“Why do odd numbers of objects in a composition look more ‘interesting’ than even numbers,” my correspondent asked.

“The explanation I’ve heard is that the brain wants to create symmetry, and when unable to do so because there are an odd number of objects, the gaze just continues to move around the composition. I briefly worked on a sheep farm, and ewes who had three lambs always seemed confused, like they were counting ‘one… two… wait a minute! Let me count again!’”

Carrie, even with twins I was confused most of the time. Sheep, like humans, have only two teats, but no opposable thumbs, and they’re kind of dumb. But back to your question:

“Is a desire for symmetry really hardwired into our brains? Or is this a cultural preference? Or a myth? If our brains want symmetry, then why not give it to them and make symmetrical art? Do people actually look at paintings of odd numbers of objects longer? Do they like them better?”

The short answer is that the brain seems hardwired to like complicated visual relationships.

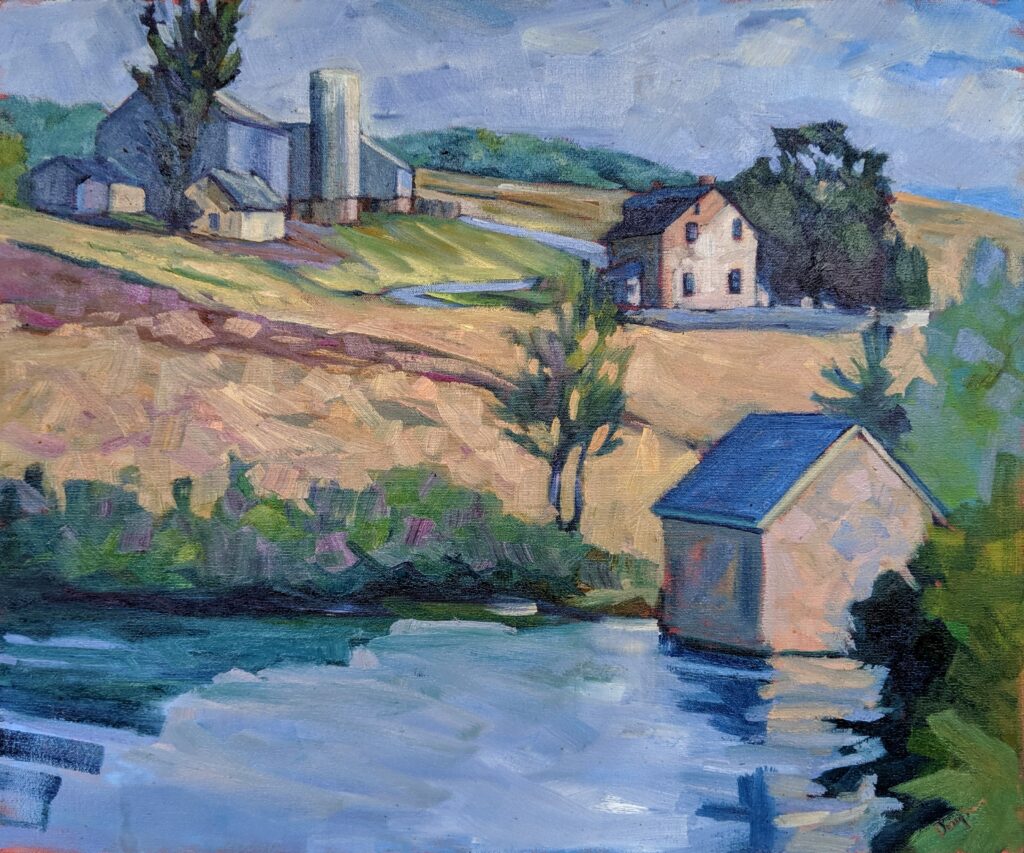

The Golden Rectangle, the granddaddy of all design ideas

That need for visual mystery is the basis for the Golden Rectangle. It resolves to 1.618:1, which is a ratio none of us can parse. Yet it looks pleasing. That’s because it derives from the Golden Spiral and the Fibonacci Sequence, with their perfect squares.

