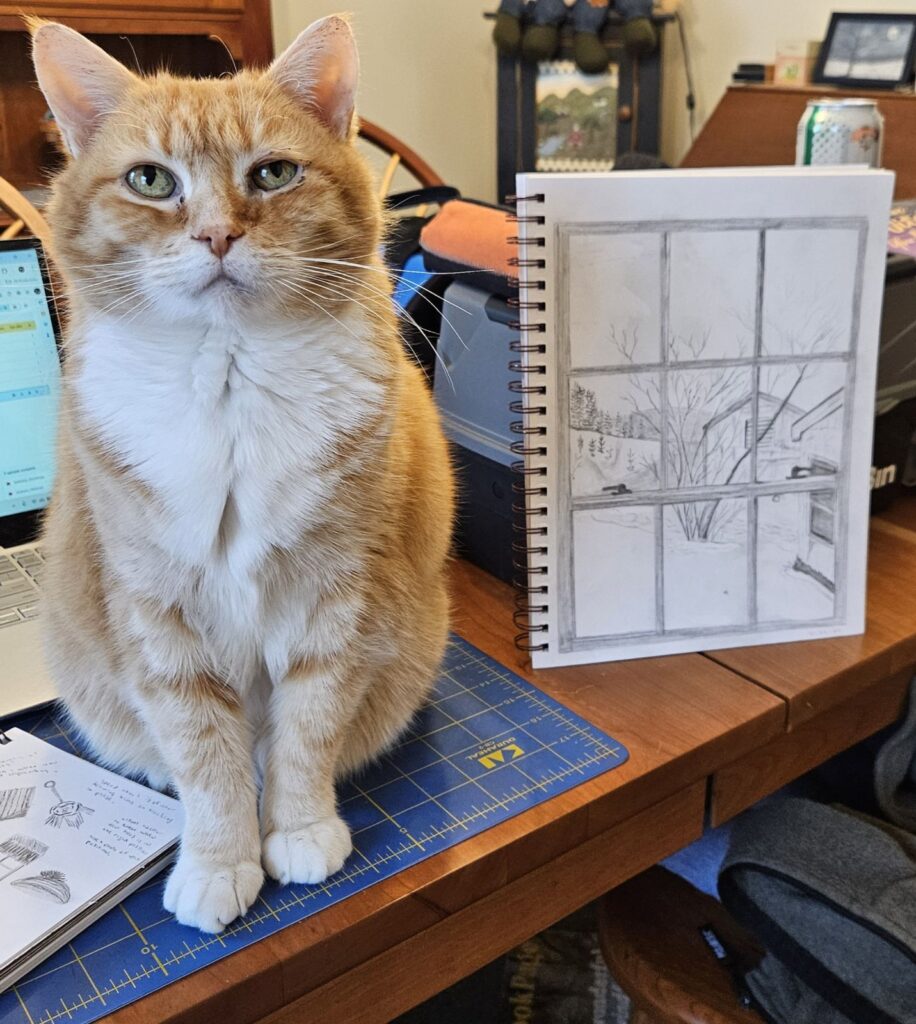

For several years I had a feline student in my zoom classes. Wylie attended faithfully every week, ‘assisting’ his human, Pam Otis, by standing on her drawing board, snaking himself around her monitor, jumping into her lap, and using every other cat trick that assures that work never gets done. I posted so many pictures of Wylie on Facebook that people assumed he lived with me.

After I posted Dogs in art: ten great dog paintings and why I love them, I expected an email from Wylie demanding equal time for cats. Perhaps his silence meant he was already not feeling well, because last week he passed away suddenly and unexpectedly at the age of 16. Wylie, here are the cat portraits you meant to ask for.

Top ten cat portraits

Leonardo da Vinci drew sketches of the Virgin and Child playing with or carrying a cat six times. Either the painting never materialized or it didn’t survive, but it’s clear from this and his other cat drawings that he had a real cat at home. This one is a cat that’s had just about enough, thank you, which in turn humanizes the Infant Jesus.

