A few weeks ago, Rachel Houlihan mentioned in one of my classes that she and another artist had run into me along the trail. “How many artists live near you?” another student marveled.

“Oh, lots,” she said. “Thousands. Many well-known ones,” and she proceeded list some of them. It’s true that you can’t throw a stick around here without hitting an artist (or attracting a dog).

I was reminded of this when walking nearby with Richard, a retired architect. “That’s the home of the actor Gabriel Byrne,” he said. (A few years ago, several people sent me this piece about him in the New York Times; I knew the locale intimately, but I still don’t know who Mr. Byrne is. His secret is safe with me.) It’s an arty place, and painting is only one aspect of it.

The best business decision I ever made

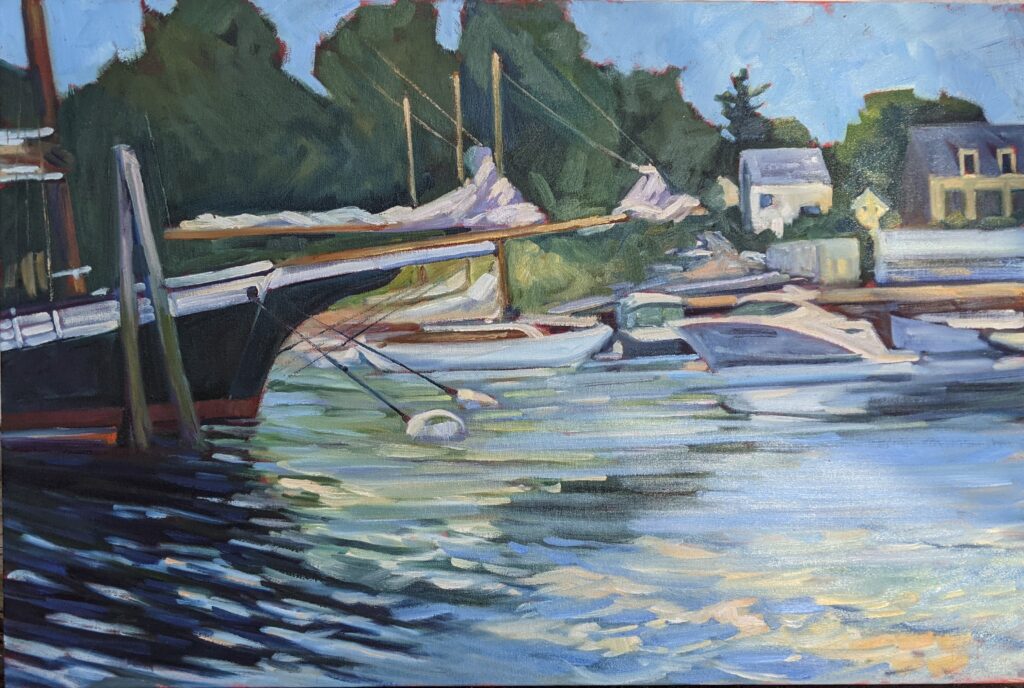

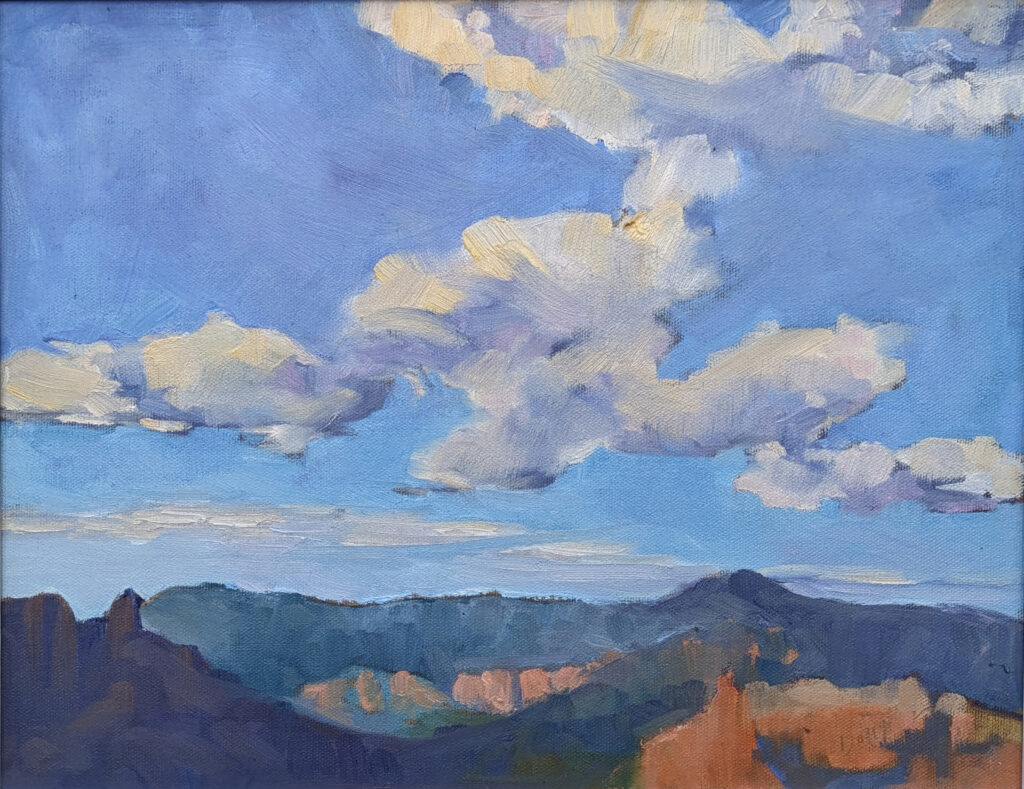

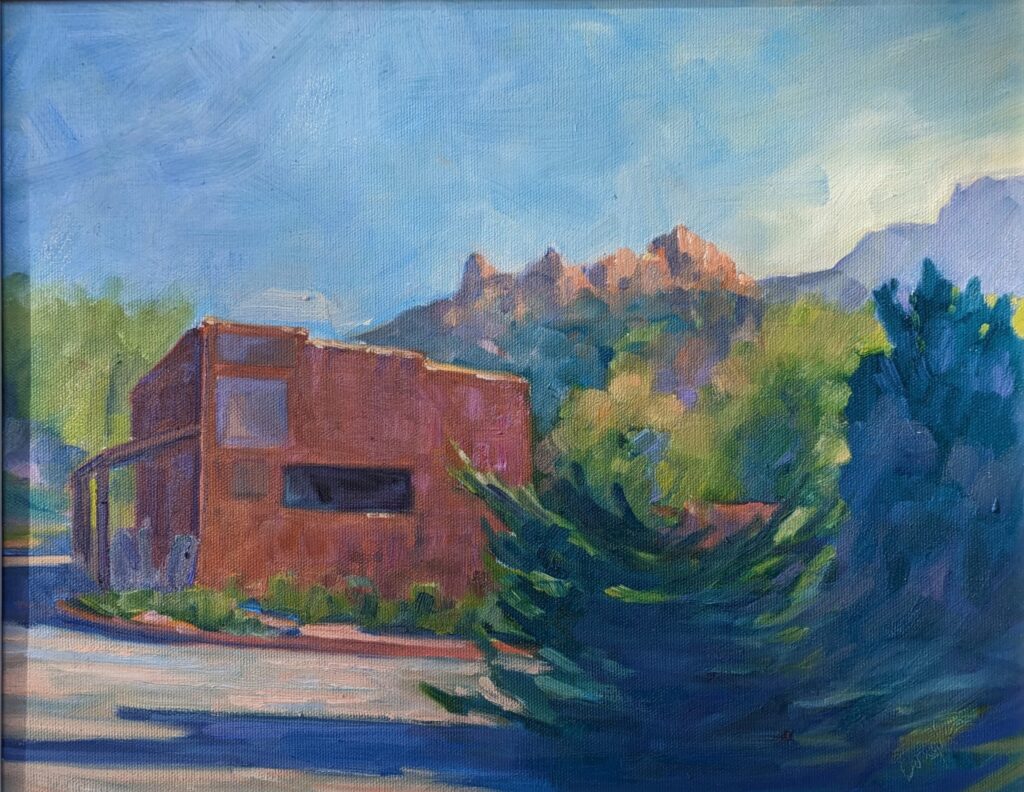

“What was the best business decision you ever made?” I was asked at the Sedona Entrepreneurial Artist Development Program. That was a no-brainer: it was to relocate to an artist community. In my case, that is coastal Maine, but in yours, it might be Santa Fe, NM; Sedona, AZ; Fredericksburg, Texas; Des Moines, IA; or another community I’ve never heard of.

