People ask me how to develop confident brushwork. The answer is to get better at drawing. Yes, confident brushwork depends in part on painting technique, but it really requires that you not flail around changing things in the painting phase.

“Draw slow, paint fast,” one of my students once said, and I’ve found it as good a motto as any for developing a loose painting style.

Confident brushwork is about simplification, and you can’t simplify when the shapes aren’t right to start with.

One painter’s testimony

Pam Otis is a painting student who’s taken my drawing class. I asked her what her biggest obstacle was. “Silencing that voice inside my head that told me I couldn’t draw,” she said. “What finally put it to rest for me was when you talked in class about the developmental stages of drawing and how adults who say they can’t draw are really just people who got to a certain developmental stage but for a myriad of reasons didn’t take it any further.

“Once I realized that it wasn’t a matter of me lacking talent or competence, just that I hadn’t learned the skills I needed to progress, it made the whole thing less mysterious and more a concrete skill that I could get better at with practice. That was truly life-changing in terms of gaining confidence in myself and my abilities as an artist.”

Most people avoid things they find difficult. “Having the technical ability to draw something correctly makes it so much easier to execute a painting without avoiding hard things,” Pam said. Drawing gives me the space I need to ask questions like ‘What would happen if I…?’”

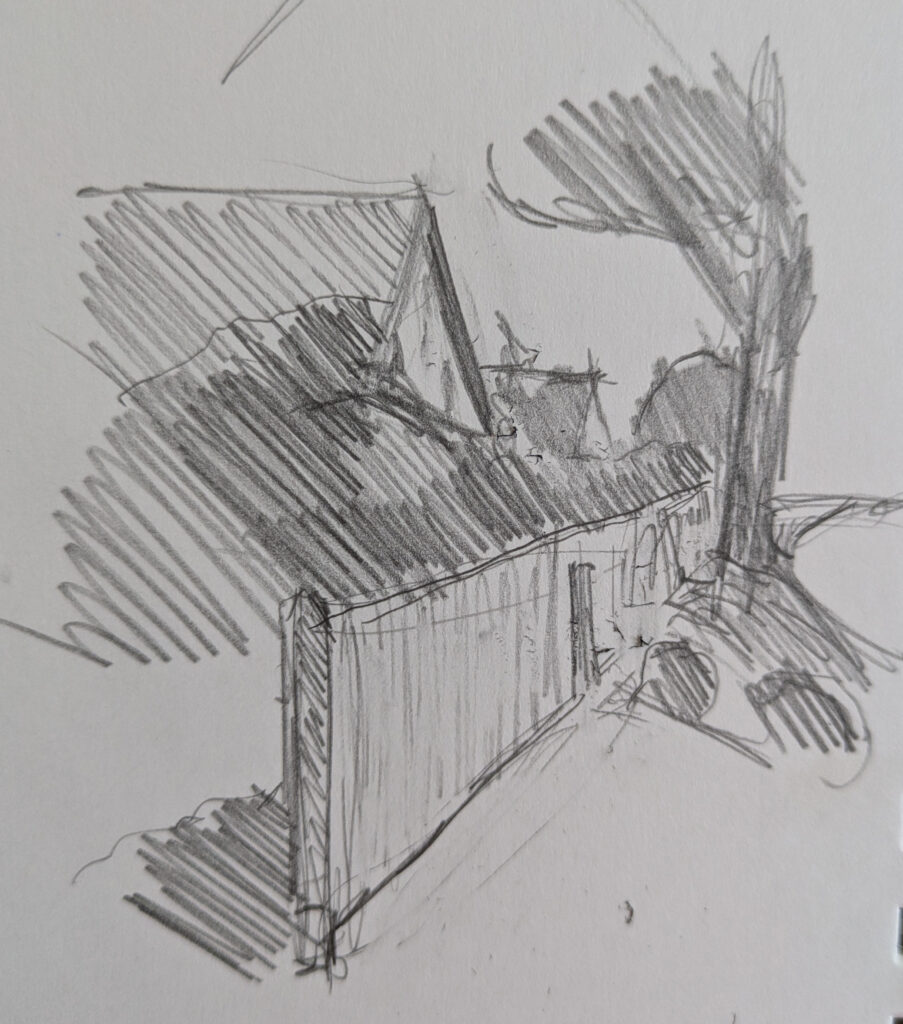

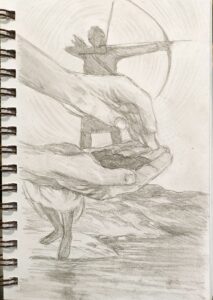

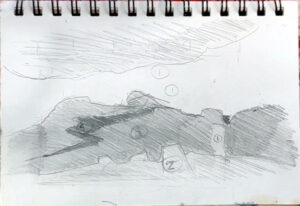

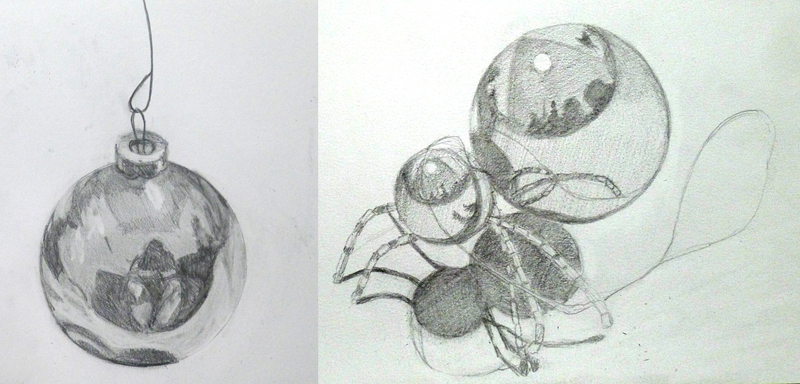

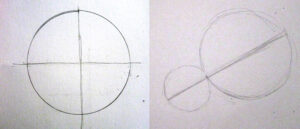

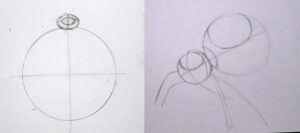

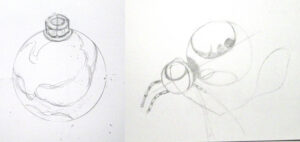

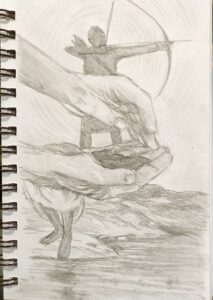

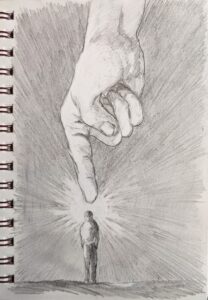

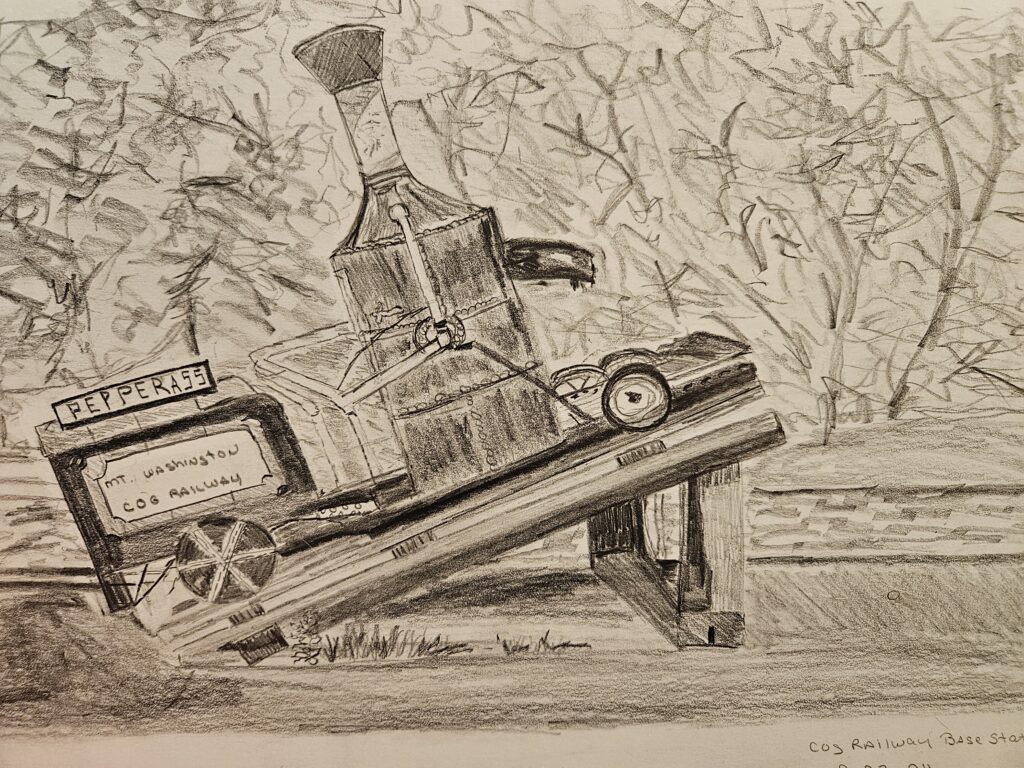

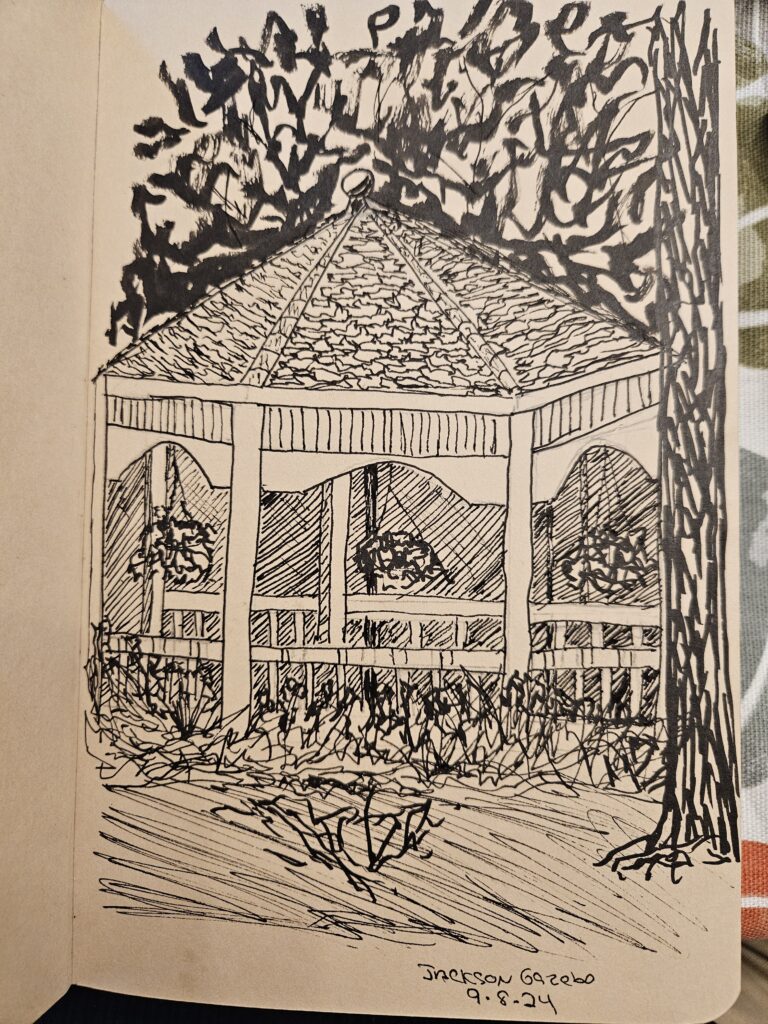

Pam says the most surprising thing about drawing is that it’s so interpretive. “There are so many ways that you can use line and shadow to tell a story, and what you leave out can often make for a more powerful image.