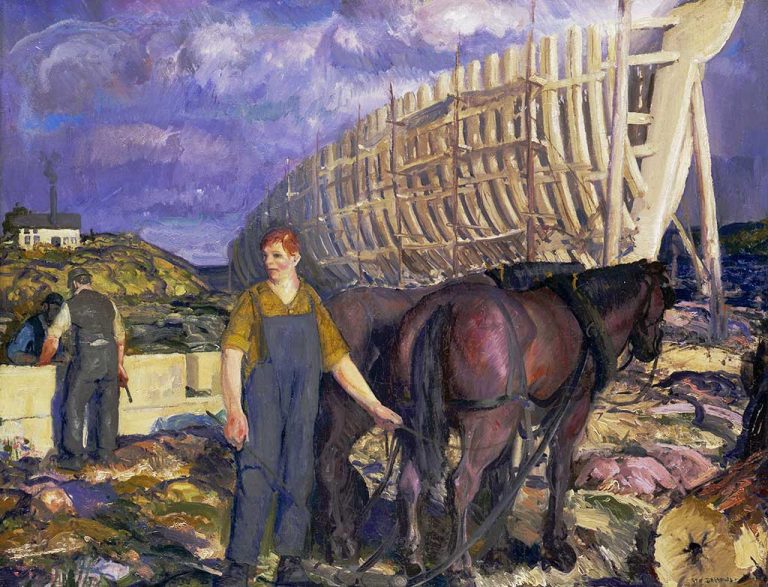

This painting was done just four years after Christina’s World. The model was Christina Olson, the inspiration for the earlier painting. She was the victim of a wasting disease, although its exact character is unknown. Much of how we perceive our pets is based on our interactions with them. This is a moment of tenderness to which anyone can relate.

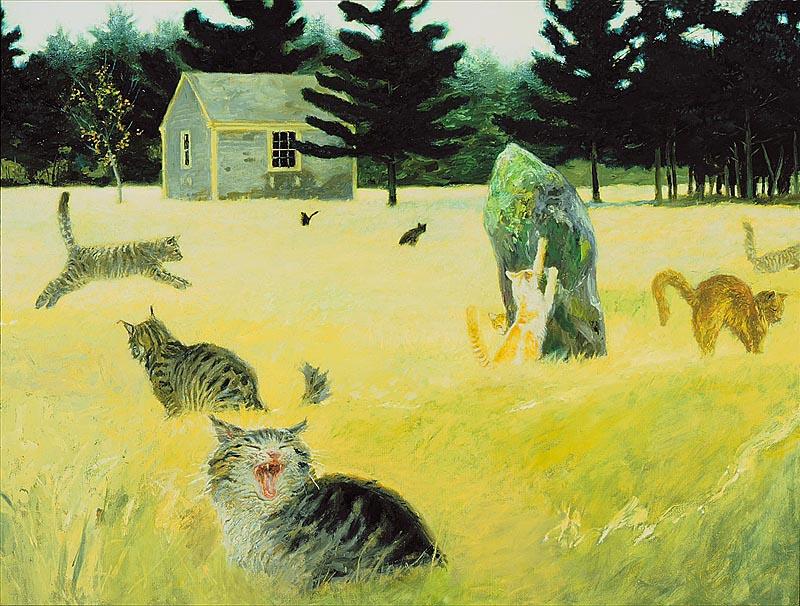

Then there’s Jamie Wyeth, whose relationship with animals is more astringent and far funnier. I have known many Maine Coon Cats and think of them as overlarge house cats mainly interested in their baskets. The idea of them caterwauling in unison in the tall grass strikes me as very funny indeed.

