“Use it up, wear it out, make it do or do without,” is a famous Yankee proverb. I love to sew but don’t much like mending. It hardly seems worth the effort, especially to replace the zipper in an already worn pair of trousers. If I was in any doubt about the infrequency of my sewing, my needle had spots of corrosion.

I was once a fairly adept seamstress. Imagine my annoyance, then, when I sewed the blasted zipper in wrong and had to rip it out. (It still looks awful, but that’s my husband’s problem. At these prices, he’s got nothing to complain about.)

There are some skills, like breathing, that you don’t forget. There are many others that get rusty if they’re not used. Use them or lose them.

What’s stopping you?

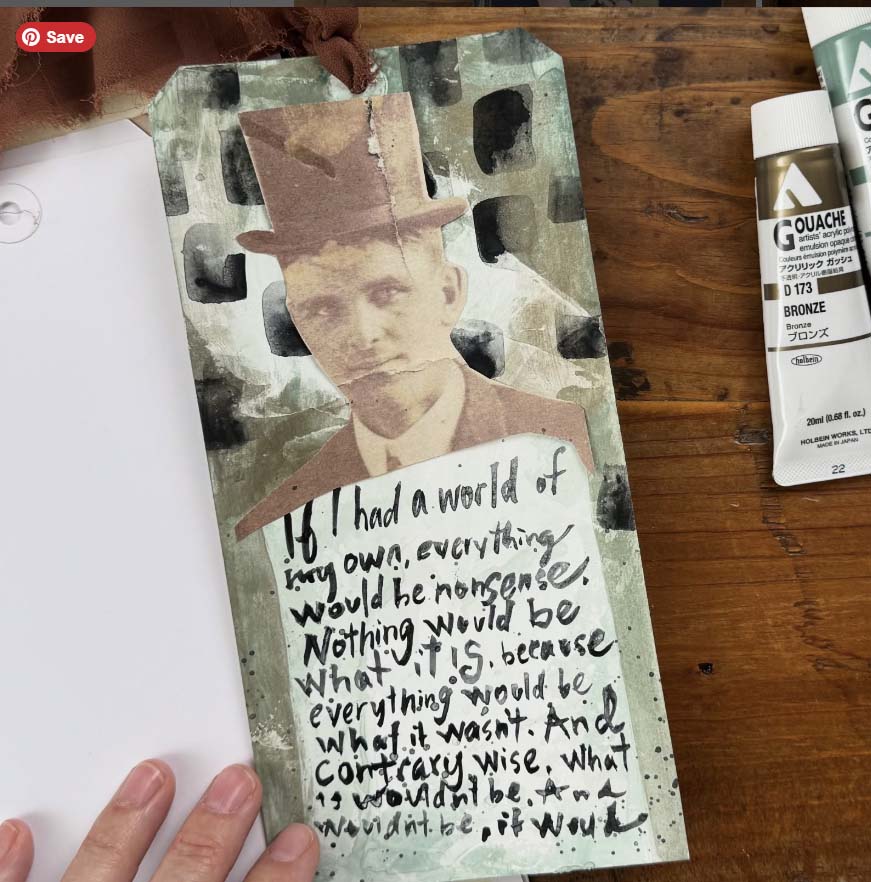

There are many reasons people don’t do creative work. The biggest of these is fear of failure. Starting something unknown means seeing all our flaws and shortcomings magnified. We worry that our work won’t be good enough. It’s easier to imagine what you might do than to take the risk of doing it.

Perfectionism is artistic expression’s greatest enemy. There are people who feel that if they can’t create something perfect, it’s not worth trying at all. But nobody has ever created perfect art; nor will they.

Perhaps you were told that you were a linear thinker rather than a creative one. That’s an absurdity; creativity, like any other form of thinking, takes practice. Or you were told that art is an innate talent. It isn’t, any more than understanding science or engineering is innate. They all take work.

“When I was young, I shied away from art because I mistakenly thought that either you had talent/ability or you didn’t. Period. It didn’t occur to me that like music or writing, you can take a bit of raw talent and get better at it with lessons and practice,” my student Sandy Sibley said.

