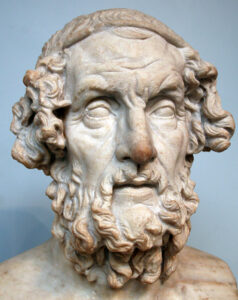

In his fabulous book Bright Earth: Art and the Invention of Color, Philip Ball muses on what Homer meant by ‘the wine dark sea.’ Homer liked this epithet a lot; he used it five times in the Iliad and twelve times in the Odyssey. The only other time Homer used that word for wine, it was to describe reddish oxen.

A sea can suddenly turn red for brief periods with algae bloom, or a glass of wine can turn blueish if the pH is raised, but Homer was using the term to describe stormy weather: what we might describe as an ominous, slate-blue sea.

This paradox of archaic Greek has baffled linguists for a long time. British statesman William Gladstone published an exhaustive study in 1858, where he was the first to note that the Greeks didn’t use the word ‘blue’ in the same way as modern writers. The word kyanós (which comes down in English as ‘cyan’) in later Greek meant blue. But for Homer, it almost certainly meant dark, since he used it to describe the eyebrows of Zeus.

Greece is full of sapphire seas and clear blue skies. It’s odd that they didn’t have words to describe a range of blues, let alone one.

Gladstone proposed that archaic Greek focused on value, not on hue. (For a primer on the meaning of these terms, see here.) Gladstone was immediately misunderstood to be saying that ancient Greeks couldn’t see color. That’s something he never wrote or believed.

The Torah (approximately the same age as Homer’s epics, and much better preserved) is a little better on color. It mentions black, white, crimson, blue and purple. However, most of its color references are by way of precious stones or metals.

Which came first, language or perception?

Many social scientists have debated whether color recognition is an innate human trait or whether it’s culturally-derived. Some believe the language a person speaks affects the way he or she thinks. But if you accept that, does language determine perception or perception determine language? (I’m not sure how you get a paying gig thinking about this stuff, but it’s sure interesting.)

More basic is the question of whether human biology is the same for all of us, a discussion that has led to some pernicious racist beliefs over the centuries. If we’re all made the same, we should see (and talk) about color the same. Practically speaking, we don’t; even in the modern world, there are differences in how cultures describe color.

Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote, “The limits of my language means the limits of my world.” If so, how does that affect our perception of color?

The word ‘blue’ is missing from many ancient languages. There is no distinct word for the color in ancient Chinese (where blue and green were interchangeable) or Sanskrit. Egyptians, however, did have a distinct word for blue. Not surprisingly, they also developed the first blue dye, which was related to their early production of glass beads.

Other colors such as black, red, white, and yellow are all mentioned by Homer. Perhaps not coincidentally, black, red and yellow are the primary colors of archaic Greek pottery. Perhaps color terms were based on material culture and not on nature.

In English, we’re told, we have 11 basic color terms: black, white, red, green, yellow, blue, brown, orange, pink, purple, and grey. That’s absurd. We have pink; to a scientist, that might just be a light form of red, but everyone else understands exactly what it means. We have coral, mauve, periwinkle, chartreuse, indigo, and countless other color terms. Homer used about 9,000 words total in his two epics; modern English has more than 170,000. It doesn’t mean we experience that much more color; we just have a lot more language to describe our perception.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.