We’re in a long run of beautiful weather here in Maine. Ken DeWaard, Eric Jacobsen, Björn Runquist and I have been out plein air painting as much as possible. I really need to do some paperwork, but there’s no rain on the forecast. How do people in southern California get anything done?

Here in New England, we know that any long stretch of warm, sunny, rain-free weather is the exception. Like squirrels storing up nuts for winter, we’re storing up visual memories of these warm days.

I haven’t concerned myself with results. I’ve just painted fast and immersed myself in the process. Are any of these finished? Absolutely not. But they’re better than what was on those boards before.

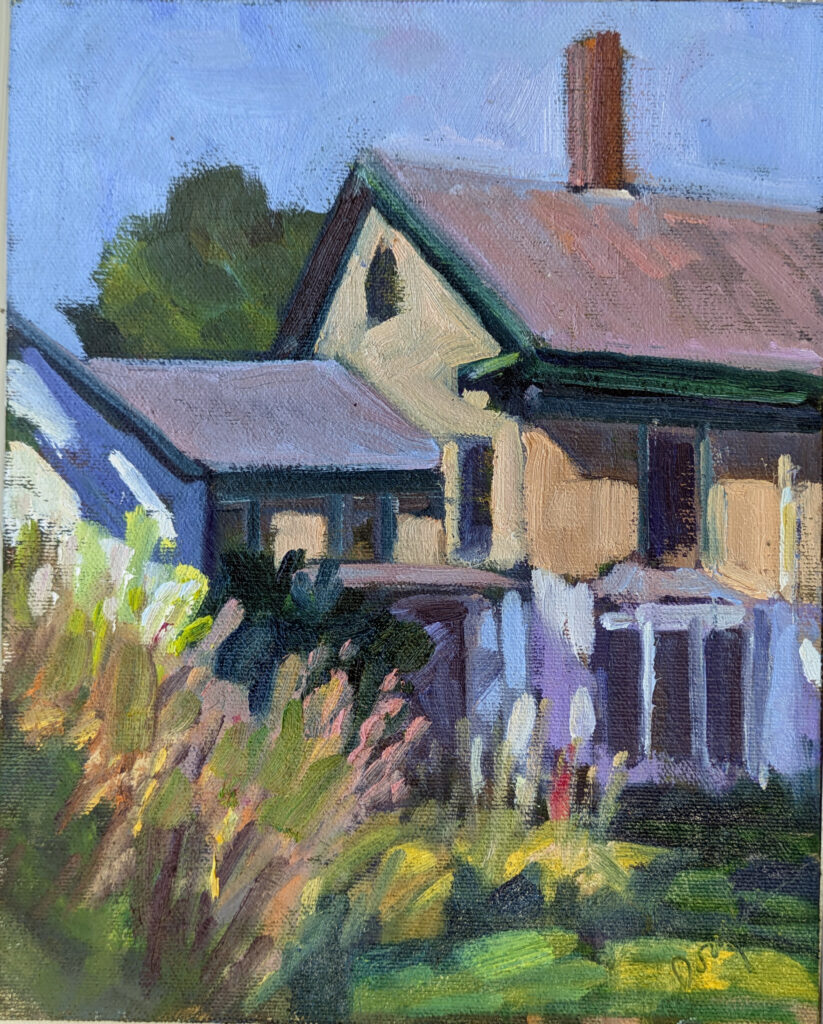

For some reason, it’s been all about the weeds for me this week. I’m a big fan of God-as-gardener; I don’t think artificial gardens can touch wild meadows for beauty.

Nature’s palette shifts as the season progresses. Spring starts with delicate pastel blossoms blooming alongside the lilacs and dog roses. By midsummer, the blossoms grow more colorful, with crown vetch, clover and fireweed (and the brief, glorious burst of red wood lilies). Now that we’re approaching our first frost, we see radiant spirals of white and purple asters among the goldenrod. All are punctuated with the dried husks of milkweed and other earlier-blooming plants.

Purple loosestrife is, of course, an invasive pest and noxious weed; the experts all tell us that. They suggest pulling the plants before they can set seeds or, if it’s not in a wetland, spraying with an herbicide. (However, it likes its feet damp, so it avoids wholesale chemical slaughter, for the most part.)

