As with abstract painting, abstract drawing is the opportunity to explore design without the pressure of realism. The ante is further reduced by dropping color. You need few materials:

- A sketchbook, drawing paper, or newsprint.

- Pencils, pens, markers or charcoal.

Start by loosening up

This can be difficult for those of us who’ve spent years learning figurative painting. Here are some simple exercises that might help:

- Free doodling: Pretend you’re in a boring meeting and let your hand move randomly across the page.

- Automatic drawing: This is a technique first developed by the Surrealists in an attempt to access the subconscious. Close your eyes and let your pencil move intuitively. Minimize or eliminate rational thought and conscious planning.

- Music for inspiration: Blast tunes and draw lines and shapes that match what you hear.

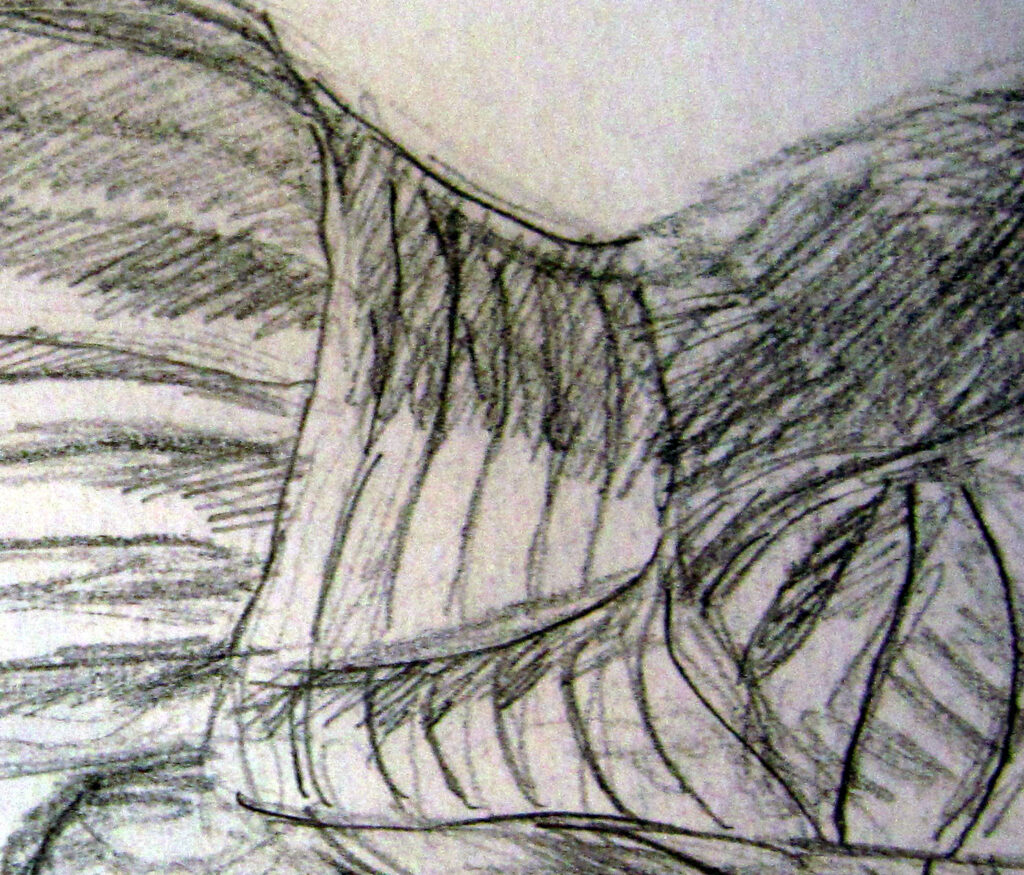

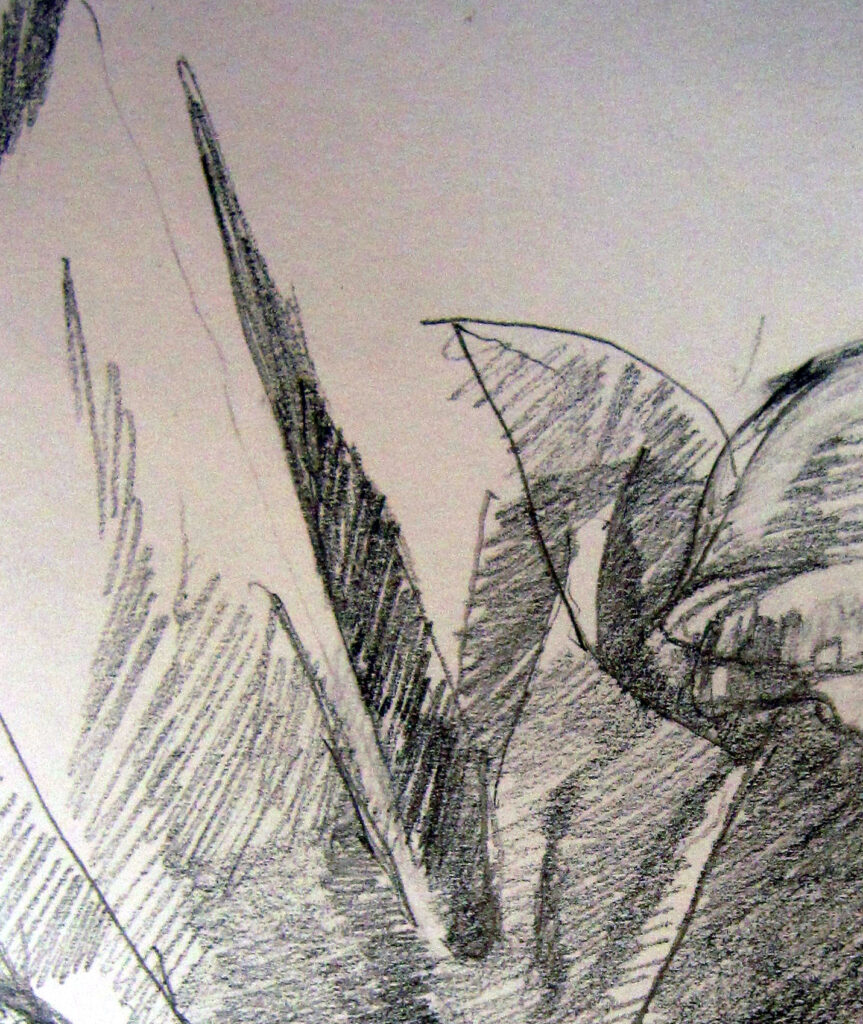

- Continuous line drawing: Without lifting your pen/pencil, create an abstract composition by moving your hand freely. Let the lines overlap and intersect naturally.

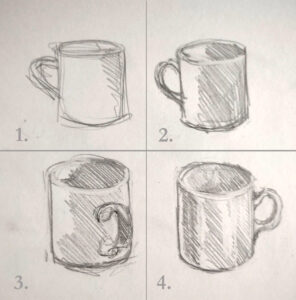

- Draw random geometric or organic shapes across the page. Experiment with filling some shapes with patterns and shading.

- Make a messy scribble on the page. Then refine and build on the scribble.

- Draw an emotion or word: Pick any emotion, and express it through lines, shapes, and value.

- Smear, baby, smear: Make a big blotch of charcoal on newsprint, and then lift and smudge it with a kneaded eraser. Enhance as you see fit.

