One of the questions we are often asked at plein air painting events is, “Did you really finish that whole painting in one day?” The answer, of course, is yes—or sometimes two or three paintings. We have trained ourselves to be fast, but that didn’t happen by painting large set pieces. It’s by churning out small studies.

My buddy Bobbi Heath recently wrote an excellent post on how to do ten-minute daily exercises in paint. It’s complete and I have little to add, except the rationale for why lots of little paintings will get you to your stylistic goal long before a few major set pieces.

Art & Fear: Observations on the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking, by David Bayles and Ted Orland, is a book I frequently recommend. I’m up in Schoodic and can’t access my copy, so this will be a very loose interpretation of what they actually wrote. They described an art class where the students were divided into two groups—the first would be graded on quality, the second on quantity. It was the students pushed to produce lots of work who, in fact, made the best work. That is because talent, in the end, is really about perseverance and hard work. The artist must paint a lot of duds before he or she creates something that is truly brilliant.

But these duds do not have to be large, serious paintings—a fact I wish I’d realized much earlier, before I cluttered up my studio with so many big canvases. Often, painting students have lovely photos they took on vacation, or of the perfect sunset, and they want to immortalize them in paint. That’s a laudable goal in its own right, but it won’t actually make you a better painter. In fact, their emotional investment in the content might get in the way of pure painting success. Far better to grab a few objects from around the house and paint them, or paint the view out your front window.

There’s much to be said for the humble still life. Eric Jacobsen is a wicked good expressionist painter, and he often paints still lives—the busier, the better. I’m not a still-life painter myself; I strongly prefer fresh air. But I do live in the north, where winter can make for unpleasant painting. During a blizzard, the best way I know to stay fresh is to set up a still life in the studio and hack away at it.

That’s why so many of my Zoom classes are based on still life. I understand when students say, “I hate still life,” and that they’d rather paint landscape or portrait. However, they won’t learn half as much from copying a photo as they will learn from painting from life. Still life—as Bobbi Heath says—is the next best thing to painting plein air, in terms of training and growth.

To be honest, I never get my oil paints out for a ten-minute exercise. I’ll paint an apple in gouache or watercolor; the clean-up is easier. (Switching between media teaches you new ways of applying paint, and different ways of looking at things. However, for a beginner, it can be confusing.)

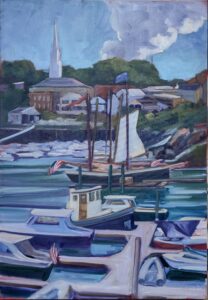

I have my own interpretation of fast warm-ups; I call them ‘practicing my scales’ or ‘practicing chip shots.’ They usually involve running down to the harbor to paint a few boats before my gallery opens, but they might also be something as silly as painting a basket of beach toys in my driveway. The important thing is the daily discipline, and it’s something I’m concentrating on right now.

My friend Peter Yesis has done a lot of these fast warm ups over his career—for a long time, they were his daily discipline. They served him in good stead at Camden on Canvas this weekend. Peter’s taken a long hiatus due to serious illness, but he knocked this week’s painting out of the park. The brushwork and paint application were assured; the drawing was perfect.

So, if your goal is to get better, fast, try practicing with small, unassuming paintings. They might just end up being masterpieces.