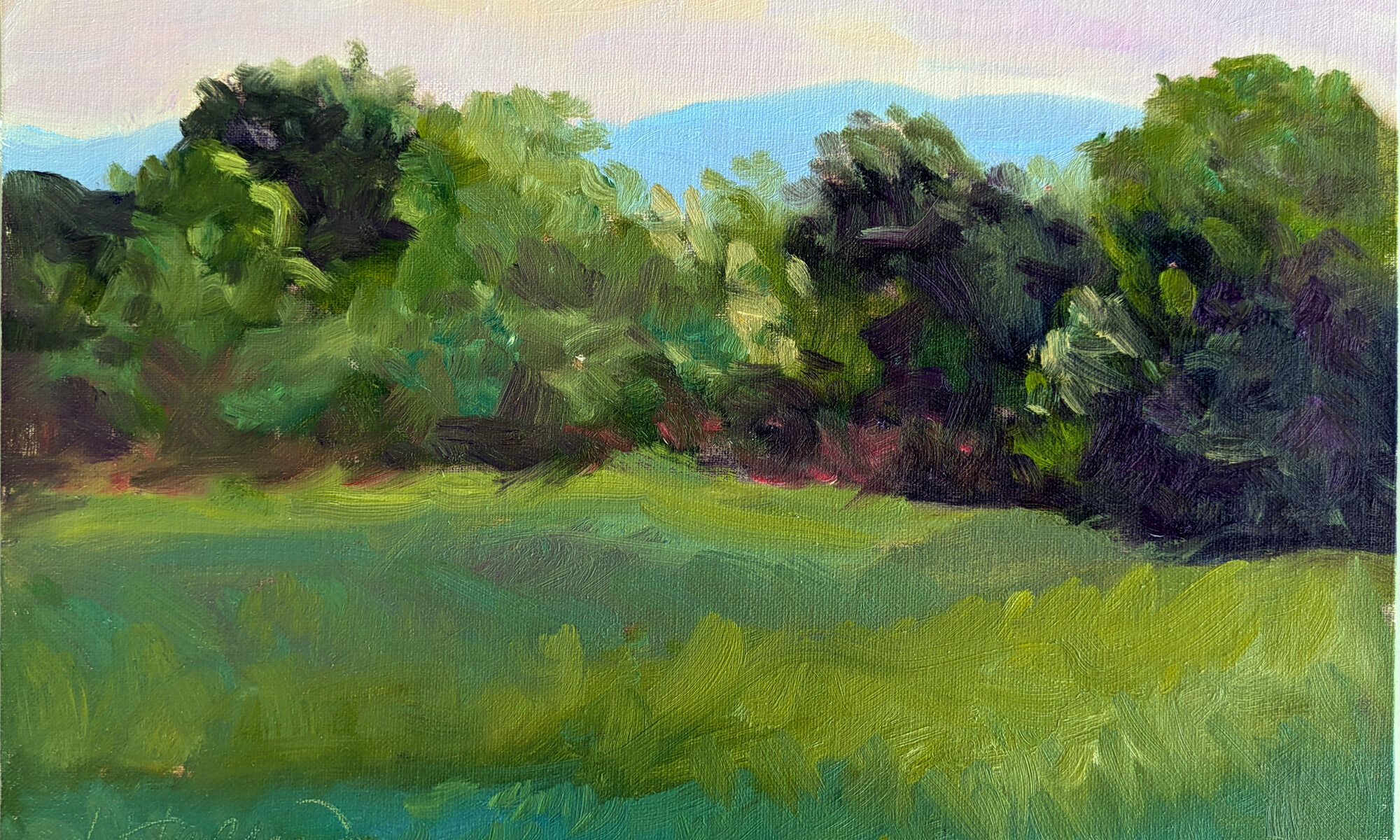

Last week I taught a delightful workshop in the Berkshires. I had demonstrated optical mixing (or broken color), and Lauren Hammond worked hard to execute the concept. Her finished painting was so lovely that I took a photo of it. She set it on the ground while she started something else. Thinking I knew better, I moved it to a nearby table so she didn’t inadvertently step on it. Our group was spread out over many acres, so most of the time, Lauren was alone at her easel.

“I think someone stole my painting!” she texted me. In decades of teaching, the closest I’ve ever come to that was when Sue Leo’s camera was lifted in Rochester’s Mount Hope Cemetery. But Mount Hope is near a sketchy neighborhood in a crime-ridden city. Lauren was in a place where I wouldn’t think twice about leaving my car unlocked.

“She’s just overlooking it,” I told myself, and I went back to help her find it. Other students helped us look and the venue manager contacted all her employees, all to no avail. It was gone. Lauren was the victim of an art heist.

I’m an inveterate reader of mysteries, so I hunted for clues. Aha, I thought, here’s one—a painting imprint on another nearby table. But that, sadly, was where the trail ended. I’m no Miss Marple.

People have posited various alternative theories to me. Perhaps it was mistaken for garbage and thrown away. Perhaps they thought it was left there for someone else to take (as in the Acts of Kindness movement). Perhaps it blew away. Because I saw the scene of the crime, I can tell you with absolute assurance that none of these things happened.

Art heist losses are hard to estimate but they’re estimated at around $4-6 billion US per year. Money laundering in the art market is an even bigger problem. In comparison, Lauren’s painting is a drop in a very big bucket. But I take it personally.

Let this be a lesson to you.

Even the safest painting sites need just one bad person to cause trouble, and there are many worse outcomes than losing a painting. Be in the zone but be aware of what’s going on around you. If you’re at all in doubt, paint in pairs. I’ve painted all over the world and never had a problem, but then again I’ve never had a student’s painting stolen either.

Why you shouldn’t steal paintings. Really.

If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you already know this, but humor me. Stealing art is rotten because:

- The artist put time, effort, and years of training into creating that work. It’s no different from any other tangible object with value;

- Stealing a painting deprives others of the opportunity to experience the work;

- Stealing is a crime that usually affects the little guys. We’ve abolished hanging as the punishment for theft, but I sure do understand why stealing riled up our ancestors;

- Paintings are personal, so stealing one is personal, too.

But I would never do that!

Photographers are people too, so the next time you’re tempted to use someone else’s online photo as reference for your painting, consider their property rights. Go outside and shoot your own reference picture. If that’s impossible, check Creative Commons for open-access images.

All’s well that ends well

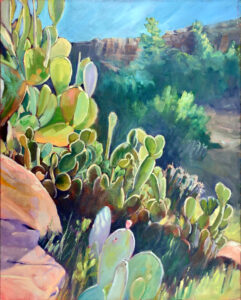

My goal on the last day was to encourage Lauren to paint something even stronger than the one that got away. I think she did so. It’s more complex and adventurous in design, but the color is just as well-executed.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.