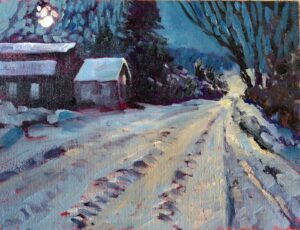

My hometown of Buffalo, NY, is a great place to be from. I often mention it, especially when it’s snowing.

Buffalo is paradoxical: blue-collar and yet elegant, blighted but historic, crime-ridden and yet pastoral. There’s nature everywhere, from the Olmsted-designed parks to the urban prairie that has replaced the immigrant neighborhoods of the 19th and 20th century. (Since my own people came through those streets, I have mixed feelings about this.)

The grain elevator was born in Buffalo. Grain elevators made Buffalo the largest grain-shipping port in the world in just 15 short years. Those elevators also died there, when the opening of the Welland Canal rendered grain cross-docking obsolete. Finding an adaptive reuse for these buildings has been a chronic challenge. It’s like keeping Grandma’s giant harmonium in your living room—historically important, but taking up a lot of space that could have had more practical use.

My home city spent the second half of the twentieth century on its uppers. That’s when I lived there, so that’s the Buffalo that’s shaped me.

Direct and indirect

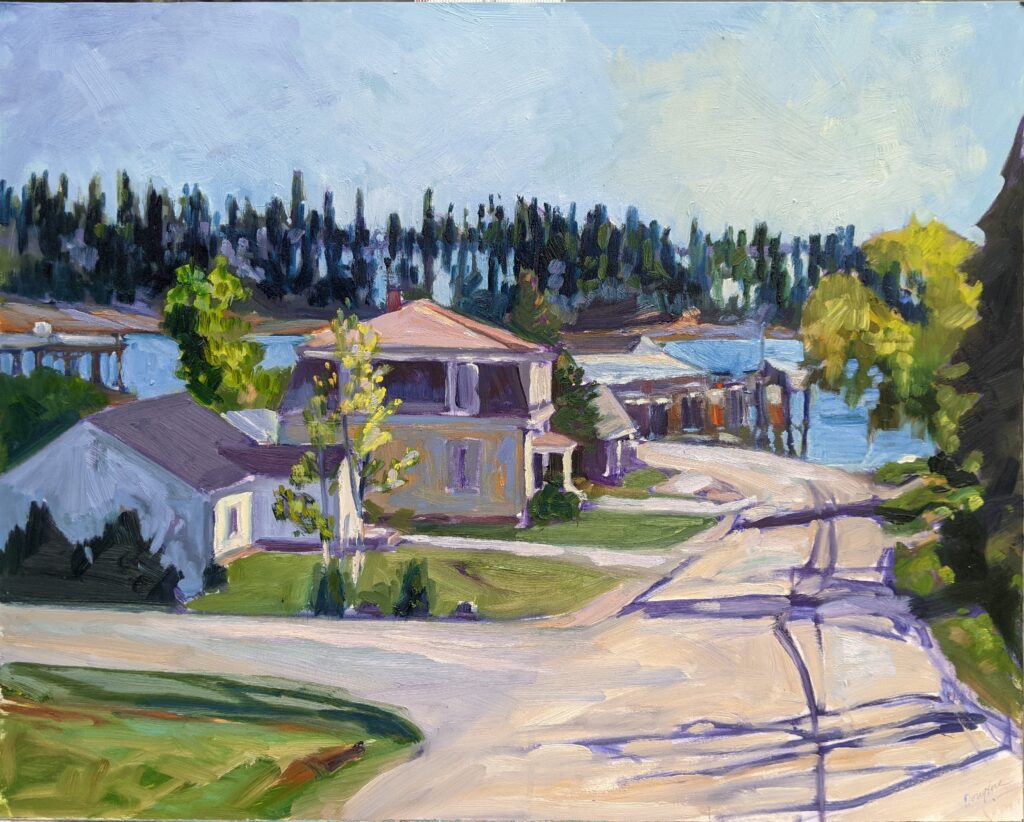

In some ways, that influence was direct, as in the art I saw at the former Albright-Knox Art Museum and the Canadian Group of Seven painters from just over the river. With two Great Lakes in my backyard, I couldn’t help but love all things nautical. In other ways the influences were indirect. My hometown is multicultural, street-smart, feisty and frugal. I am too.

Inevitably, there were also negative influences. After fifty years of economic contraction, there was an expectation of failure; that’s one big reason the Bills have always been so beloved. There were strong cultural, religious, and familial expectations that kept people in place. We left because there were no jobs, but I would probably never have become a professional painter had I stayed.

I live on the Maine coast now, where there are many professional artists. As we all know, iron sharpens iron. The color is clearer and brighter, the light is sublime, but, alas, there’s little cultural diversity. Maine is the whitest state in the nation.

What are the cultural expectations of the place you currently live? The place you’re from? How are they expressed in your work?

Interpretation

Of course, everything I wrote above is my interpretation. I have friends and family who would loudly disagree with my characterization, if they read this blog.

Personal connection

I’ve never found it difficult to paint grain elevators or urban clutter. They’re part of my cultural heritage. I can paint my own kids and grandkids; they’re unalloyed joy. But I started a painting last year, as yet unfinished, that I thought would be a sentimental look at my childhood. Instead, it dredged up some difficult, long-suppressed memories. That’s probably why it isn’t finished.

Have you ever been ambushed by a painting? Have you been able to work your visceral response into the canvas, or as with me, has it foxed you? To a lesser degree, how do your emotions color the less-fraught things you paint? That’s a question I can’t really answer, so I’m looking for inspiration here.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.