Last month I wrote that I was too idiosyncratic to be a forger. It requires sublimating your own creativity to another’s vision. What’s the fun in that? You might as well be an engineer; it pays better.

US copyright law says you can’t copy someone else’s work, except under limited circumstances. One of these is ‘transformative use,’ which has a bit of an “I’ll know it when I see it” definition.

Transformative use could mean:

- Parody: Creating a work that imitates or mocks the style or content of the original copyrighted material for humorous or satirical effect.

- Commentary or criticism: Using copyrighted material as a basis for commentary, critique, or analysis, where the new work adds new insights or perspectives.

- Educational or informational purposes: Incorporating copyrighted material into educational or informational content to illustrate a point or convey information.

- Remixes or mashups: Combining multiple copyrighted works to create a new, original work with a different meaning or expression.

That last one is where the visual artist has some latitude. For example, I might want to put an 18′ Grumman aluminum canoe in a painting and am too lazy to walk out to the back yard and photograph my own. If it’s a detail in an otherwise completely different work, I can reference someone else’s photograph. I cannot, however, copy Dorothea Lange’s dustbowl photographs verbatim and expect to get away with it. Of course, there’s a lot of grey area in between these two examples.

Transformative use is judged on a case-by-case basis, which is why famous artists like Jeff Koons keep stealing from less-well-known ones. They can better afford protracted legal cases.

British artist Damien Hirst also has a long rap sheet when it comes to plagiarism, but he may be the first artist in history to be accused of forging his own work.

Among several examples reported by the Guardian is an $8 million, 13-foot tiger shark split into three sections and suspended in formaldehyde at the Palm Hotel and Resort in Las Vegas. It was dated 1999, but was made in 2017.

The works were first shown at a 2017 Hirst solo show called Visual Candy and Natural History, and dated “from the early to mid-1990s.”

“Formaldehyde works are conceptual artworks and the date Damien Hirst assigns to them is the date of the conception of the work,” Hirst’s company said.

The artist’s lawyers added that “the dating of artworks, and particularly conceptual artworks, is not controlled by any industry standard. Artists are perfectly entitled to be (and often are) inconsistent in their dating of works.”

A more prosaic explanation is that Hirst’s reputation is in decline. More recent works do not sell at the prices he commanded when he was one of the fresh new Bad Boys of British Art. By backdating his catalog, he could hope to make more money.

Formaldehyde slows down but doesn’t stop decay. Some of Hirst’s earlier pieces are rotting, or the original specimens have been replaced. What a revolting job for the conservators, not to mention the gallery assistants who did the work in the first place. Formaldehyde is a highly toxic systemic poison that is a severe respiratory and skin irritant and can cause burns, dizziness or suffocation. If you’re inclined to deface artwork for political or environmental reasons, Hirst’s suspended animals seem a far better target than an irreplaceable oil painting.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

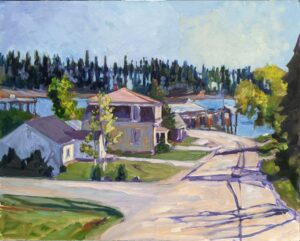

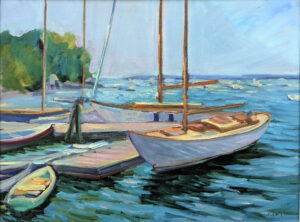

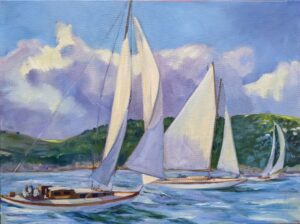

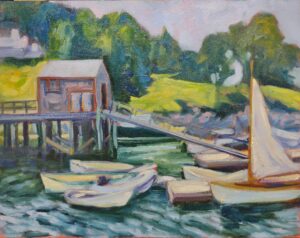

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

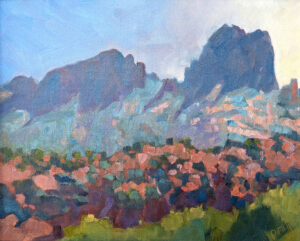

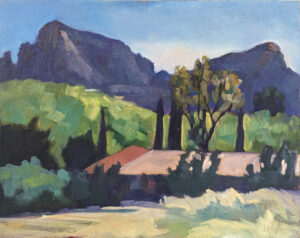

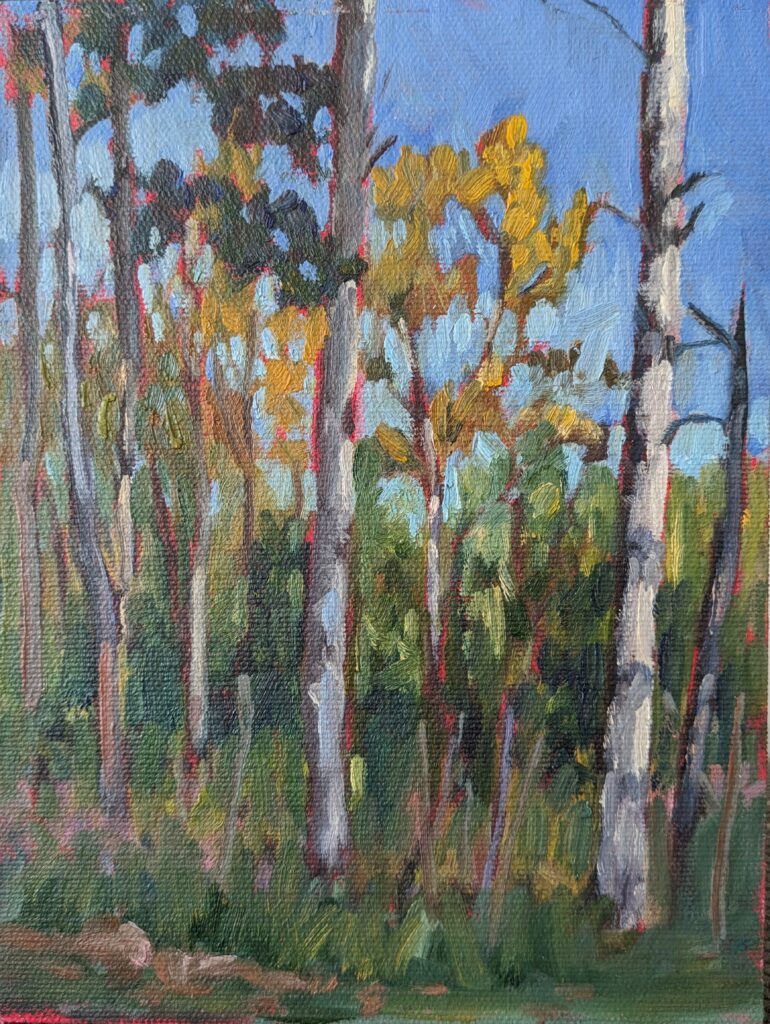

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.