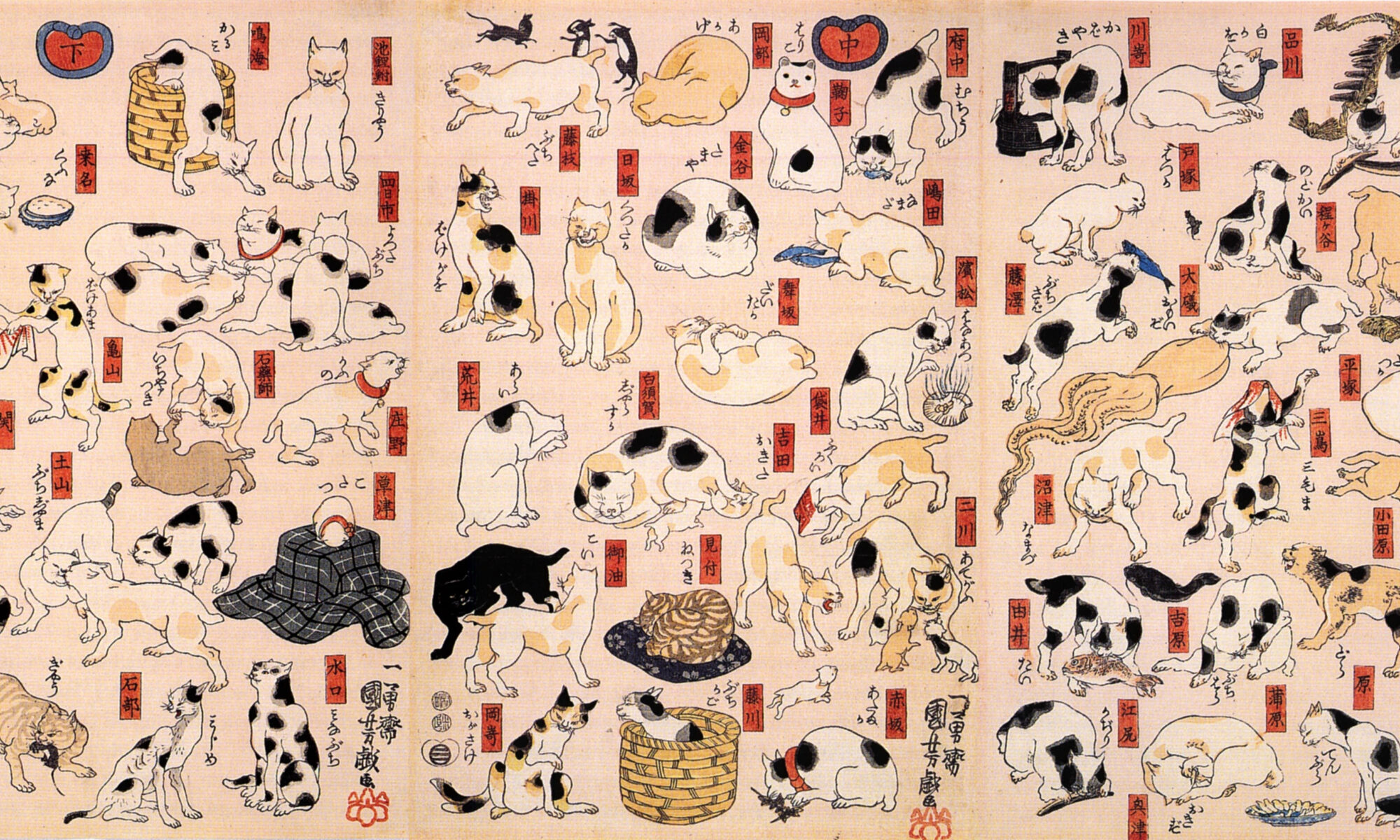

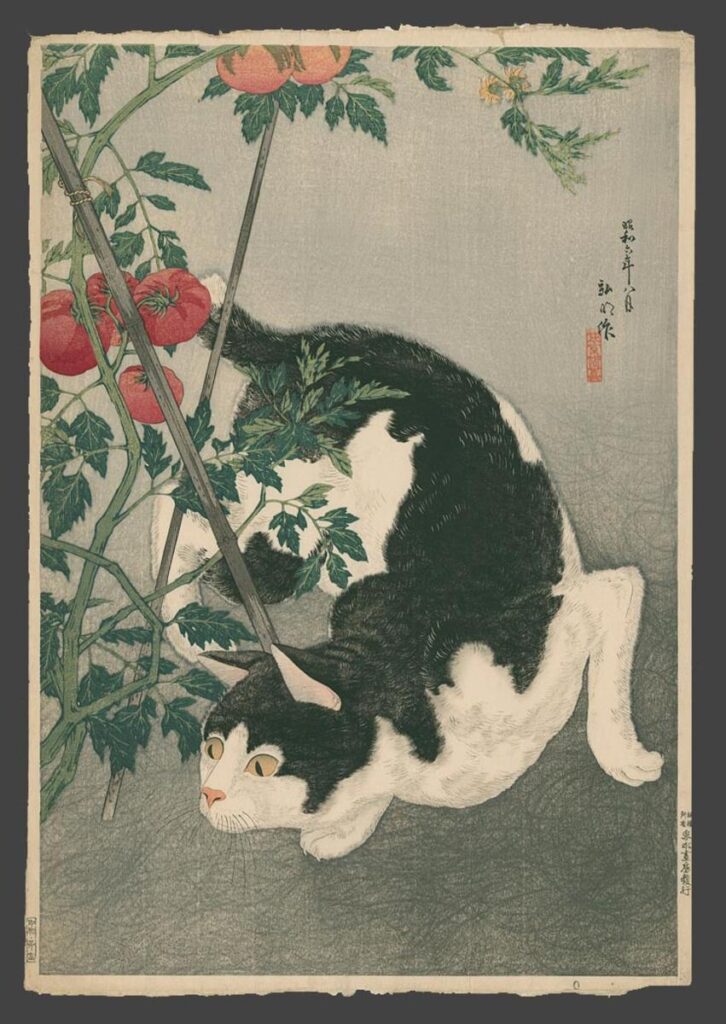

Cats have been an important motif in Chinese, Japanese and Korean art for centuries. They have a symbolic meaning that’s missing for westerners, representing good luck, prosperity, protection from evil, and longevity. Part of that has to do with their skill at eradicating pests. Here we have a shrewdly-observed cat’s eye view of hunting.

