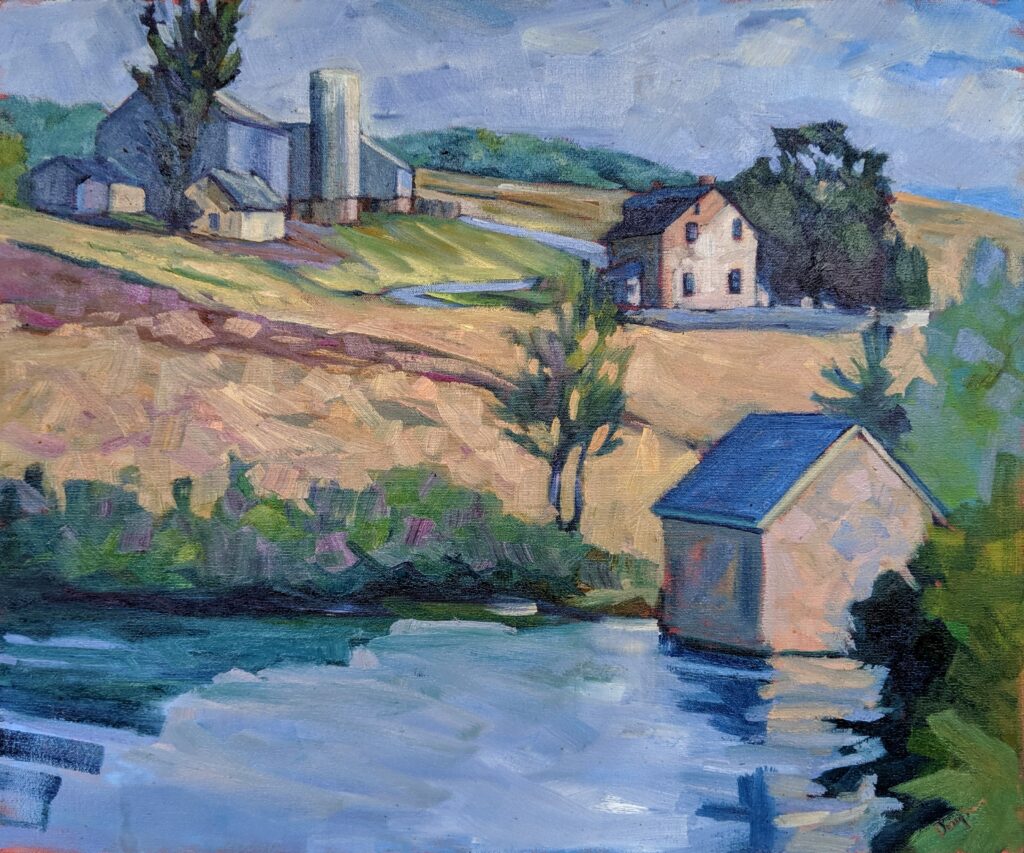

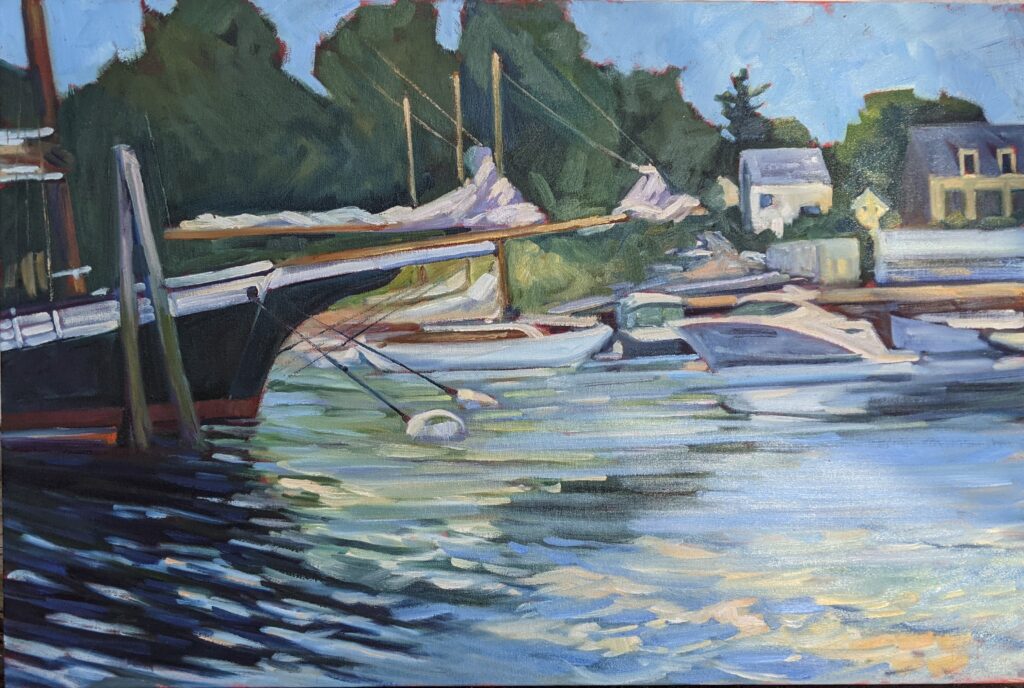

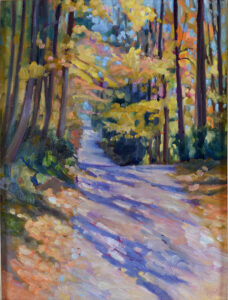

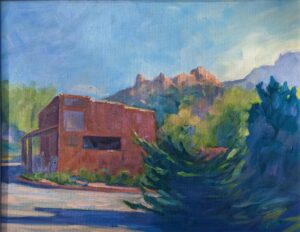

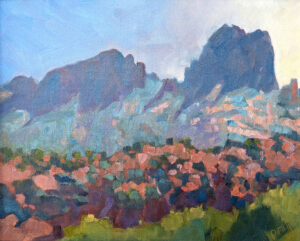

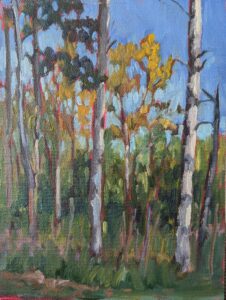

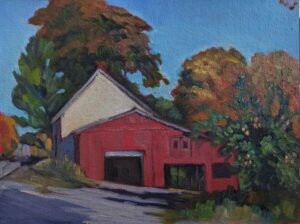

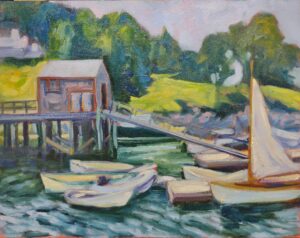

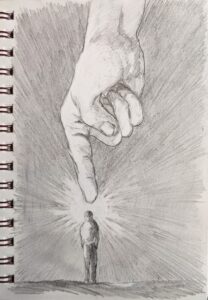

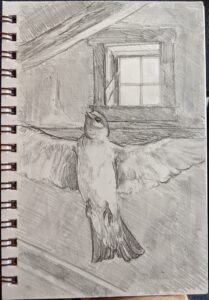

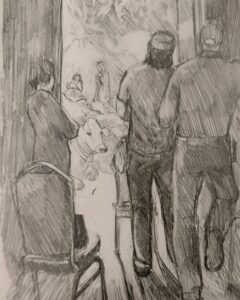

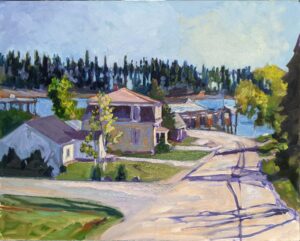

The four locations in today’s paintings are all places we’ll be painting during Painting in Paradise, here in Rockport.

Two openings this week:

Thursday, June 20, 2024, I’ll be at the Camden Art Walk, at Lone Pine Real Estate, 19 Elm Street, Camden, ME. That’s 5-7 PM, and the Art Walk is kind of a street party. It’s rather short notice, but I would love to see you there. Especially as my husband is threatening to bring his bass guitar and plunk away in the corner.

Friday, June 21, 2024, I’ll be at the Red Barn Gallery in Port Clyde, ME, from 4-7 PM for the opening reception of their first seasonal show, Barns. I’ll have three of them in the show, and my fantastically-gifted student Cassie Sano has taken my spot in the cooperative. I’m curious to see what she (and the rest of my friends there) is up to.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.