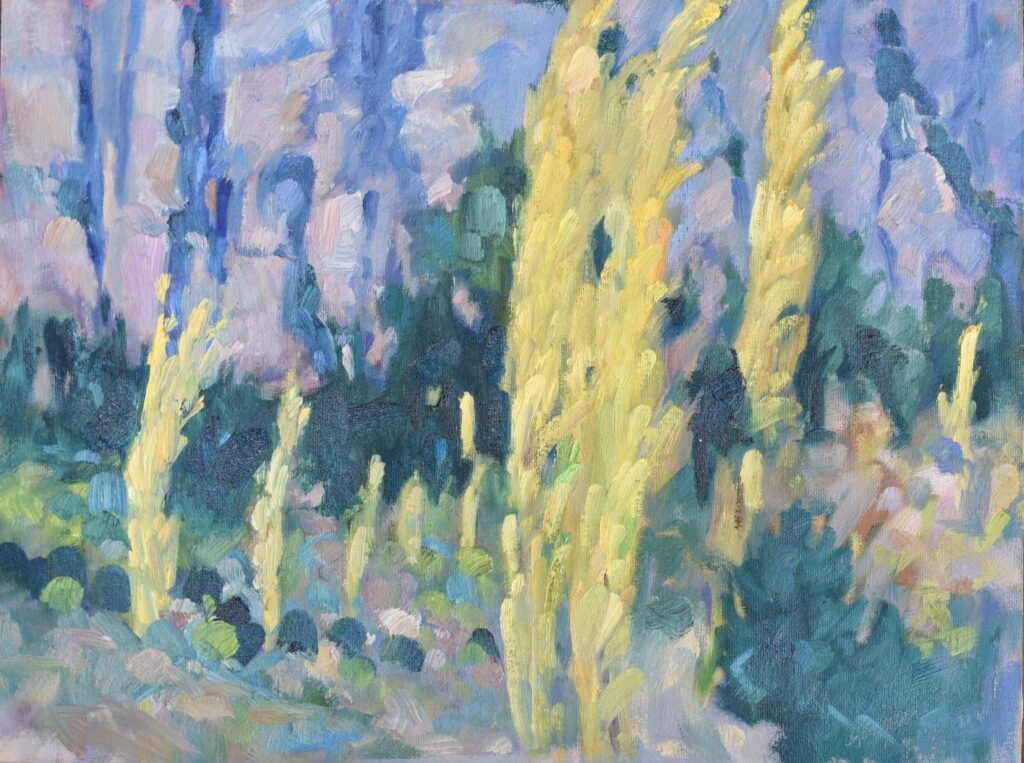

People are often drawn to an artist community—as I was—by the light, beauty, galleries, and the art scene, but there is always more to it. The more concentrated the art scene is, the more likely the work is to be directed towards a stylistic or thematic ideal. That’s how ‘schools’ of art develop. Iron sharpens iron, which means our own work gets stronger when we spark ideas off others.

Of course, you can seek community wherever you live, by working with the best artists you can find: at figure groups, plein air groups, ateliers and art associations. And five years of Zoom teaching has shown me how well the internet creates relationships between artists across the globe.