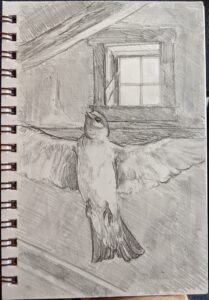

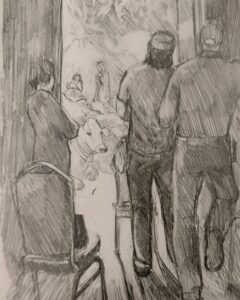

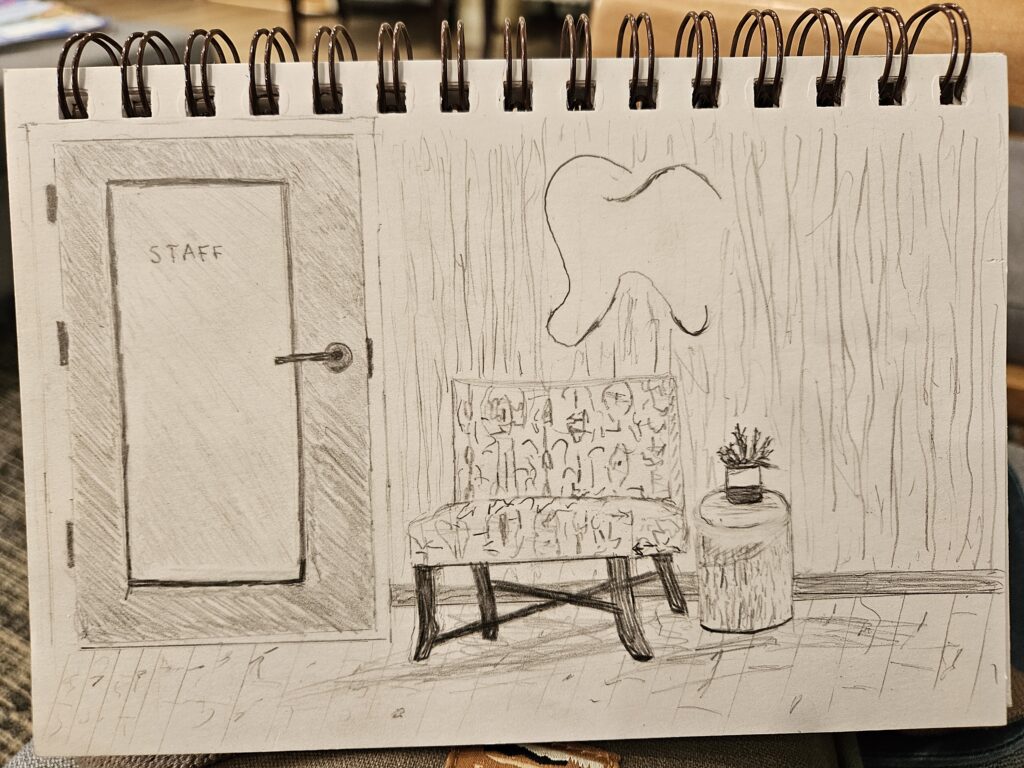

“Drawing gives me time to reflect about my goals for a piece of art, lets me play around with the details and easily make changes. One of my sketches (above) is of a waiting room. I did it on site and it was time boxed. I learned a lot from that little sketch. I redrew the chair a couple of times because I wasn’t getting the legs quite right and I wanted the cushion to be nuanced. It was like figuring out a puzzle.

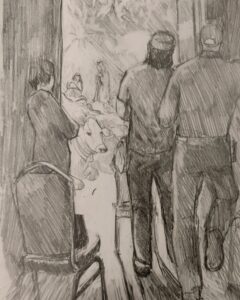

“It’s fun to spend time creating with other artists, but it’s also fun to draw out in public. This autumn we went to a busker festival and I drew some of the performers while they played and had them autograph my drawings afterwards. It was a nice ice-breaker when I was talking to them, and I had a chance to talk to some people in the audience.