It’s been around longer than I have, but its press is so bad that I’ve avoided painting it. However, the color is like nothing else in nature, and it complements goldenrod wonderfully.

The heck with it, I decided. If Eric doesn’t mind that it’s growing in his back field, neither do I. “The bees love it,” Eric told me. And anyways, I’m kind of an invasive species here, myself.

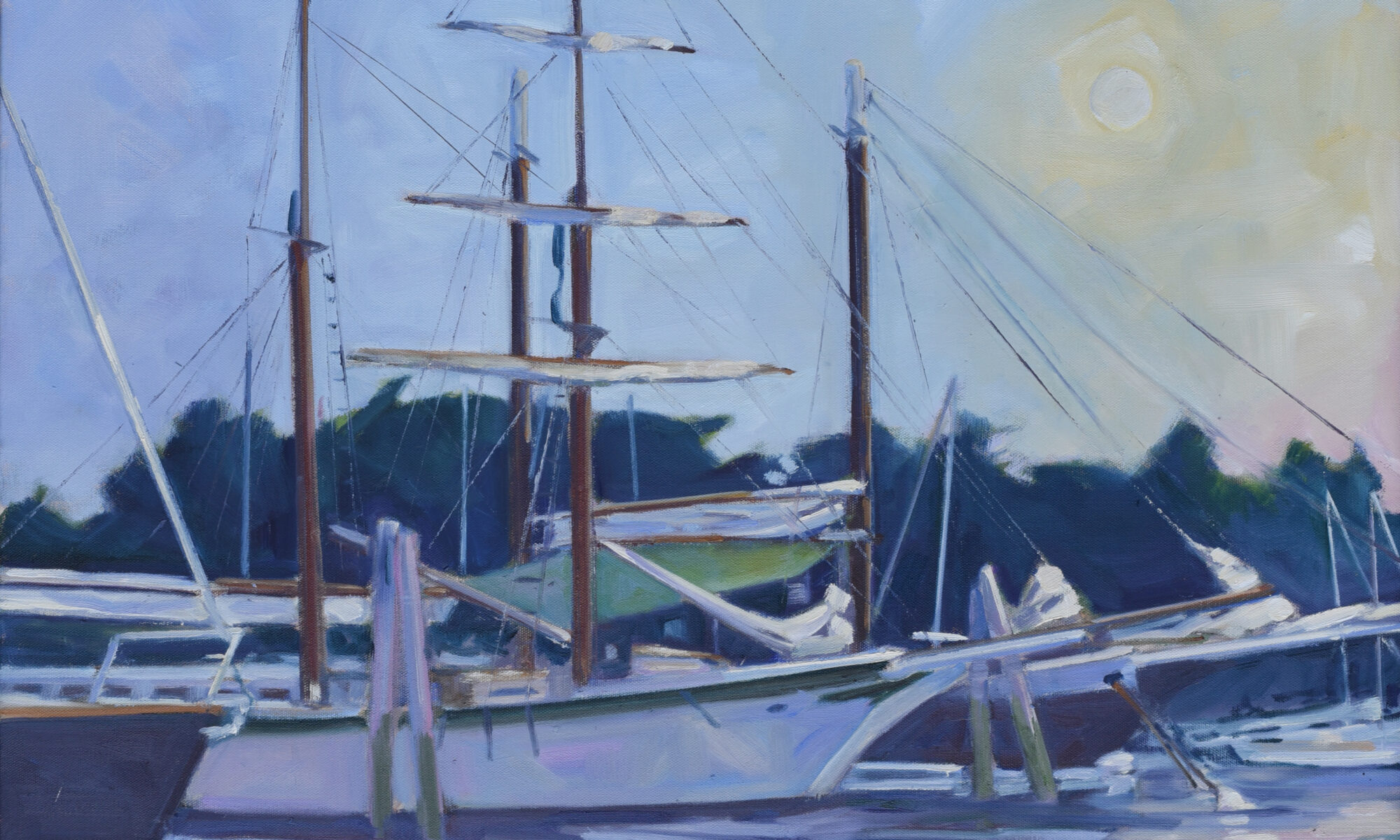

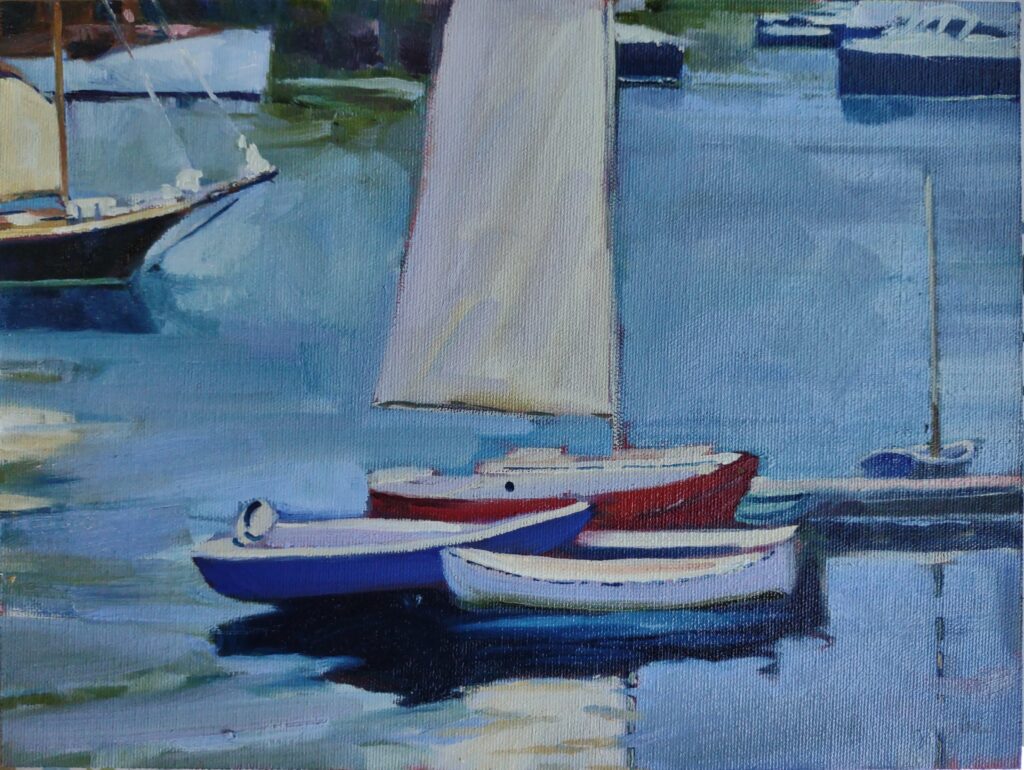

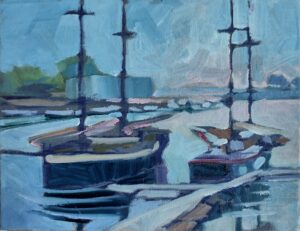

I’ve painted boats at Beauchamp Point many times, since Rockport is a haven for wooden-boat enthusiasts. This week, I was distracted by a group of sunbathers, laughing and talking in the sweet evening air. There’s no sand on this ‘beach’, just rocks and bigger rocks, but there’s something satisfying about stretching out on a sun-kissed boulder. Pro tip: if you want people to leave, just start painting them.

Yesterday afternoon, Björn and I were finishing up, the others having moved along. An onshore breeze picked up. The temperature dropped, the leaves showed their undersides; a large flock of gulls pirouetted over our heads. “Where I’m from,” I told Björn, “the leaves turning over means a weather change.” He’d heard that too, but no such weather change is on the forecast.

After a lifetime in western New York, I could predict the weather from the sky, the wind, and even the smell of the air. Even after a decade, I have no such ability in Maine. I once asked Captain John Foss, what signs he looked for to predict a weather change. “I listen to the weather forecast,” he told me.

Mark next Friday on your calendar

Grand opening

Carol L. Douglas Gallery at Richards Hill

Friday, September 13, 5-7 PM

394 Commercial Street, Rockport, ME 04856

For more details, see here.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.