“How do you get into shows like Camden on Canvas?” a reader asked in response to Friday’s post. “It seems like I just keep getting rejected over and over.”

When I was young, I was very naive. I thought I could apply to prestigious shows and I’d automatically get in, because the jurors – of course! – would instantly recognize my genius. It didn’t help that I had some early successes, which were the equivalent of a new golfer hitting a hole-in-one. They didn’t signify anything about my skill, but they made the inevitable rejection that much harder.

Today I’m no smarter, but I’m far more experienced. I’ve learned the hard way that the competition is fierce. We work our way up to big shows by putting in time and effort at smaller shows. Jurying is subjective, so you might win an award one year, and be rejected another year. (I’ve never had much luck trying to game the system by only applying to shows where I think the jurors will like my work.) Moreover, there are some factors you can’t know, such a gallery’s pressing need to have more of one medium, or artists of a particular demographic, in a show. You can’t take any of it personally.

It’s partly a game of numbers; the more events you apply to, the more you’ll get into. I’m a better painter than I was 25 years ago. I hope to be even better 25 years hence. My success rate is better than it was a quarter-century ago and I expect it will continue to improve.

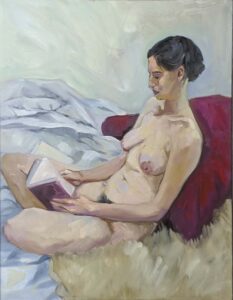

Painting in front of an audience

“I hate painting in front of crowds,” a friend kvetched as we scouted locations. In the case of nerves, as I wrote last week, desensitization helps. But for most experienced painters, the problem isn’t nervousness but distraction.

That’s a harder nut to crack. We are supposed to talk to passers-by, engage them in the painting process, and encourage them to attend the auction or sale. However much that helps business, it can have a toxic impact on your work.

Sometimes I do two paintings: one is a serious entry for the auction, and one is theater. But that’s not always possible.

I cope with frequent interruptions by digging deeper into my process. That way, when I’ve lost the thread, I can go back over my mental checklist. And when I’ve gone completely off the rails, I take a break and go bother some other artist.

There are artists who simply can’t deal with the endless chatter. There are solitary perches even in Camden, where they’ll squirrel themselves away to paint. The downside is that they haven’t established a relationship with their audience, and that’s not good for sales.

What about the weather?

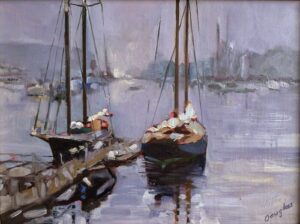

This has been a very unusual year. Fog is a beautiful part of our climate, but even lifelong Mainers have told me they’ve never seen this much dense fog.

Obviously, I’m not a meteorologist but since we’ve been in a fog pattern for months now, it’s unlikely to change by Friday. What’s a poor artist to do? Shorten the pictorial distance, play up the atmospherics, and, above all, count my blessings. It could be snowing.