The Golden Rectangle is the first ‘absolute’ design model I ever learned. It has been used since at least the ancient Greeks. However, it doesn’t match up with the aspect ratio of modern canvases, frames and cameras, so we don’t hear about it as much anymore.

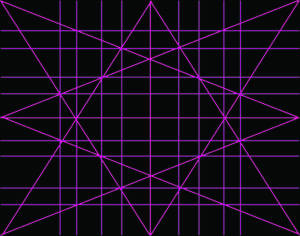

The rule of thirds

The rule of thirds never meant that you should have three objects. It divides an image into nine equal parts using two horizontal and two vertical lines. The most important elements of the image are placed along the lines or their intersections. That creates points of interest that are evenly spaced and aesthetically pleasing

It works, of course, but it is by no means the most interesting compositional grid. 1/3, although a repeating decimal, isn’t all that difficult for the brain to parse.

Is symmetry always bad?

Whenever someone tells me you should never put something smack dab in the middle of their canvas, I direct them to the Mask of Tutankhamun. It’s powerful, stately and grand. That’s why Renaissance artists like Leonardo da Vinci used symmetry to such good effect. It’s less popular today, perhaps because we don’t believe in absolutes truth much anymore.

Dynamic Symmetry

Jay Hambidge hoped to capitalize on the brain’s love of inscrutable proportion when he devised his theory of dynamic symmetry back in the 1920s. It’s since been discredited, but pops back up with dismaying regularity.

I learned it from the painter Steven Assael and fiddled with it for several years. In the end, what it taught me was not to put focal points at the edge of my canvas, which I’m telling you here, for free.