- Repetition: Repeat a shape in different sizes and orientations, allowing patterns to emerge naturally.

Once you’ve gotten used to ignoring reality…

… you can start experimenting with lines and shapes. Focus on curves and geometric forms. Play with thickness, repetition, and patterns. Explore different techniques, including layered marks, contrasting densities, and the bold use of negative space.

A common exercise when I was in school was to draw with your non-dominant hand. It reduces control, but I doubt it gets you in touch with your emotions. Closing your eyes might be more helpful. Keep playing; keep experimenting. You’re unlikely to find a breakthrough on the first try.

Why do I want to try abstract drawing?

Learning to draw non-figuratively frees you to start combining figurative and non-figurative elements in striking new ways. Even if you never want to abandon realism, it will make you a better designer.

Inspiration for abstract drawing

Abstract art was the primary artistic movement of the 20th century. Its practitioners are too numerous to mention. I’m partial to the works of Robert Delaunay, Charles Demuth and Clyfford Still, myself. Find a few you love and study their work.

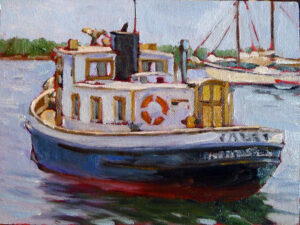

Perhaps more importantly, observe textures and patterns in nature. The symmetry, spirals, branching, waves, cracks, tessellations and fractals of nature are deeply programmed in our brains. The line between figurative and non-figurative art is often tissue-thin.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.