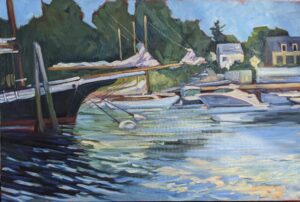

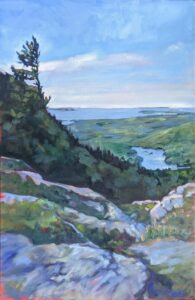

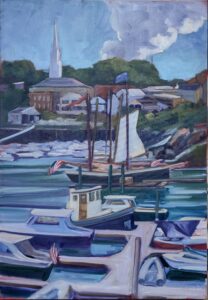

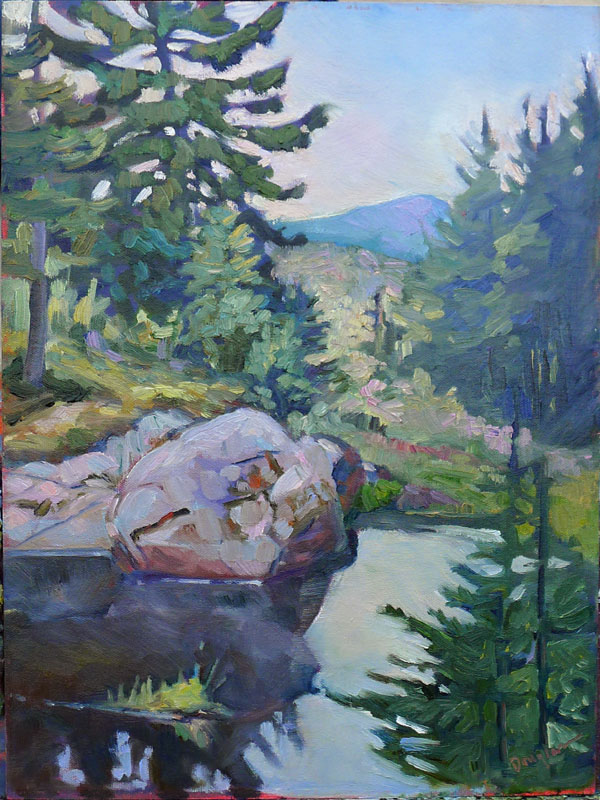

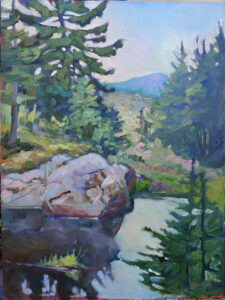

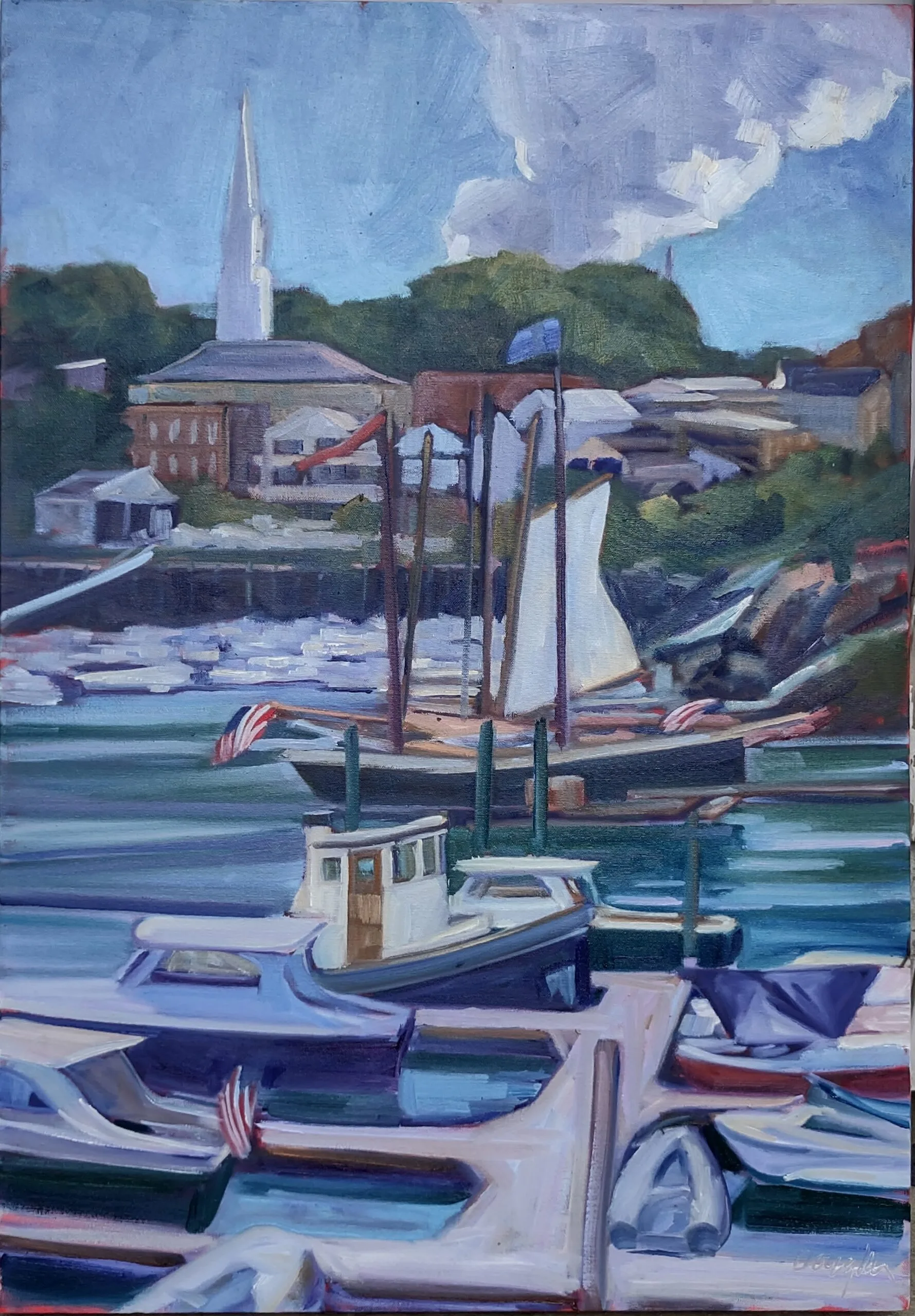

Camden on Canvas features “twenty-two notable New England landscape artists [who] will paint, en plein air, at multiple local sites” from this Friday morning to noon on Sunday. Start your tour at the information tent outside the Camden Library’s Atlantic Avenue entrance. There, you’ll find information about us and a map showing where we’re painting. The tent will be open from 9 to 5 Friday and Saturday, and 9 to noon on Sunday.

The reception and auction will be Sunday, July 23, 4 to 6 PM, and features Kaja Veilleux, who’s the most entertaining and professional art auctioneer I’ve ever worked with. Tickets are available here.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.