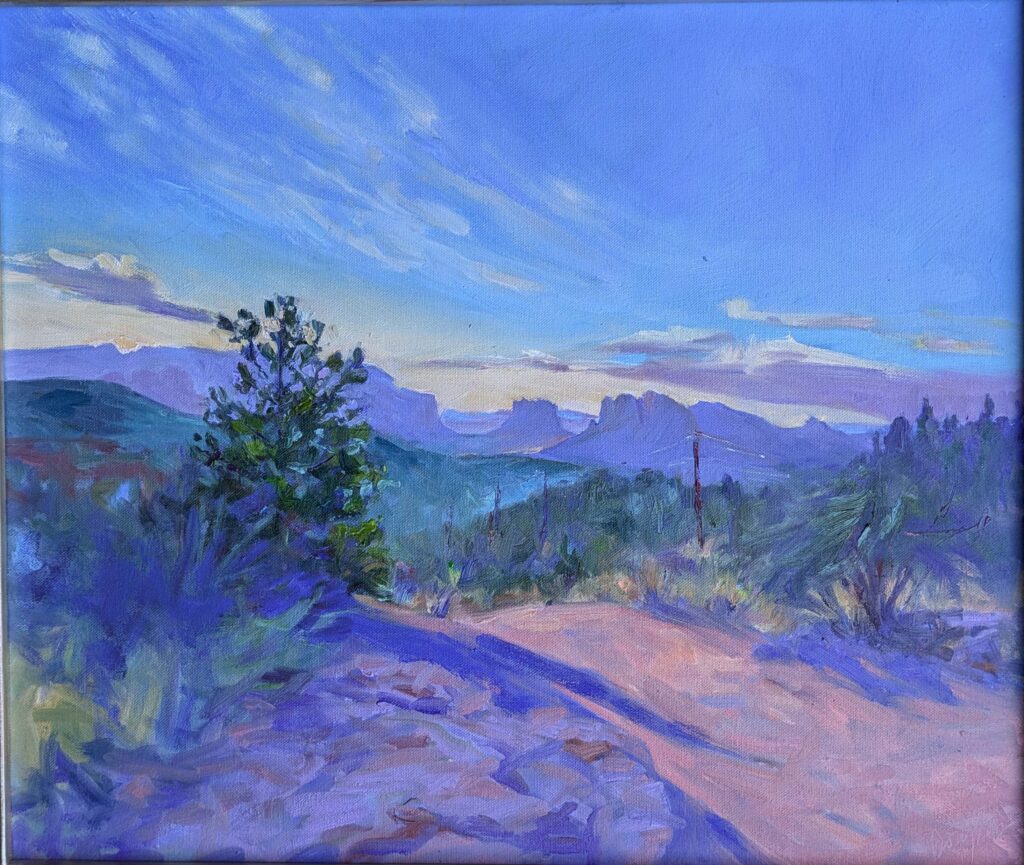

The circle

The circle is balanced in every direction. If symmetry were boring, a circle would be the last word in dullness. Instead, it’s fascinated us from da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man to now.

Besides being a model of human proportion, Vitruvian Man is a nod to an ancient math problem called squaring the circle. That was the challenge of constructing a square with the area of a given circle using geometry.

Ultimately it proved impossible. That’s because of our old high school buddy, π. π is what’s called a transcendental number, which just means it’s non-algebraic and goes on and on without ever repeating. Circles interest us precisely because they can’t be pushed into a square hole (and vice-versa).

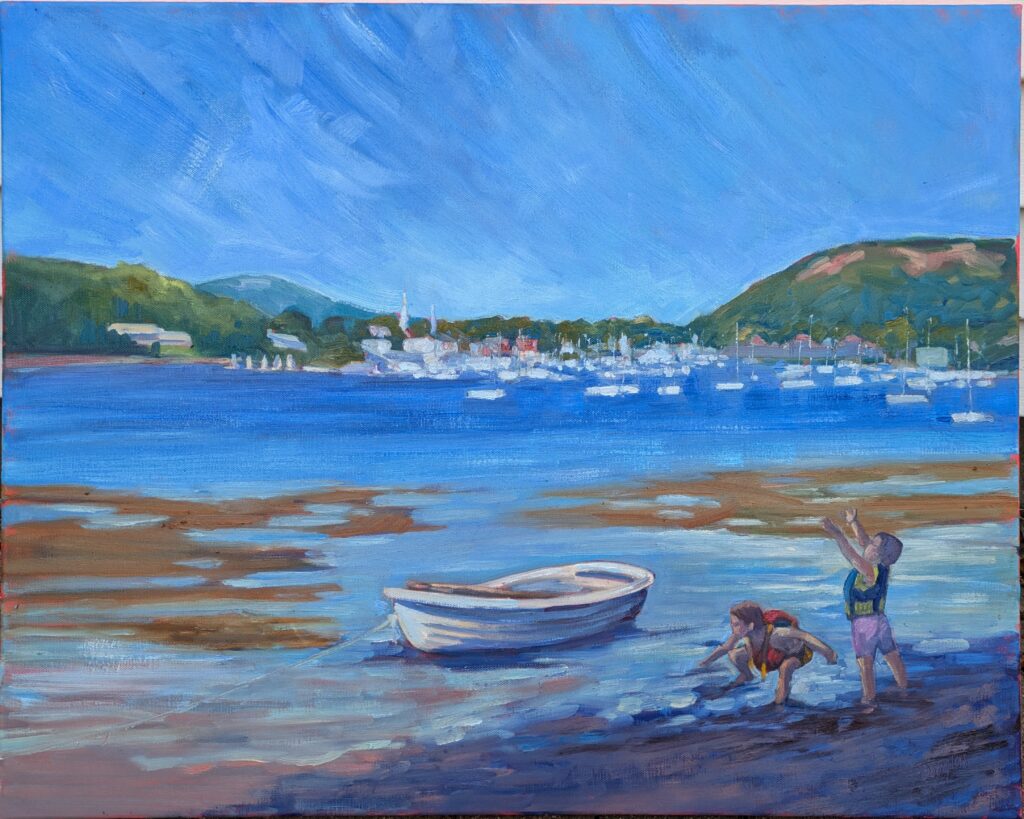

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.