My mutual support system

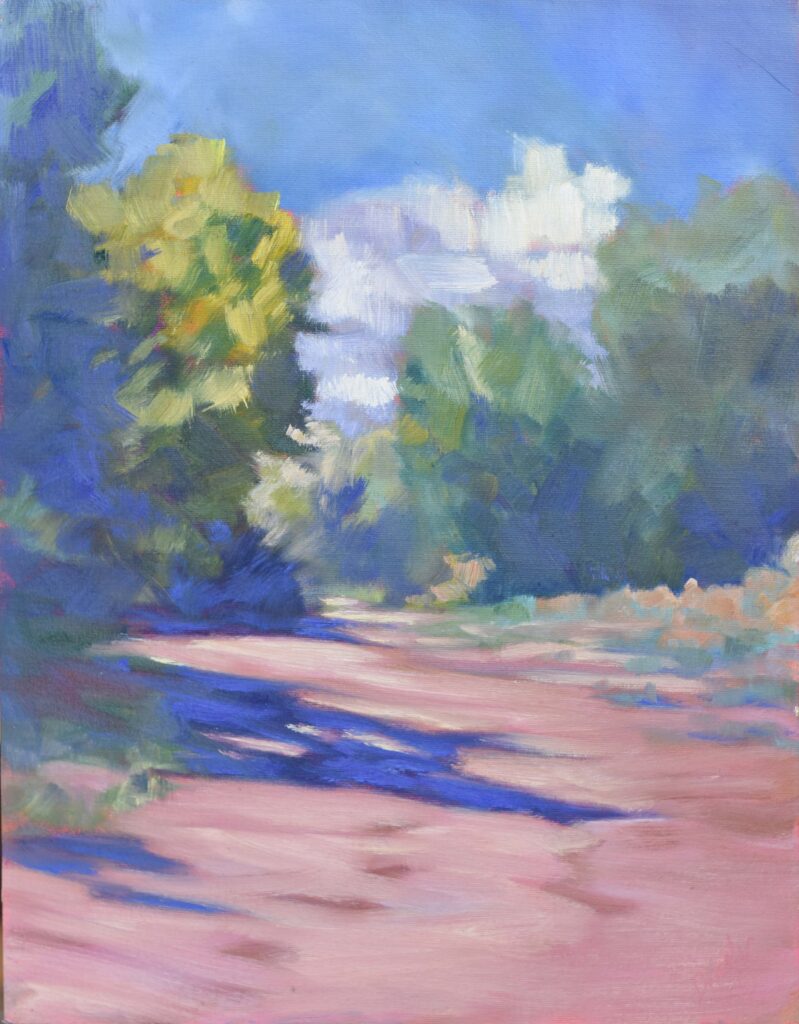

I have three peers I communicate with almost daily (and paint with as much as possible). They’re among the few people to whom I’ll complain about not getting into a show or about the disappointment of a selling price at an auction—or who will congratulate me when things go well.

I can also ask them for constructive feedback because I trust them. And I suppose if I really needed someone to walk my dog, they’d do that for me too; I’d certainly do it for them.

More importantly, there’s a sense of accountability with them. If I’m in a slump, they drag me out of it, and I try to do the same for them. And even in the snowiest of winter months, I don’t feel totally isolated.

Networking

I loathe the word networking, but the fact remains that living in an artist community means more opportunities to connect with art collectors, gallery owners, and industry professionals. It means more events, open studios, galleries and shows.

There also tend to be residencies, workshops, and mentorships in places where artists congregate.

This spring’s painting classes

Zoom Class: Advance your painting skills (whoops, the link was wrong in last week’s posts)

Mondays, 6 PM – 9 PM EST

April 28 to June 9

Advance your skills in oils, watercolor, gouache, acrylics and pastels with guided exercises in design, composition and execution.

This Zoom class not only has tailored instruction, it provides a supportive community where students share work and get positive feedback in an encouraging and collaborative space.

Tuesdays, 6 PM – 9 PM EST

April 29-June 10

This is a combination painting/critique class where students will take deep dives into finding their unique voices as artists, in an encouraging and collaborative space. The goal is to develop a nucleus of work as a springboard for further development.

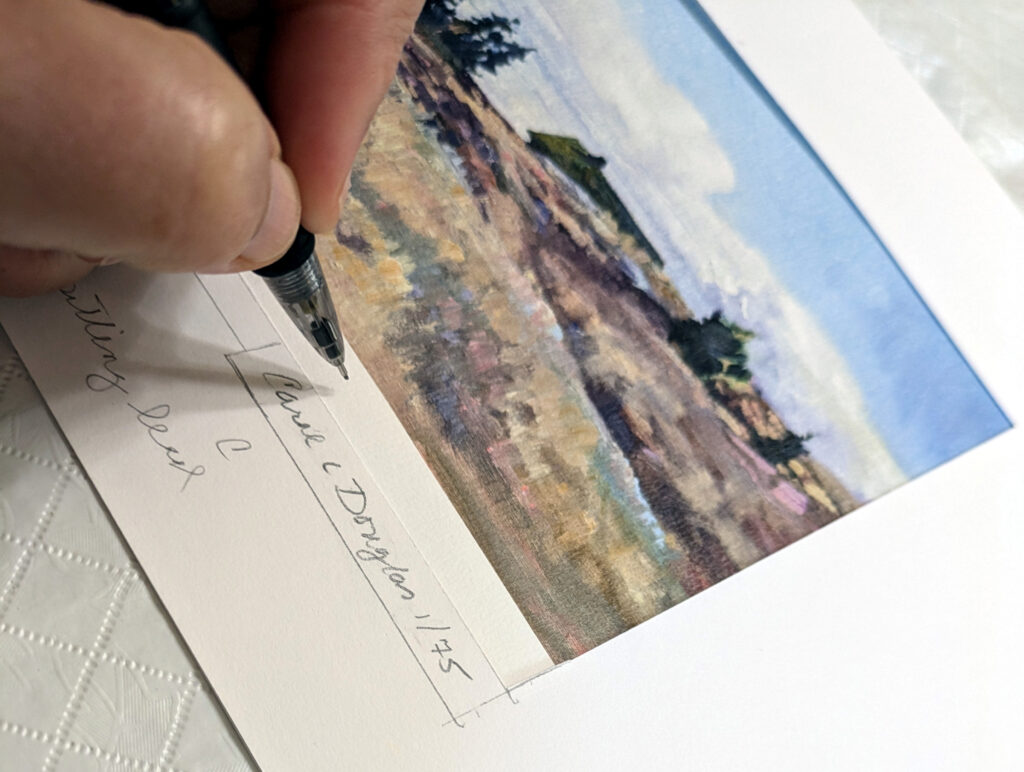

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.