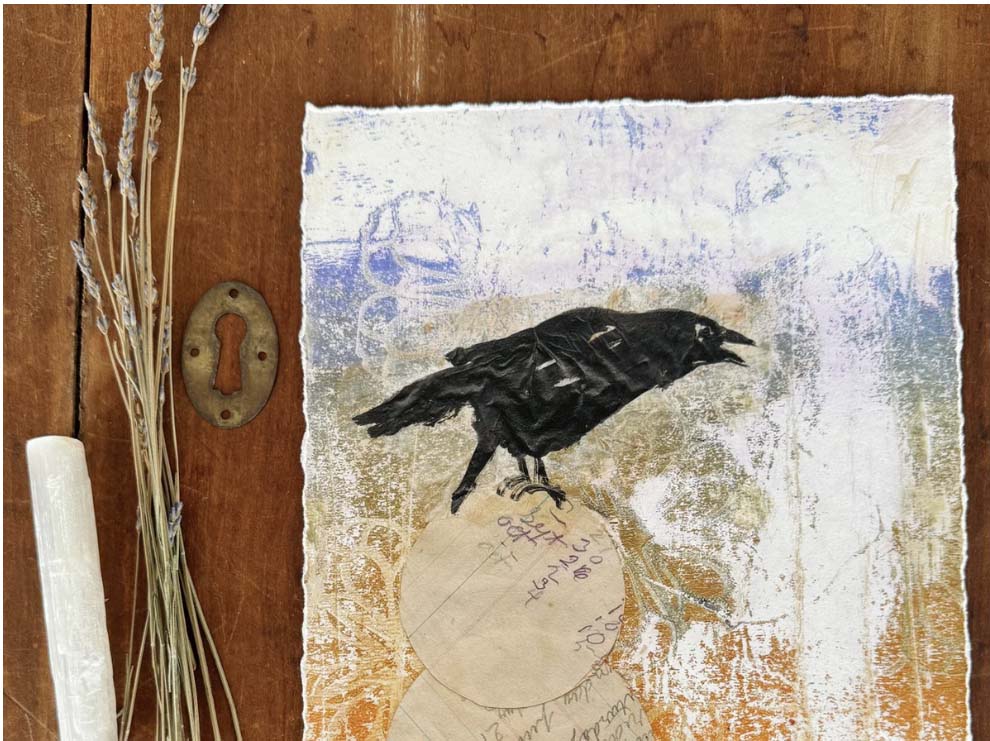

If you’re someone who’s been discouraged from the creative arts, you may lack self-confidence. Social media doesn’t help. Just as we’re all set up to compare our looks to those of influencers, we’re all ambushed by the highly-polished works we see on the internet. (They may, in fact, be totally lacking in charm in the real world, but that’s a different issue.)

Lastly, your routine might not allow for creativity. I don’t sew now because I haven’t got the mental or physical space, so I understand if you can’t find a place to paint. But there’s always room to draw. It requires a sketchbook and a pencil.

Do you feel like you challenge your own creativity?

Yesterday I saw pussy willows along the trail. A new season means new opportunities, and I encourage you to find a way to express yourself this spring, through gardening, cooking, woodworking, sewing, painting, sculpting—in short, anything that brings you the joy of creating.

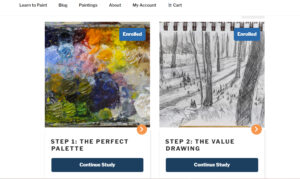

I’m offering two new classes this spring

Zoom Class: Advance your painting skills

Mondays, 6 PM – 9 PM EST

April 28 to June 9

Advance your skills in oils, watercolor, gouache, acrylics and pastels with guided exercises in design, composition and execution.

This Zoom class not only has tailored instruction, it provides a supportive community where students share work and get positive feedback in an encouraging and collaborative space. Learn More

Tuesdays, 6 PM – 9 PM EST

April 29-June 10

This is a combination painting/critique class where students will take deep dives into finding their unique voices as artists, in an encouraging and collaborative space. The goal is to develop a nucleus of work as a springboard for further development.

We will examine work against both the formal standards of design and the artists’ stated goals. Learn More