Many artists, including me, have a hard time liking Renoir. This painting differs from much of his work in that it’s a real girl with a real cat. That cuts through his “syrupy, falsified take on reality,” as critic Sebastian Smee described Renoir’s oeuvre. That’s a happy but very real cat.

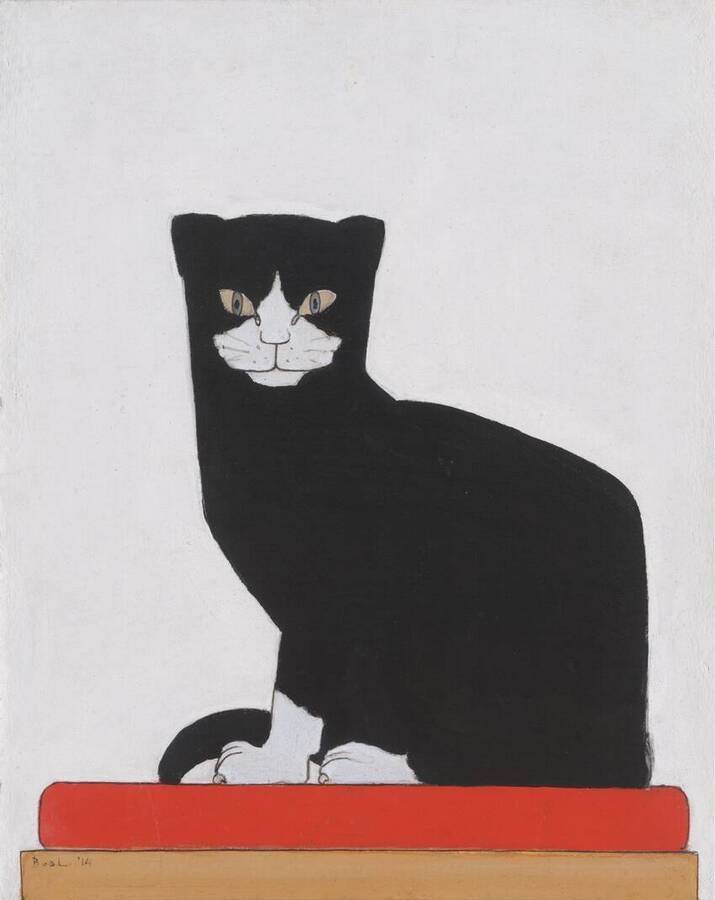

Bart van der Leck’s principal fame to claim is as a cofounder of De Stijl with Piet Mondrian et al. That said, he ultimately backed off pure abstraction to being satisfied with simplifying representational forms. This cat would be just another clever motif if not for that knowing face.

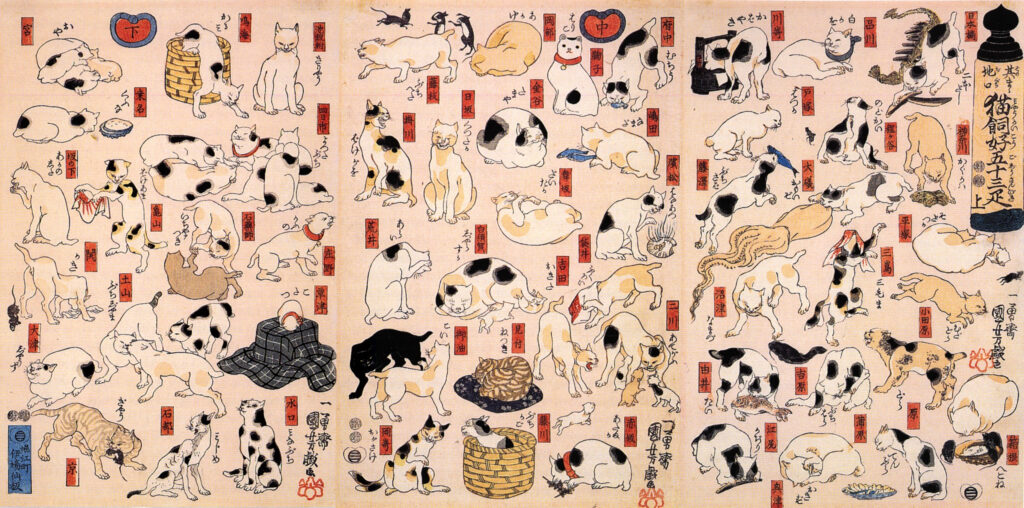

The Tōkaidō road linked the shōgun‘s capital, Edo, to the imperial capital, Kyōto, making it the most important road of old Japan. The ‘stations’ were its rest stops, and they were a popular subject for prints. You could probably get a nice fat thesis paper out of comparing this with Utagawa Hiroshige’s far-more-literal Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō. Or, how would you represent the rest stops on I-90 as cats?

