Last year Jane Chapin sent me a video of a ranch hand chasing a grizzly. “Get out of here, bear!” he kept shouting, moving fast along with his blue-heeler behind the scurrying bear. I assumed the man was on horseback, but today he told me he’d been on foot. He was doctoring an injured calf when the bear showed up. That took guts, but what else could he do?

This young man has the dapper mustache of a 19th century derring-do on a surprisingly young face. “Are the bears hibernating now?” I asked him.

“They never truly hibernate,” he told me. I guess that’s a myth they tell easterners to keep us visiting Yellowstone National Park in winter.

Monday night, he told me, a grizzly was nosing around the garage where two mule deer are dressed and hanging (he’s also gotten an elk this year). How did he know? “Grizzlies smell like really strong wet dog.”

Are brown bears and grizzly bears the same?

I always thought so, but apparently grizzlies are a subspecies of brown bears, which exist in temperate regions worldwide. But North American brown bear means grizzly.

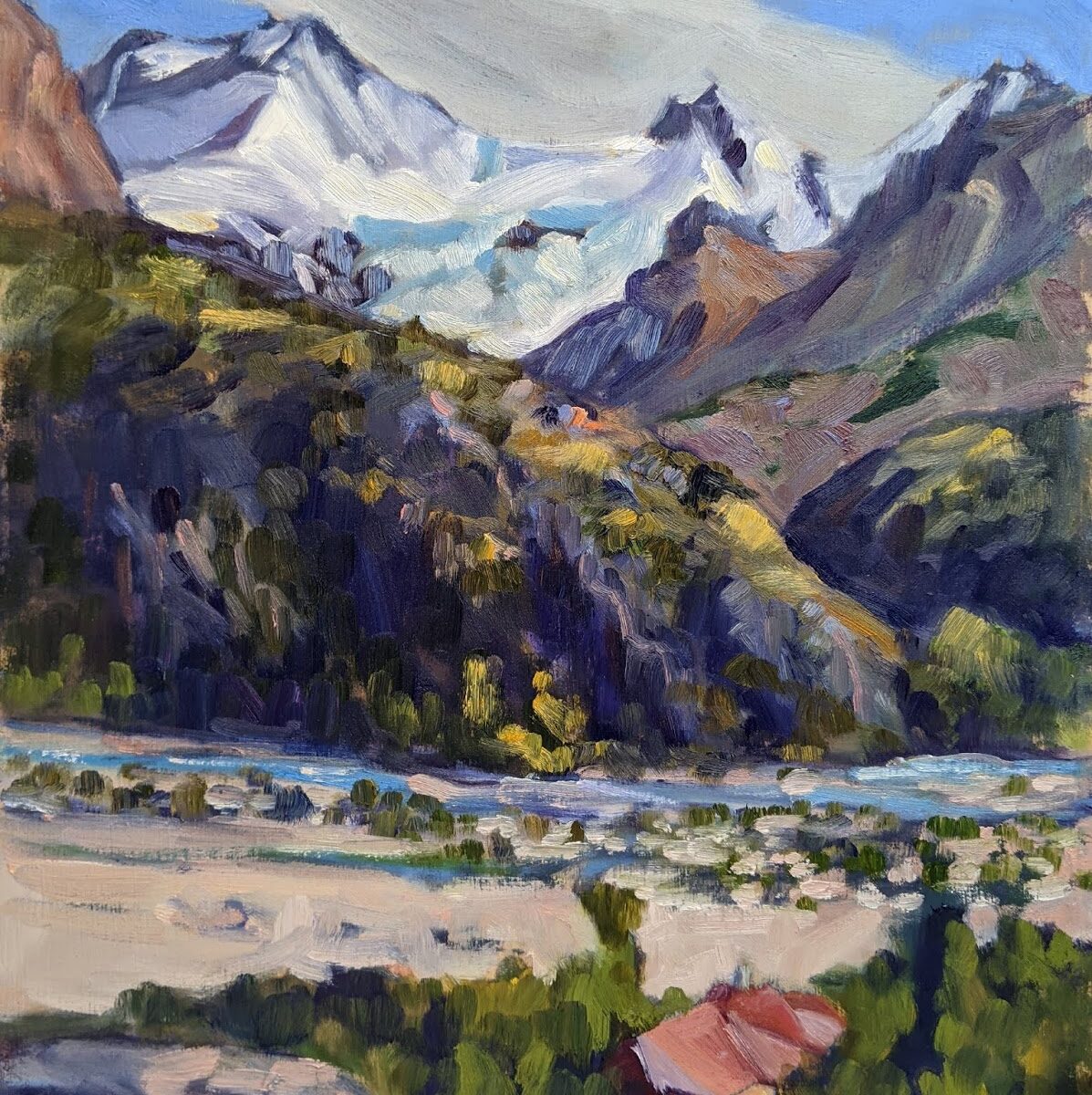

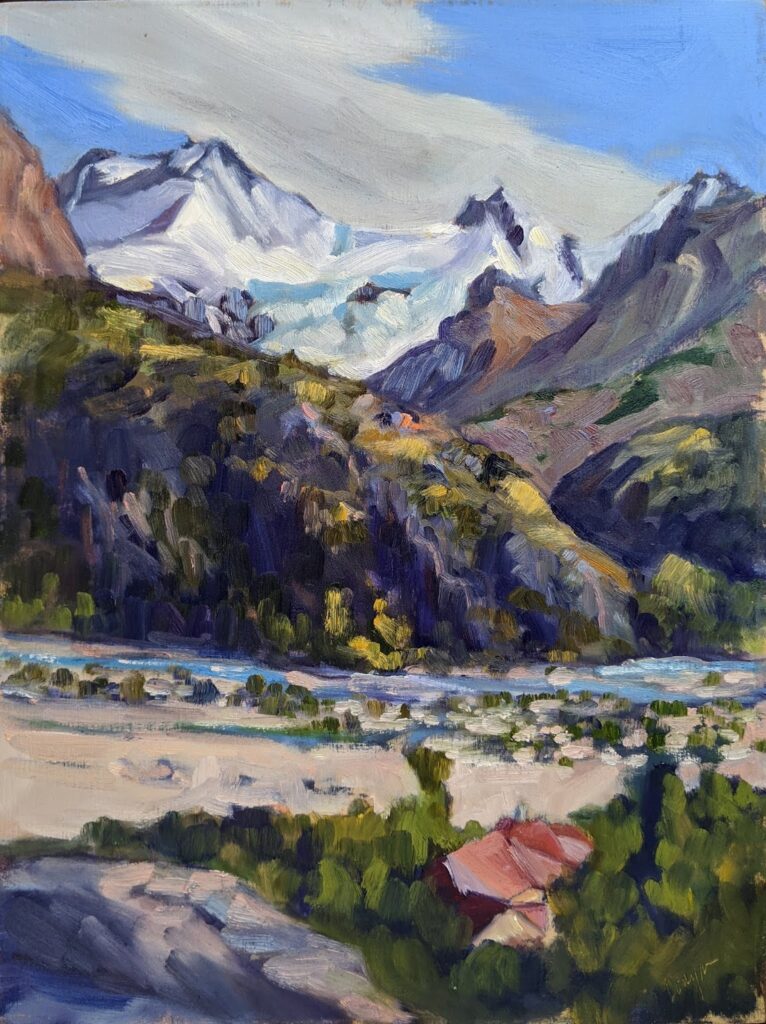

I’m along the south fork of the Shoshone River for a few days before I head east again. Yesterday’s storm was the first snow I’ve encountered this season. It was a wild temperature swing from the heat of Sedona last weekend.

The temperature here at the ranch is always lower than it is in Cody proper. Last winter when I was here the temperatures dipped below -30° F. That week, I saw wolves loping across the meadow; this week, a coyote sped across the road in front of me. Down by the river yesterday, I surprised a golden eagle.

We took a slow, slippery drive up the South Fork of the Shoshone River looking for bighorn sheep. They’re always elusive, but it’s elk season and hunters have perhaps pushed them farther up the slopes. A string of mules waited patiently near the river.

As dusk began to fall and the snow continued to blow, three of Jane’s horses made a rather silly break toward the ranch road. The youngest, Roscoe, reminds me powerfully of my last horse, who could be sly. As Roscoe thundered up behind Jane, my heart was in my throat. At the last moment, she swung under the split rail fence.

Sadly, I only saw Jane’s donkey (who is a middle-aged gentleman) from a distance. He’s hanging out by the river with new pals. “Jimmy, Jimmy Stewart!” I called vainly into the wind.

Yes, I am tempted to paint with every twist in the road, and my kit is right here. However, my time here is fleeting, and new experiences and friendship are both precious. I can always paint tomorrow.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.