“There’s still a lot of mystique around drawing, and I like to think that by taking some of my projects on the road, maybe, just maybe that’ll be the thing that inspires someone else who thought that they couldn’t draw to maybe take another try at it with fresh eyes. I’m definitely glad I did.”

If you feel your painting skills would benefit from better drawing skills, I encourage you to take my six-week drawing class starting January 6. I can promise you that your painting skills will benefit.

The best laid plans

My assistant (or boss), Laura, who’s 31 weeks pregnant, has been bunged into the hospital for the duration. That means, sadly, that the last step of my Seven Protocols for Successful Oil Painting will not be wrapped and beribboned for Black Friday. I can’t launch it without her help. It also means I’m in Albany for some unspecified time, since someone needs to rassle the four-year-old while his dad’s at work.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

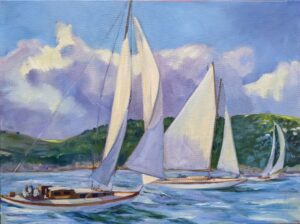

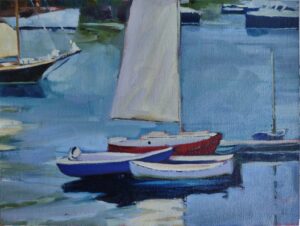

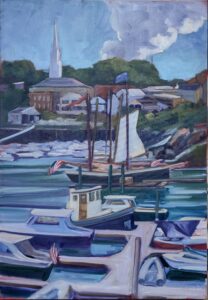

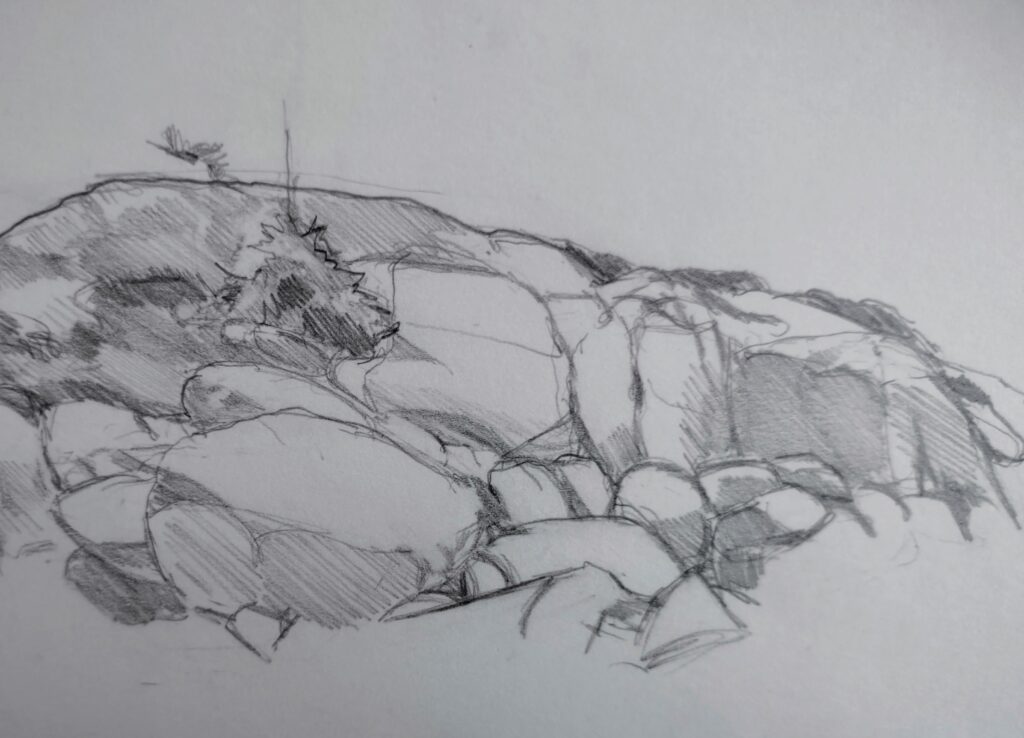

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.