The star of this painting isn’t the light-grey kitten, which you can barely see cradled in the middle boy’s arms. It’s not even the three youngsters, raptly attentive to their pet. It’s Mama Cat, sitting up so proudly to the left.

Dame Elizabeth Blackadder was the first woman to be elected to both the Royal Scottish Academy and the Royal Academy of Arts. She did so while embracing ‘feminine’ subjects like cats and flowers. She lived a long, happy, productive life, and her cats (for which she’s well-known) are fat, sleek, and content creatures.

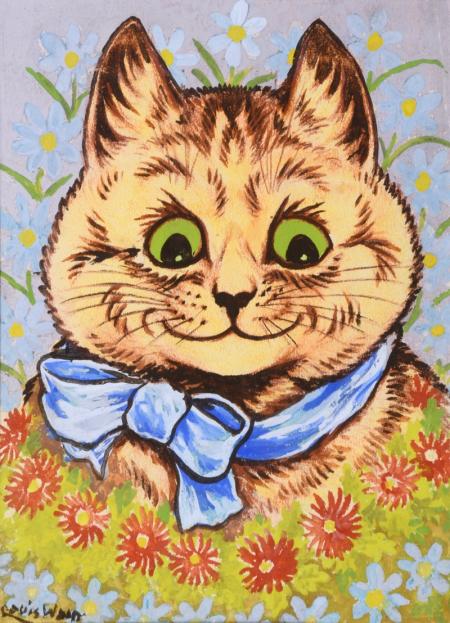

Louis Wain was another famous painter of cats, but his story isn’t nearly as happy. His early cat paintings are precious and anthropomorphic. “English cats that do not look and live like Louis Wain cats are ashamed of themselves,” said H. G. Wells. In 1914, he suffered a severe head injury and was eventually certified insane. I tried to find an example of his work that bridges the work of his younger years and the more troubling work he did post-brain injury.

If you still want more cats in art, check out these cats who walked across manuscripts hundreds of years ago.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

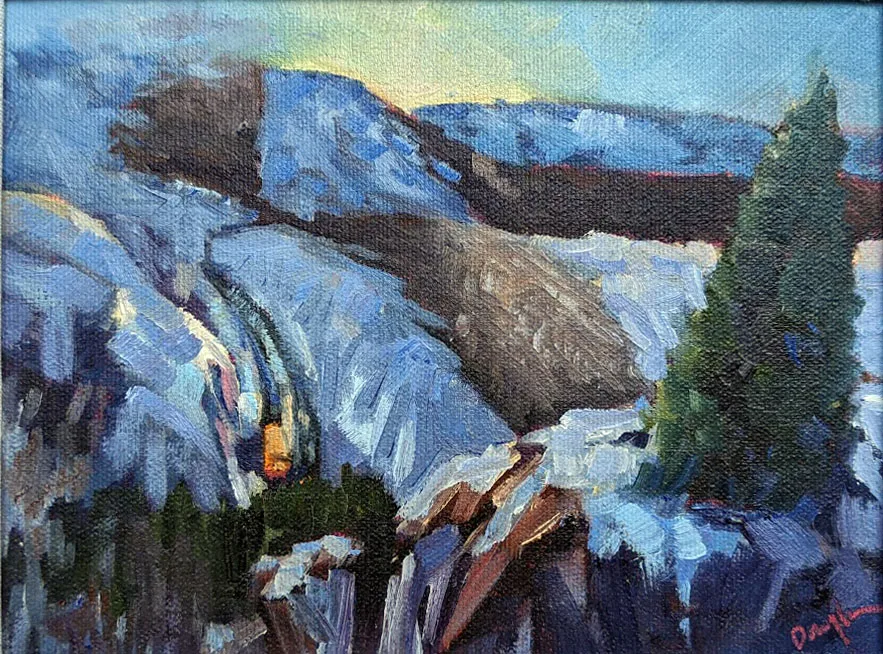

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.