When the wind pummels my studio incessantly (as it’s done for the last week) Willa Cather’s lines come to mind: “…the wind sprang up afresh, with a kind of bitter song, as if it said: ‘This is reality, whether you like it or not. All those frivolities of summer, the light and shadow, the living mask of green that trembled over everything, they were lies, and this is what was underneath…’” Cheerful woman, that.

Unlike Cather, I’m not obsessed with death; still, it’s sometimes worth thinking about. “When a person dies, a whole world is destroyed,” is something my Jewish friends say. It’s a variation on a Talmudic teaching: “Whoever destroys a single soul, destroys an entire world; whoever saves a single soul, saves an entire world.”

I was thinking about this as I reluctantly closed the last novel in a series by the late Canadian-American writer Charlotte MacLeod. Miss MacLeod suffered from Alzheimer’s disease, that terrible thief of minds. When she put down her pen in 1998 or thereabouts, several whole crazy worlds stopped.

Dorothy L. Sayers was more serious than MacLeod. She died while translating Dante’s Divine Comedy into English, but most of us know her creation Lord Peter Wimsey. That doesn’t make her scholarship unimportant; the hell that most of us visualize is for the most part Dante’s artistic legacy.

What will be my artistic legacy?

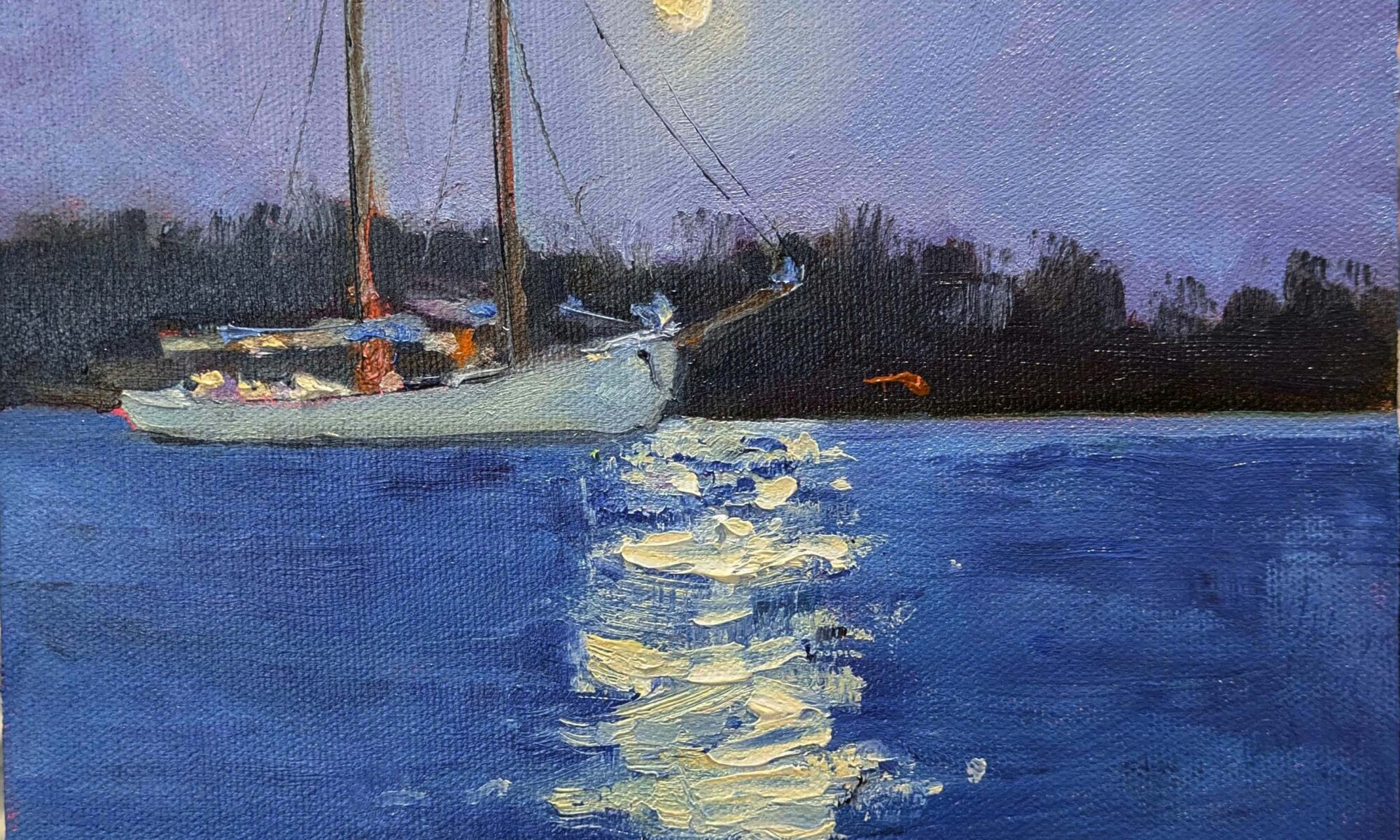

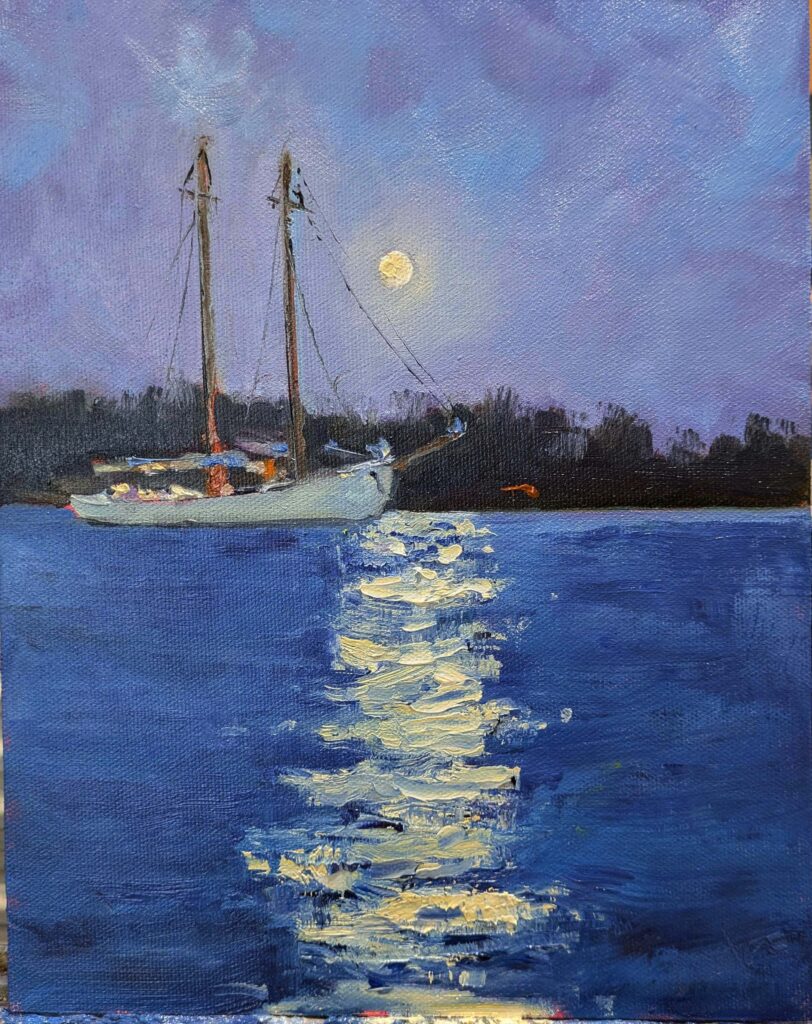

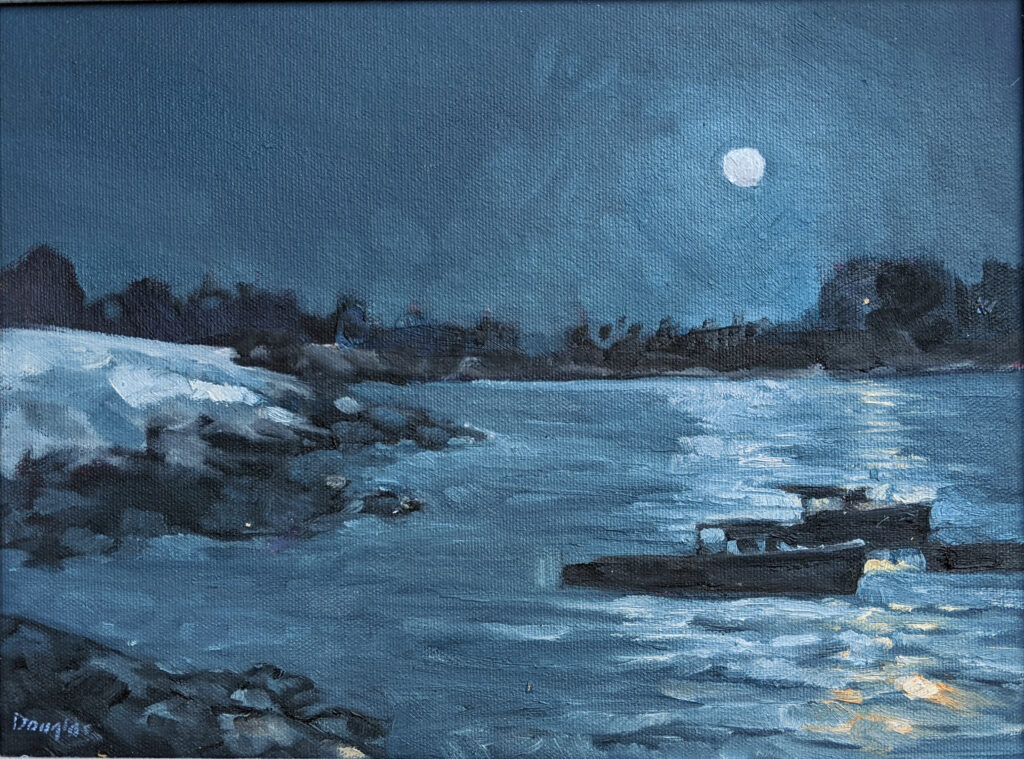

When I die, my paintings will be part of my estate, inherited either by my husband or children. They might keep them, sell them, donate them, or burn them in the backyard. I’ve painted and sold enough work that it’s out there in the world regardless of what they do. I can’t predict whether the remainder will increase in value or make good firewood.

The biggest factor in the future value of your art is what you yourself have done to market it, but that’s by no means the only story. Vincent van Gogh might have lapsed into obscurity after his death had it not been for his brother’s widow, who recognized a marketable asset when she saw one. She needed to sell his paintings and, in the process, created his artistic legacy.

The primary value of your art after you die isn’t monetary (what the heck, you won’t be able to spend it) but in its future influence. Dead painters bring me joy every single day. If we can pay that forward, painting will be well worth the time and care we’ve lavished on it.

Nothing lasts forever

This week the Getty Villa was threatened by the Palisades fire. That’s the part of the Getty that contains Greek and Roman art, already in limited supply in this world. The collection survived in part because of its state-of-the-art design but also because its staff has been ruthless in clearing brush.

That area is home to many cultural landmarks as well as some of America’s most luxurious homes. It’s likely that a lot of art has gone up in smoke this week. While that’s small potatoes compared to the human cost, it’s a good reminder that nothing—including great art—lasts forever. The bottom line for each of us is our non-tangible legacy: our character, generosity, wisdom and kindness.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.